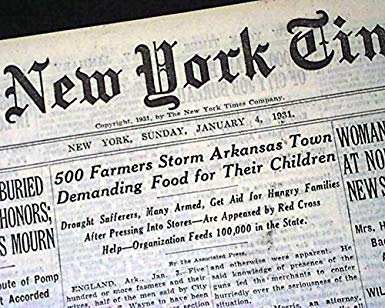

On January 4, 1977, Augustus Hawkins, a congressman from California, introduced what became the Humphrey-Hawkins Act. Let's talk about the fight for full employment and why we still need it today!

This full employment bill initially promised making the government the employer of last resort to ensure basic economic justice for all Americans.

The watering down of this bill by the Carter administration demonstrated both the overwhelming fears about inflation in this era and a consistent lack of leadership by Carter as he governed well to the right of his liberal Congress.

As late as the mid-1970s, liberals believed another era of left-leaning government was around the corner. When Ted Kennedy fought to kill Richard Nixon’s milquetoast national health care plan, it was under the assumption that something much better would come soon.

While the recession and oil shocks that began in 1973 put a damper on this, liberals did not believe the fundamental equation of American politics had changed. They had a lot more they wanted to do. One goal was to move toward full employment.

The Full Employment Act of 1946 had been a compromise measure signed by Harry Truman that created the principle of this at the federal level but did little to achieve it. But private employers took care of most of this problem over the next 25 years.

By the early 1970s, with the economy slowing, this became more of a concern. And so liberals began planning a bill.

The leaders were Hawkins, a founder of the Congressional Black Caucus who represented the area of Los Angeles that included Watts, an area with severe unemployment that helped lead to the 1965 riots and....

Minnesota senator Hubert Humphrey, the 1968 Democratic presidential nominee and possibly the best friend the AFL-CIO has ever had in Washington.

Humphrey, Hawkins, and their allies hoped that a full employment bill would solidify the status of American labor by undermining the racial, gendered, and regional differences that created different wages and capital mobility.

Unions hoped it would be a new Wagner Act that would allow it to organize the South, which it had notoriously failed to do after World War II.

By 1974, they came up with a plan that would not only establish the principle of full employment with the federal government as the employer of last resort, it would also give citizens who felt deprived of work the right to sue the government.

The president would have to submit an annual plan to Congress to achieve full employment (defined at 3 percent unemployment) and local committees would exist to coordinate job needs in their communities.

The private sector would ideally hire people, but a big new program of government jobs would be created too.

Effectively, this was an attempt to unite the Black, Latino, and white working classes to create a social democratic America in the aftermath of the riots and tensions of the previous decade.

Liberals hoped to introduce Humphrey-Hawkins in 1976.

But it could not proceed without support from the AFL-CIO and, typically concerned more about its own agenda that workers as a whole, the unions demanded concessions that included limiting it to adults and removing the clause allowing suing the government.

More importantly, because labor would not support federal wage and price controls, that got stripped too. That made unions happy but not the nation’s economic establishment and politicians worried more about consumers than labor.

This opened the bill up to attacks from those concerned it would cause massive inflation.

Unions should have seen through this, but again, the Meany and Kirkland years saw unions a lot more concerned about their particular members’ earning power than broad-based working class welfare programs.

With Congressional Democrats unsure about the bill, it got pulled for 1976, with the plan to reintroduce it when Democrats took the Oval Office that fall.

Liberals hoped Jimmy Carter would be the new FDR or LBJ. But this was a delusion. Carter was always a moderate and, hailing from Georgia, owed very little to unions.

And while that was true of Johnson as well, LBJ at least had an active history of working for the poor while in Congress.

Carter did not. Carter did not trust this bill from the very beginning and it only got worse as he began surrounding himself with neoliberal advisers worried more about inflation than employment.

And while I don’t mean to trivialize the high inflation in the 70s four decades later, it’s clear the emphasis on the issue as the overarching goal of economic policy that still dominates today has severely limited our national imagination to create new social programs.

By the spring of 1977, Carter and his advisors already believed that, as written, Humphrey-Hawkins was untenable and ill-advised, despite some weak campaign commitments to supporting it. When labor and liberals attempted to cash their chips, Carter blew them off.

Carter’s chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers Charles Schultze took the lead in defanging the bill. With no bill, Carter would have burned serious bridges with black leaders and that was a political problem.

So Schultze worked for a bill that could have Carter’s support. That would be a bill completely devoid of meaningful provisions. This would allow Carter to say he supported full employment, siphon off discontent, and keep fighting inflation as the number one economic priority.

He was quite successful in doing this. Desperate to get anything passed by late 1977, both Humphrey and Hawkins agreed to all Schultze’s demands.

When Humphrey died in early 1978, the bill became a memorial to him, but that did not lead renewed vigor in its language.

Even so, Carter barely supported it, leading to tremendous frustration with him from both organized labor and from the Congressional Black Caucus, with John Conyers walking out of a meeting with Carter about it in anger.

The final version of Humphrey-Hawkins was a mere shell of its original intent. It had the nation strive toward full employment but with no requirement to do anything about it.

Balancing the budget was as central a goal as full employment, undermining the deficit spending required to make this work.

Concern about inflation ruled the day, and the law set inflation goals for the government that included 0% by 1988, an overreaction that could lead to deflation were it actually achieved.

The evisceration of Humphrey-Hawkins coincided with the rise of conservatism and the war on organized labor that would kick into high gear with Reagan taking power in 1981. This was the last chance we had for meaningful full employment legislation.

The failure of Humphrey-Hawkins was a huge missed opportunity, one that we need more than ever with the rise of automation and the continued impacts of deindustrialization destabilizing the working class.

If we are moving into an age of no employment for many workers, as robotics creates an era where automation is replacing industrial labor rather than ushering in a period where new jobs are created in different forms of manufacturing, a federally guaranteed job is the best answer

It’s possible that we will look at the original drafts of Humphrey-Hawkins as a model. Certainly I already do.

I wrote up an op-ed for the New York Times that argued this in 2018. For me, this makes more sense than UBI, though of course just giving people money has its upside too.

nytimes.com/2018/04/25/opi…

nytimes.com/2018/04/25/opi…

My own position on these debates is that work is a centerpiece of human life and that's always going to exist. We can think about other forms of work, sure. But the idea that we can just say "we need to deemphasize work" is completely utopian. And I'm not a utopian thinker.

The other thing I'll say here is that we are entering a big wave of Carter nostalgia. And look, Carter's a good person. But he was a bad president and it does not help us to handwave that away because he's not Donald Trump and has good musical taste.

I borrowed from Jefferson Cowie’s outstanding Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class, in the writing of this thread.

Back tomorrow to discuss Henry Ford's $5 day and how actually terrible he was to workers and how that's not something we should be talking about in a positive way.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh