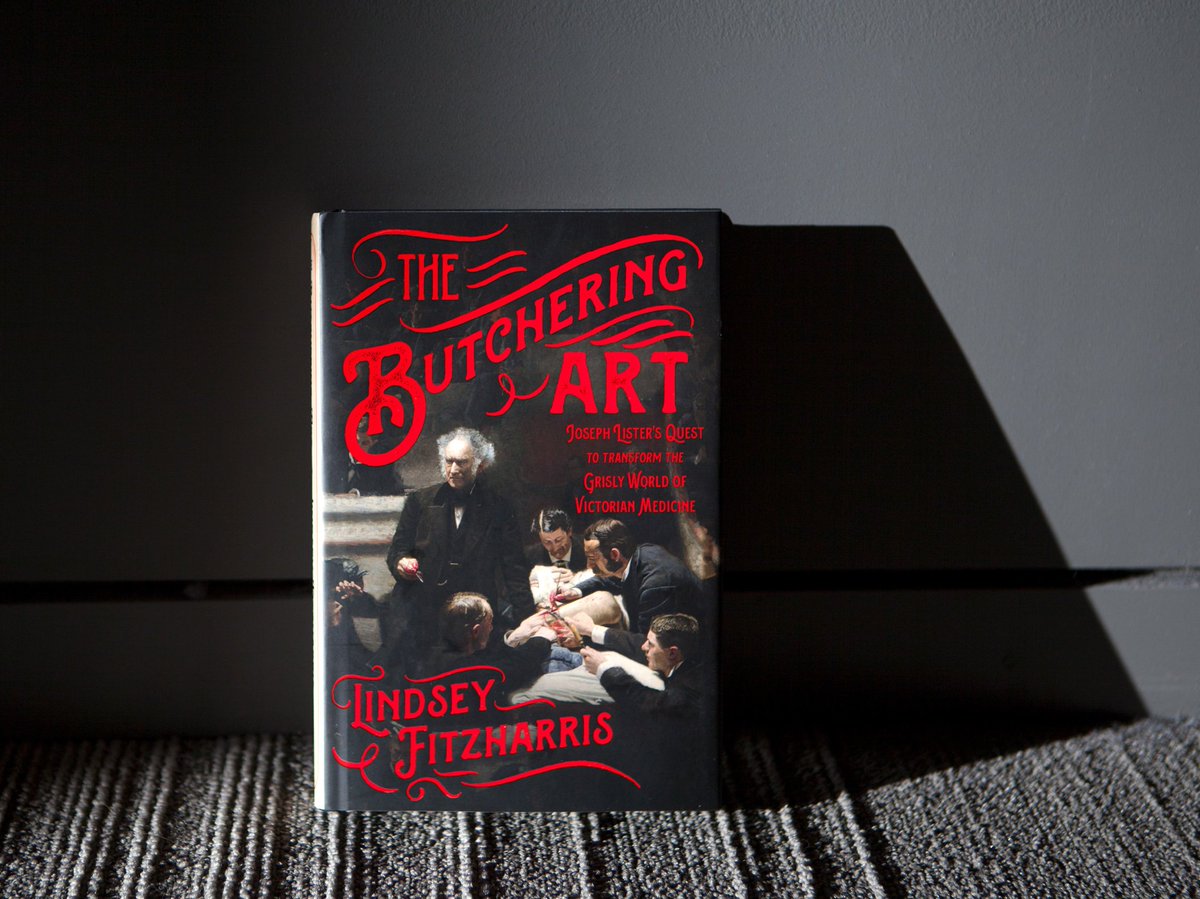

I’ve recently been reading through “The Butchering Art”, a terrific account of 19th century surgery & the introduction of germ theory & anesthesia to Victorian medicine. I highly recommend reading it yourself, but here are some interesting tidbits that caught my attention (1/10)

(2) First, as you can imagine, early surgery was absolutely awful & almost always a last resort. One thing I didn’t realize was that back then, the best surgeons were the *fastest* surgeons — for instance, Robert Liston could remove a leg in less than thirty seconds (!).

(3) Early surgery was limited to “peripheral” conditions, like lacerations & fractures. This is because entering the body in surgery was almost always fatal due to infection. This led to the distinction of physicians practicing “internal medicine”, a term that still persists.

(4) More dangerous than the surgeries were post-operative infections & diseases. Four were particularly common — gangrene, septicemia, pyemia, and erysipelas — & were known as “hospitalism”. With the rise of early anesthesia came a rise in attempted surgeries & hospitalism.

(5) What’s wild about this era, looking back, is that no one really knew what was going on... but their theories made some sense. “Contagionists” thought disease was communicable, being transferred from person to person by “invisible bullets” or chemicals. Not the craziest idea.

(6) “Anti-contagionists” thought the opposite: they thought disease arose spontaneously from filth & was transmitted through poison air (“miasma”). Indeed, many terms like “malaria” come from this perspective = “mala” = bad, “aria” = air. This theory also seems plausible, no?

(7) Of course, the real answer, that disease can spread through tiny, invisible organisms sounds like borderline science fiction. Though some did think disease could be spread through “animalcules” — small organisms — germ theory didn’t receive widespread attention until Pasteur.

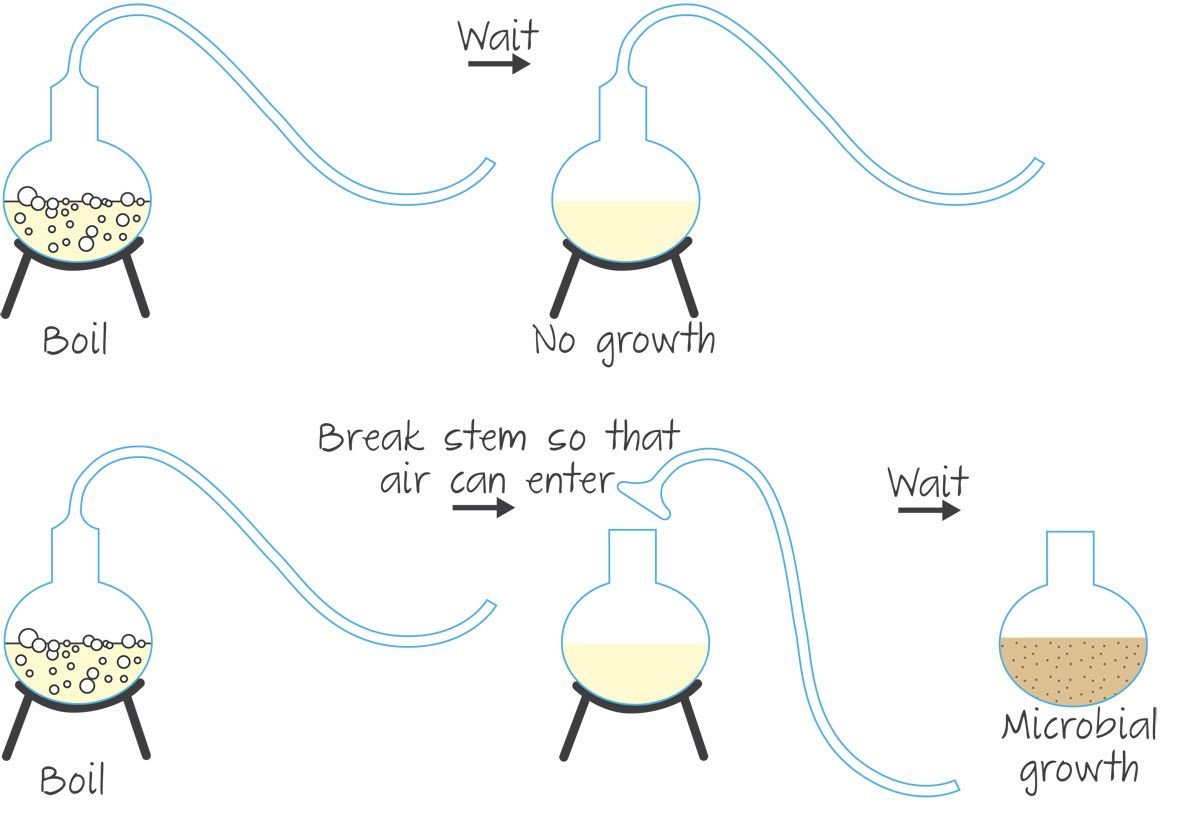

(8) In a cool experiment, Pasteur boiled liquid to kill off microbes, then used 2 flasks: an open-top flask & an S-shaped one that prevented dust from entering. He then showed that the S-shaped flask liquid remained uncontaminated. Microbes came from the air, not from the liquid.

(9) Inspired by Pasteur, Joseph Lister adopted the idea that it wasn’t *air* that caused infections, but rather microbial life *in* the air. He was among the first to suggest pre-treating wounds with antiseptics to prevent infection, as opposed to trying to control it afterward.

(10) I won’t give the entire book away, but suffice it to say it’s a fascinating read. I’m genuinely impressed at the advances science & medicine have been able to make into discoveries that are often stranger than fiction. Shoutout to @psmaldino for the book recommendation!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh