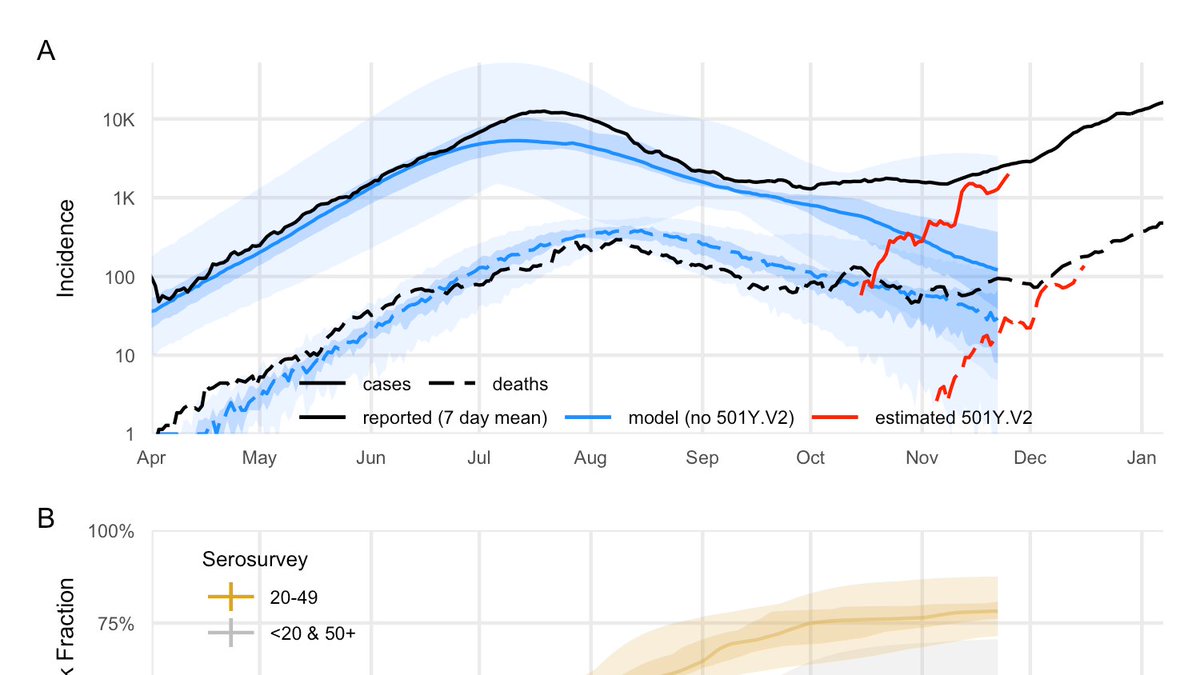

Analysis of novel SARS-CoV-2 variant in South Africa. Like the variant in the UK, 501Y.V2 is associated with a resurgence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

work w/ @timwrussell @_nickdavies @AdamJKucharski John Edmunds & @rozeggo

NB: NOT PEER REVIEWED cmmid.github.io/topics/covid19…

work w/ @timwrussell @_nickdavies @AdamJKucharski John Edmunds & @rozeggo

NB: NOT PEER REVIEWED cmmid.github.io/topics/covid19…

We calibrated a model used in a lot of @cmmid_lshtm COVID-19 work to the South African outbreak & interventions. In this model, to explain the increasing epidemic, 501Y.V2 needs to be either more transmissible or evading cross-protection.

NB: NOT PEER REVIEWED

NB: NOT PEER REVIEWED

If there is cross-protection against 501Y.V2, it's roughly 50% more transmissible. If it has the same transmissibility, then prior infection only confers 80% protection against 501Y.V2.

Both of these are big public health problems!

NB: NOT PEER REVIEWED

Both of these are big public health problems!

NB: NOT PEER REVIEWED

We also saw indications of increased severity, but many potential explanations there.

Both increased transmissibility and severity call for urgency in vaccination and continued vigilance in other measures, and continuing analysis of new variants.

#COVID19

NB: NOT PEER REVIEWED

Both increased transmissibility and severity call for urgency in vaccination and continued vigilance in other measures, and continuing analysis of new variants.

#COVID19

NB: NOT PEER REVIEWED

@threadreaderapp please unroll!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh