This remarkable embroidered tent from 19th-century Iran, now in the Cleveland Museum of Art, has been popping up on social media quite a bit over the last few days, so I thought I'd do a thread on it to brighten the twitter feeds this weekend...

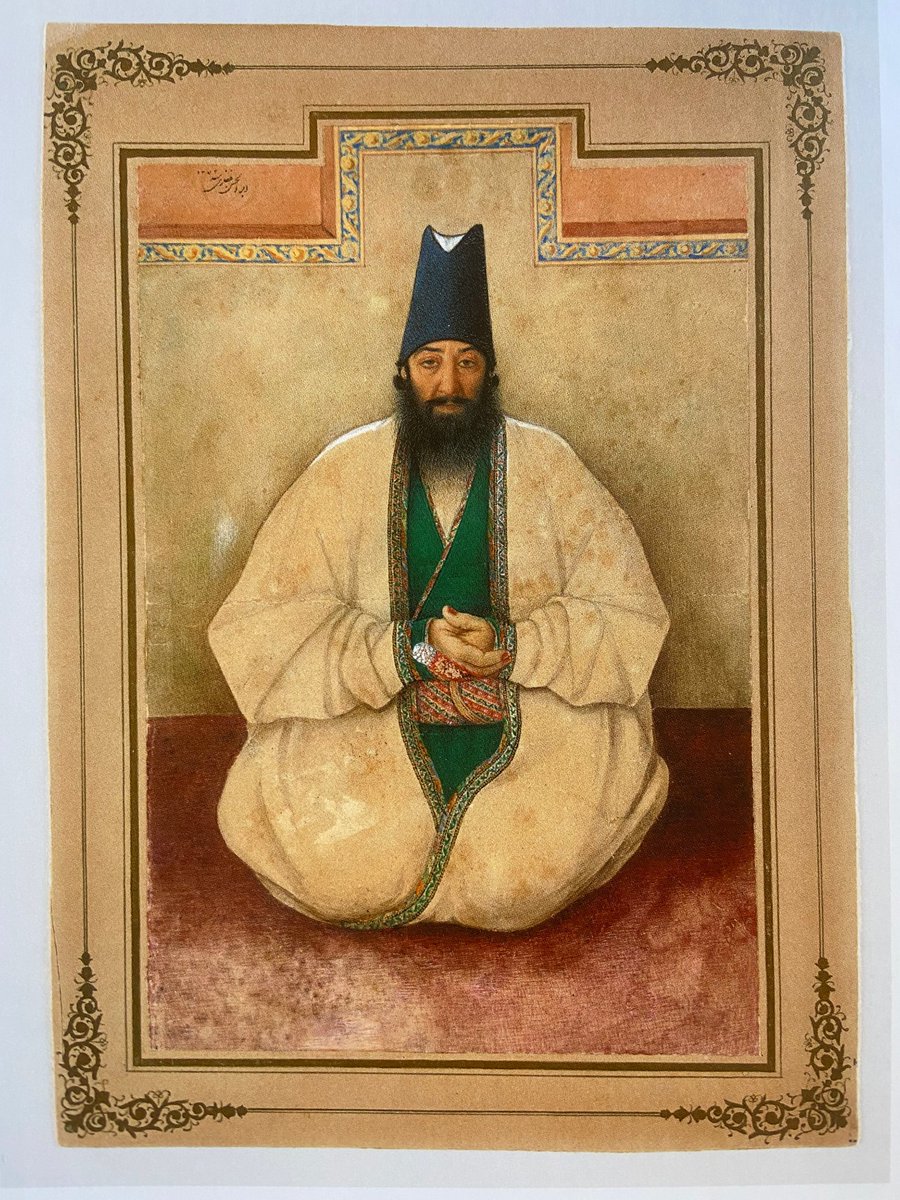

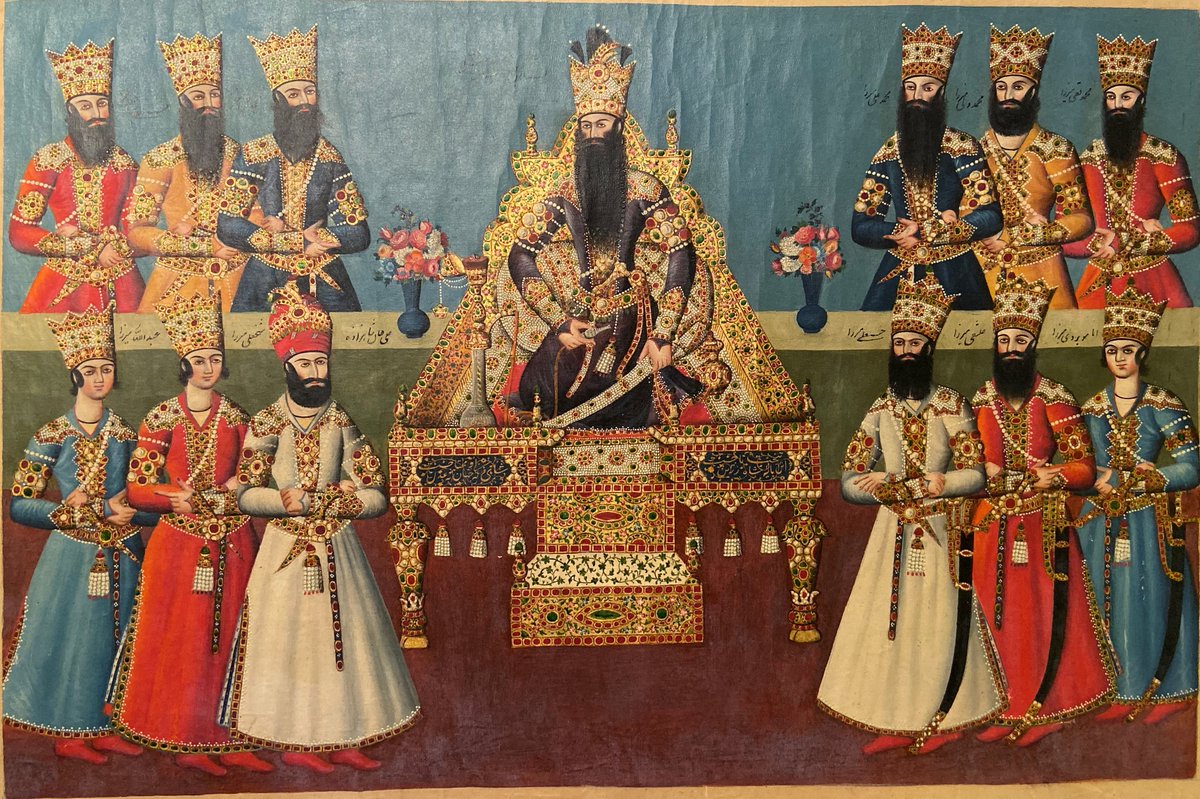

It was made for Muhammad Shah, the second ruler of Iran's Qajar dynasty, who reigned from the death of his grandfather, Fath-ʿAli Shah, in 1834, until his own death in 1848.

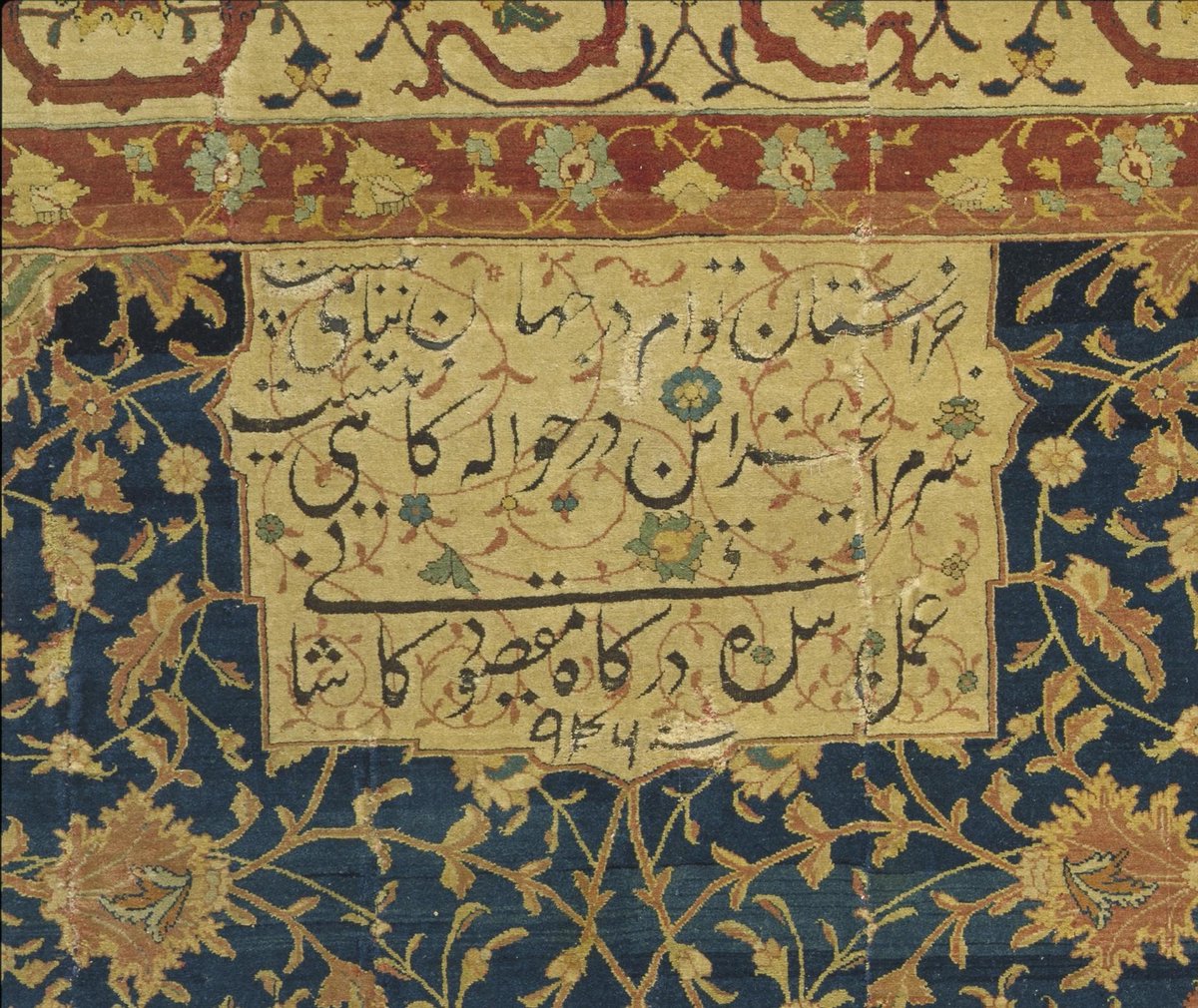

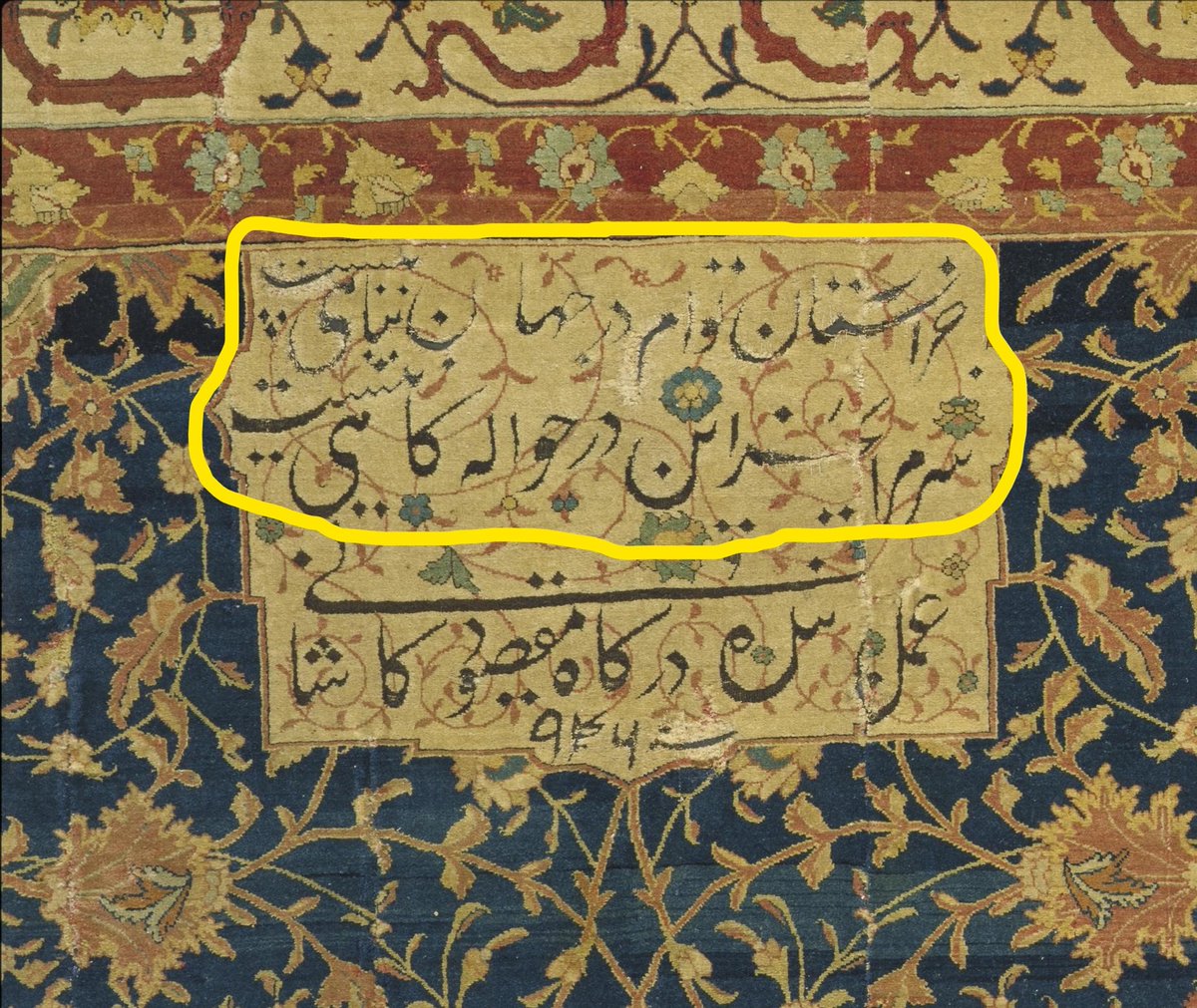

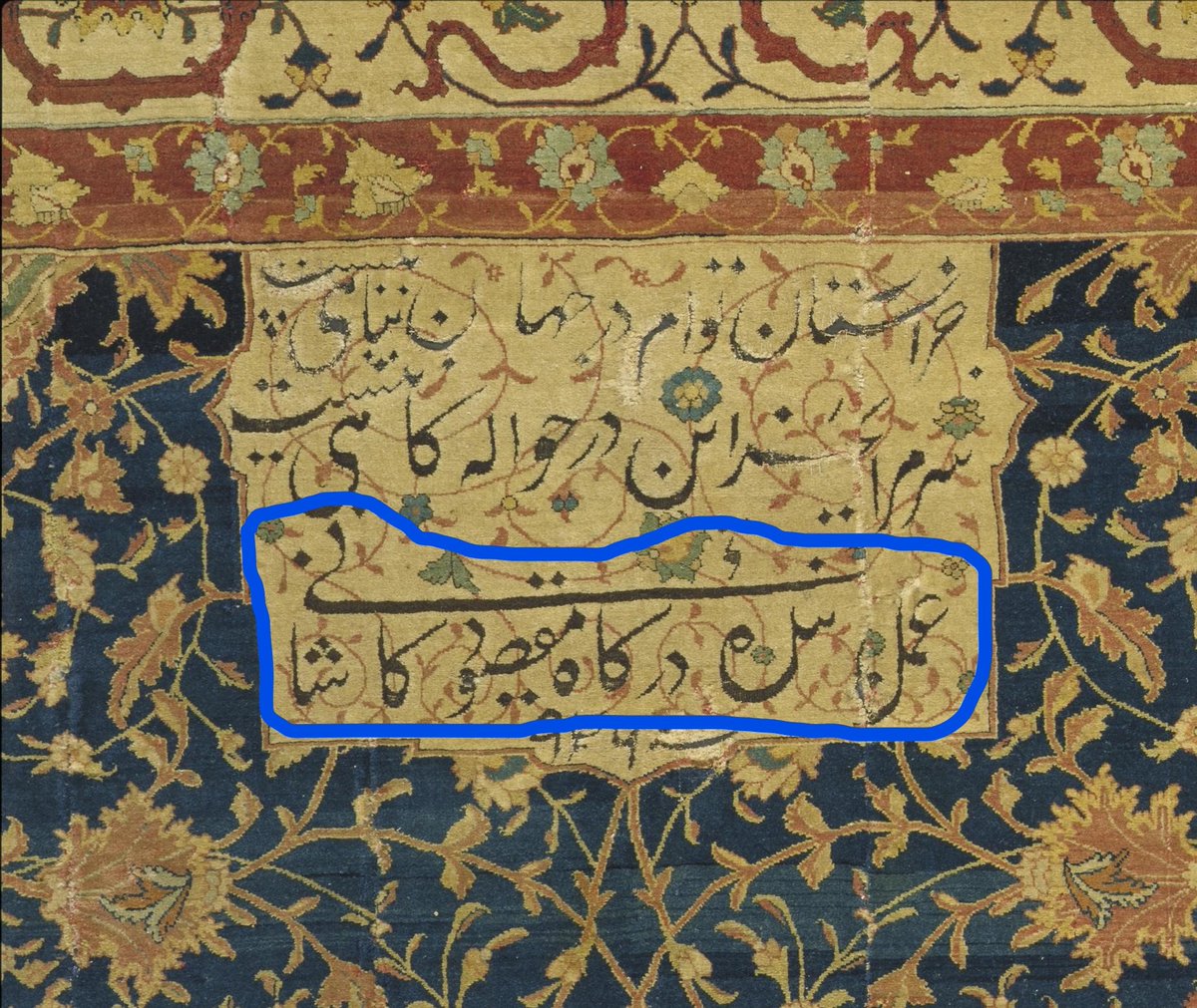

We know it was made for Muhammad Shah as it bears his name, with the title 'Sultan-i Ghazi'. It also has a second inscription, which has been interpreted in a number of ways, but is likely to give the name of the maker, Fath-ʿAli.

The technique is known as rashti-duzi (Rasht embroidery), named for the city in the NW of Iran where is it used. Rashti-duzi most often consists of chainstitch in silk, done with a hooked needle, and applique, on (often felted or fulled) wool. Details from two V&A pieces here:

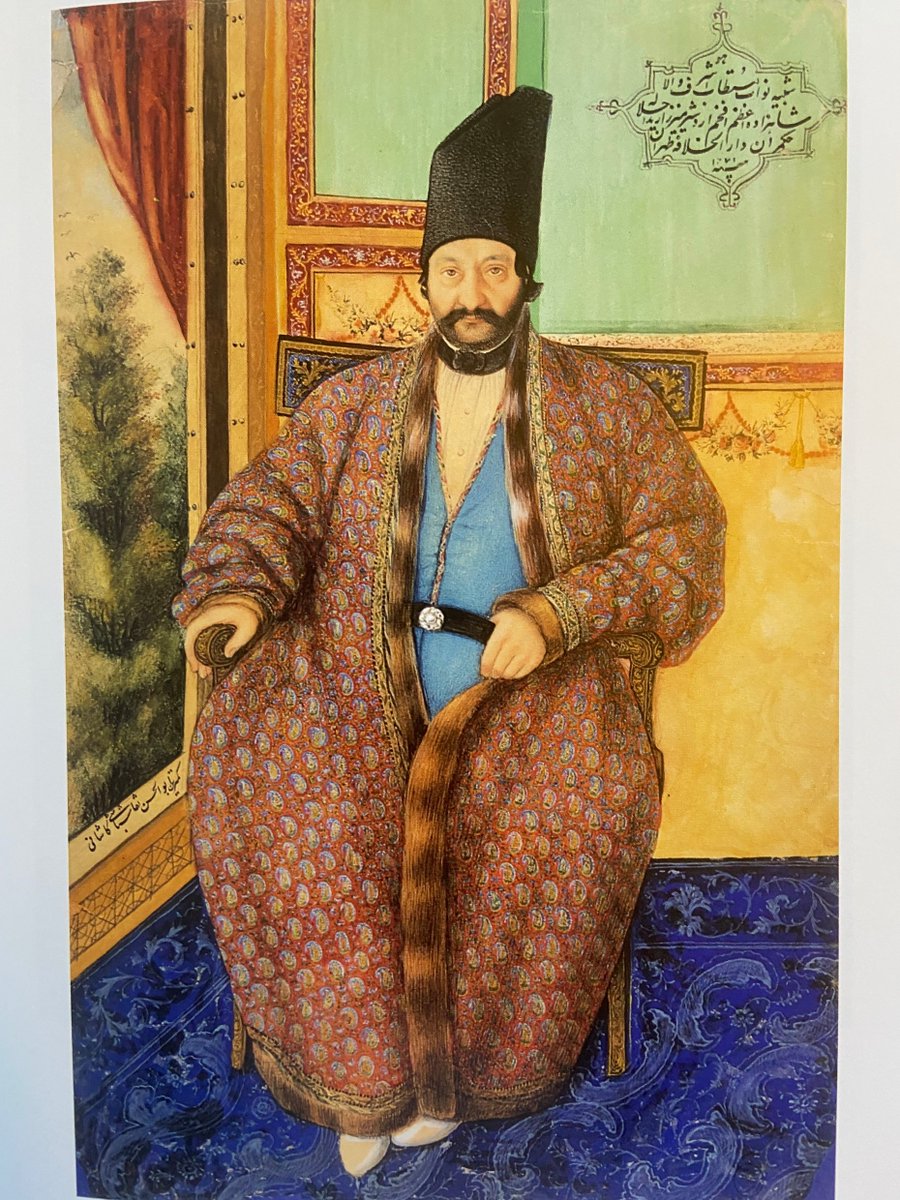

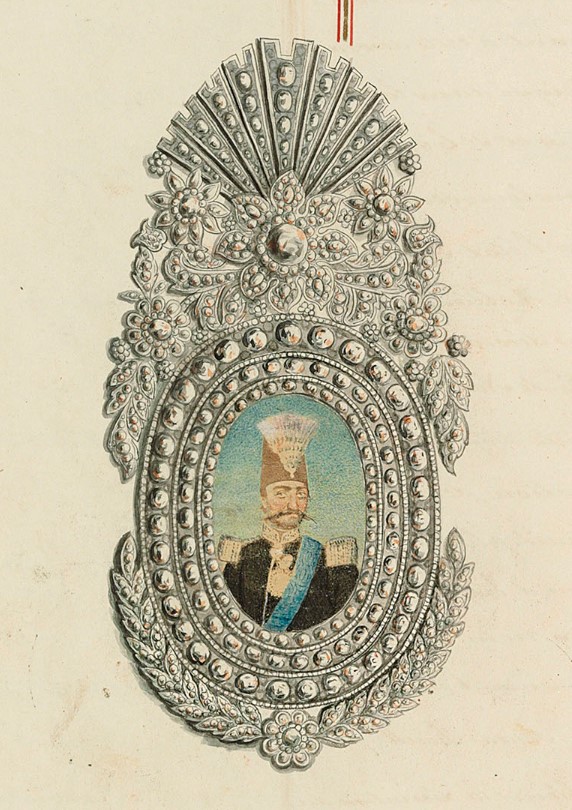

It was not only tents that were made using the technique, but all sorts of items, including saddle cloths & even portraits. The 2nd one here depicts Muhammad Shah's successor, Nasir al-Din Shah, which I photographed when it was on display at Louvre Lens. (The other is V&A).

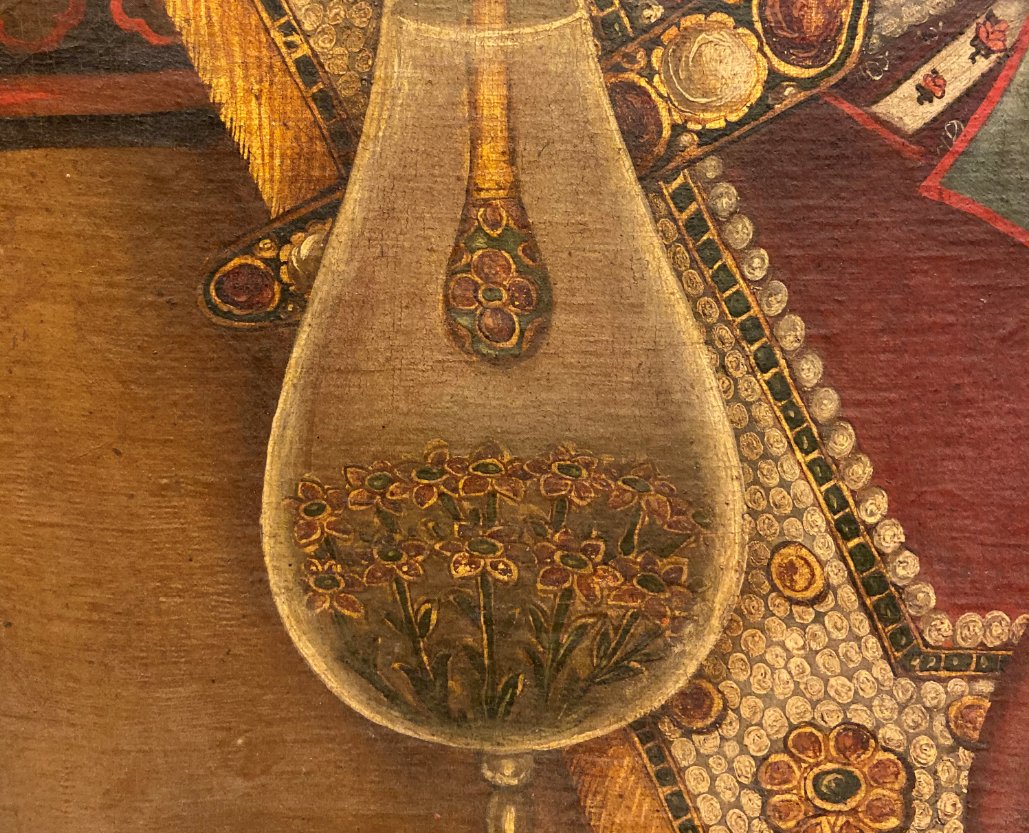

Here's a detail of a rashti-duzi banner, probably for use during Muharram events, which I absolutely love.

The technique must have a longer history, but the earliest existing pieces are likely to be from the 1830s. Later 19th-c. examples show the adoption of European (Russian) motifs. These are details of pieces from the Alpiger collection, recently on display at the Rietberg, Zürich:

While we might now associate embroidery most readily with women, in the 19th century, rashti-duzi was largely produced by men and boys, as seen in this photograph, taken in Rasht.

There are panels which might have formed tents in other museums, such as this one in the Met, but nothing else as complete as the tent in Cleveland, which consists of two large panels, one small panel, and the roof, but is likely to have had more panels to complete the circle.

Here's a video of the tent being conserved and hung:

But how did a royal tent from Iran end up in a museum in North America? Well, that's not entirely clear, as the museum only gives us a partial provenance. Wouldn't it have been great if Sotheby's had demanded more information from Mahboubian!

When the tent was sold at Sotheby's in 1991 it was grouped together with another Qajar tent in the same lot, and the two sold for £66,000. I would love to know where this one is now, but I can't find any clues for the moment.

Edit: Muhammad Shah was the third ruler of the Qajar dynasty, not the second. I'm normally writing about Fath-ʿAli Shah, who really was second and old habits die hard. (Why do I only notice these things after I've clicked tweet!)

An addition of a more complete but less grand example now in the Saint Louis Art Museum:

slam.org/collection/obj…

slam.org/collection/obj…

Also dropping this Enyclopaedia Iranica article on the handicrafts of Gilan here - such a useful resource, it has lots of detail about this type of embroidery and many other things besides:

iranicaonline.org/articles/gilan…

iranicaonline.org/articles/gilan…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh