1/ In "stupid lawsuits over mean tweets" news, the 6th Cir. will hear arguments shortly in a case against @kathygriffin (save your personal opinions about her, I really don't care). Listen in here at 1:30 Eastern: ca6.uscourts.gov/live-arguments

2/ The case has flown mostly under the radar, likely because it was dismissed on the relatively unsexy issue of personal jurisdiction. But it's extremely important in cases about online speech (I'll add more to this thread later about that).

3/ The suit was brought by parents of Covington Catholic students that attended that infamous 'March for Life', who probably saw the Sandmann lawsuit and said "let's try to get rich off of this too!" There's no shortage of lawyers willing to help you on that quest.

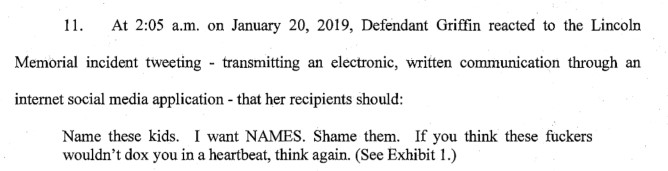

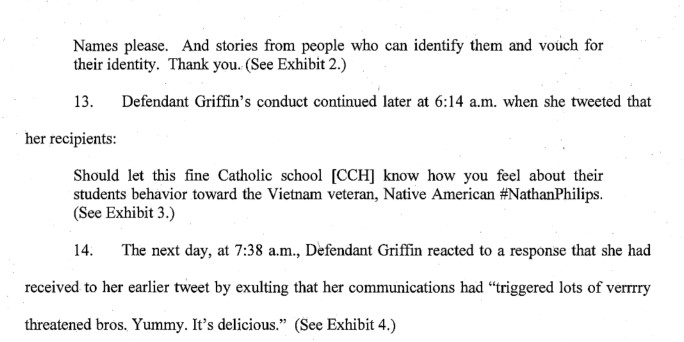

4/ The basis of the lawsuit is that during the whirlwind of coverage over the March for Life incident, Kathy Griffin sent some tweets about identifying the protesters seen in the videos that went viral.

Complaint: courtlistener.com/docket/1705913…

Complaint: courtlistener.com/docket/1705913…

5/ The lawsuit calls these tweets "doxing," which strikes me as kind of hyperbolic. I know some people disagree with me on this, but the identity of someone taking part in a public event (which is literally all Griffin asked for) is not particularly private information.

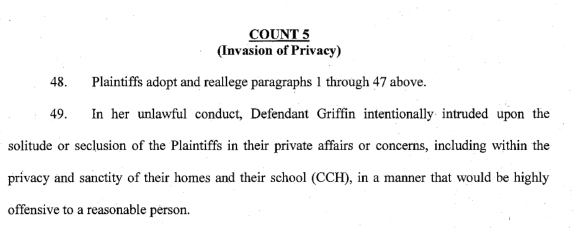

6/ The complaint brings five different causes of action, four of which are based on some really weird Kentucky thing that allows you to bring a civil case for an alleged violation of criminal law. Kentucky, man. Weird place.

7/ The first two are harassment claims. Harassment laws are already used in constitutionally suspect ways by prosecutors; they don't need any help from plaintiffs' lawyers.

8/ Remember: Griffin did not actually communicate with any of the people suing her. She wanted to know the identities of the protesters who were engaged in widely-discussed protests around matters of public concern.

9/ If asking about their identity a grand total of two times, or referring to registering displeasure with the school, is punishable as harassment, I've got some bad news for pretty much everyone on the Internet.

10/ Publicly involving one's self in matters of societal interest and concern comes with the corresponding right of others to discuss your involvement. Attempting to convert that into unprotected speech is an affront to the First Amendment and a risk to public discourse.

11/ The complaint then claims that Griffin engaged in "Threatening." This is pure spaghetti at the wall nonsense. Kathy Griffin didn't threaten to commit *any* crime, let alone one that is likely to result in death, serious injury, or property damage.

12/ Perhaps unsurprisingly, the plaintiffs' lawyer doesn't add much in the way of actually supporting this claim with, ya know, facts.

13/ Count 4 is more of the same, alleging that Griffin put the plaintiffs in reasonable apprehension of imminent physical injury. It's difficult to see how a tweet that admits to not even knowing who the plaintiffs are would put them in credible fear of injury, let alone imminent

14/ Count 5 is the only one that rests on actual tort law rather than some weird criminal-civil hybrid. But of course, it's hardly an intrusion into one's private life to identify them as having been part of a public protest covered by national media.

15/ The case is crap, and seeks to impose liability for speech that is undoubtedly protected by the First Amendment. But plaintiffs only see deep pockets, and it's very in vogue to sue people over mean tweets in certain communities.

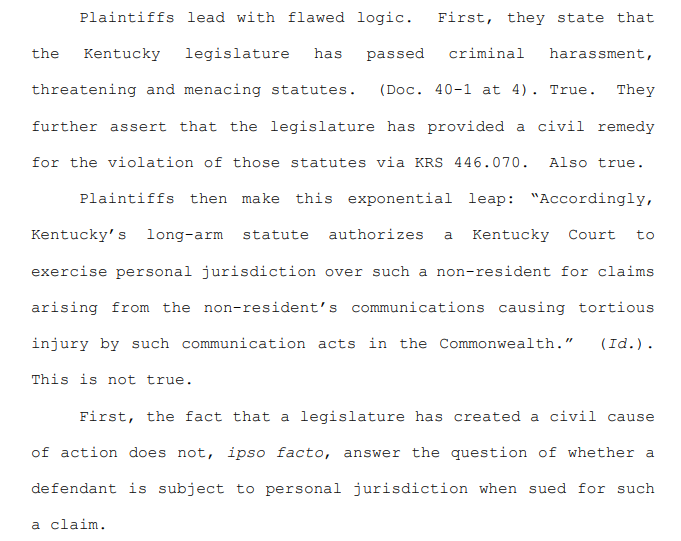

16/ Fortunately, the case never even got to the merits. Judge Bertelsman dismissed, holding that there was no personal jurisdiction over Griffin.

Decision: courtlistener.com/recap/gov.usco…

Decision on reconsideration: courtlistener.com/docket/1705913…

Decision: courtlistener.com/recap/gov.usco…

Decision on reconsideration: courtlistener.com/docket/1705913…

17/ Personal jurisdiction is a thorny and complex topic, but the very abridged version of this is that you can't just sue anyone anywhere. One of the ways that states provide for personal jurisdiction over out of state defendants is through "long arm statutes"

18/ Those laws permit states to exercise jurisdiction over defendants for engaging in a variety of acts that sufficiently connect them to the state such that it is not massively unfair to require them to defend themselves in that state's courts (to dramatically oversimplify)

19/ But when it comes to lawsuits about expression, it would be enormously dangerous to allow anyone to require someone who said something mean about them to defend themselves on the plaintiff's home court just because that's where the target of the speech lives.

20/ And the courts have repeatedly held that simply feeling the injury in a place (even if the defendant knew where the plaintiff lived) is not sufficient to create jurisdiction.

21/ Instead, the defendant has to create a sufficient connection to the place where the lawsuit is brought to support personal jurisdiction. (Again, this is an oversimplification because I can't give you a personal jurisdiction lecture on Twitter)

22/ Were it otherwise, you could force anyone on the Internet to defend themselves across the country on completely bogus claims. The result would be madness, and it would be untenable.

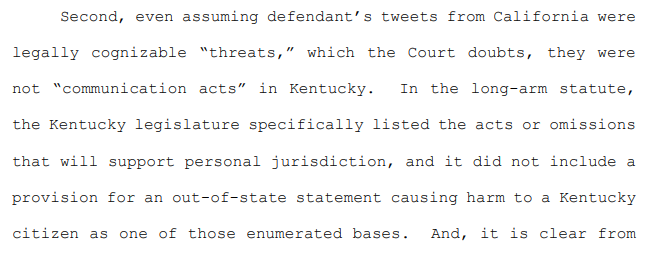

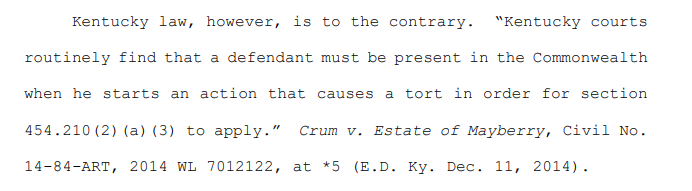

23/ And as Judge Bertelsman noted, the KY long-arm statute only gives the courts jurisdiction over tortious acts committed in the state (Griffin quite obviously is not a KY resident; she tweeted from CA).

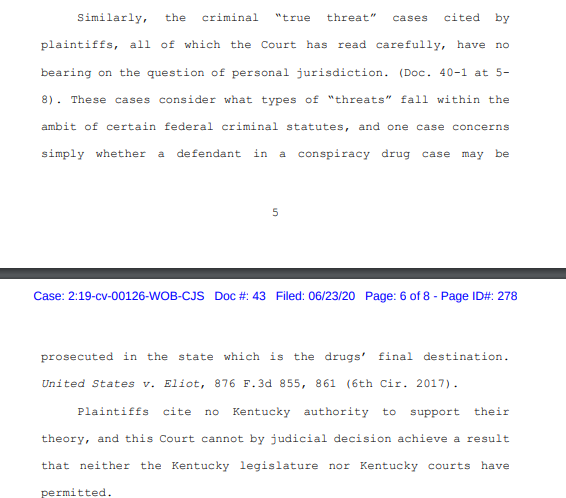

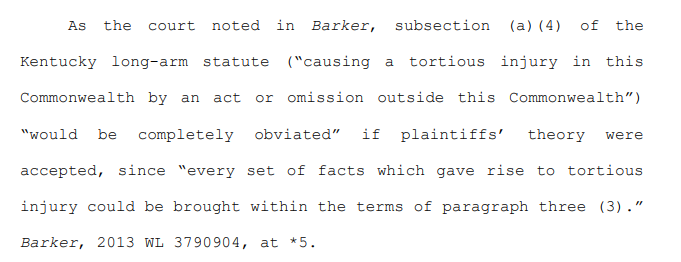

24/ Plaintiffs try to get around this by saying that because they were suing under criminal statutes, and because KY itself could prosecute Griffin if it wanted to, then surely the intent was to give civil litigants the same reach as the state.

26/ It is clear to me from the briefs (next tweet) that plaintiffs' counsel is woefully outmatched. But even if the 6th Circuit reverses on personal jurisdiction, there is no way in hell this should survive a motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim.

It's a bad lawsuit.

It's a bad lawsuit.

27/ Appellants' Brief: pdfhost.io/edit?doc=e6415…

Appellee's Brief: pdfhost.io/edit?doc=7f93e…

Reply Brief: pdfhost.io/edit?doc=1130b…

Appellee's Brief: pdfhost.io/edit?doc=7f93e…

Reply Brief: pdfhost.io/edit?doc=1130b…

28/ Please stop suing people about mean social media posts. It's really dumb.

29/ Also COME ON KENTUCKY, WHAT THE FUCK ARE YOU DOING WITH YOUR STATUTES.

30/ Here is the audio if you want to listen to oral arguments:

31/ Plaintiffs' counsel wasting time on the stupid argument that filing an appearance some time before filing a motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction (but nothing in between) is SO STUPID.

32/ Judge has a concern that plaintiff focusing on criminal law standards doesn't really line up with the KY long-arm statute in civil cases.

Like, duh.

Like, duh.

33/ This lawyer just doesn't seem to get that just because the legislature made criminal behavior tortious doesn't mean they meant to grant civil litigants equal reach to state prosecutors.

Judge to plaintiffs' counsel:

"That's a very odd way to read the staute."

Readers, I chuckled.

"That's a very odd way to read the staute."

Readers, I chuckled.

35/ This answer to the judge's question "what's your best case" is not particularly clear, concise, or good.

He is arguing that KY was trying to extend jurisdiction to all acts that harm KY residents.

That would be unlikely to survive scrutiny even if it were true.

He is arguing that KY was trying to extend jurisdiction to all acts that harm KY residents.

That would be unlikely to survive scrutiny even if it were true.

36/ Now he is arguing that tweets are just another form of communication so that any tweet constitutes an act within the Commonwealth of Kentucky.

That is an absolutely untenable and ridiculous argument.

That is an absolutely untenable and ridiculous argument.

37/ Now he's talking about true threats, and I fear he will shortly say something really stupid because there is no true threat here.

38/

"These ARE true threats," he confidently proclaims, proceeding to destroy his own argument by listing things that she did with absolutely no connection to any legitimate threat of bodily harm.

"These ARE true threats," he confidently proclaims, proceeding to destroy his own argument by listing things that she did with absolutely no connection to any legitimate threat of bodily harm.

39/

Counsel's argument boils down to "doxing [N.B. not doxing] people by calling for their identity to be known is automatically a true threat"

Counsel's argument boils down to "doxing [N.B. not doxing] people by calling for their identity to be known is automatically a true threat"

39/

Judge asks if he runs into a First Amendment argument.

Counsel AUDIBLY SIGHS, and then ignores the question by saying "well true threats aren't protected."

This guy is way out of his depth.

Judge asks if he runs into a First Amendment argument.

Counsel AUDIBLY SIGHS, and then ignores the question by saying "well true threats aren't protected."

This guy is way out of his depth.

40/

First counsel on the other side is for a defendant in a related case (which was consolidated).

He correctly points out that nobody is being prosecuted, implying that the whole "actus reus" discussion was bullshit (and it was)

First counsel on the other side is for a defendant in a related case (which was consolidated).

He correctly points out that nobody is being prosecuted, implying that the whole "actus reus" discussion was bullshit (and it was)

41/ Counsel: The court has held that a letter sent from out of state, WHICH PLAINTIFF JUST SAID IS NO DIFFERENT FROM A TWEET, is not an act within the state of KY under the long-arm statute.

L O fucking L

L O fucking L

42/

Counsel: It would be bonkers to allow plaintiffs to get around the long-arm statute just by alleging that a defendant violated a criminal statute. That position enjoys no support in law. The law is clear and specific.

This is a good argument.

Counsel: It would be bonkers to allow plaintiffs to get around the long-arm statute just by alleging that a defendant violated a criminal statute. That position enjoys no support in law. The law is clear and specific.

This is a good argument.

43/ With respect to due process, the civil/criminal distinction is even less relevant; this is a federal constitutional issue.

Under Walden, it is the *defendant* who must create contacts to the forum state by availing herself of something within the state.

This is correct.

Under Walden, it is the *defendant* who must create contacts to the forum state by availing herself of something within the state.

This is correct.

44/ Citing 10th Cir, "Internet communications are peculiarly non-territorial communications."

That's why this case is important. There has to be some cabining on jurisdiction for things floating out in the Internet aether.

That's why this case is important. There has to be some cabining on jurisdiction for things floating out in the Internet aether.

45/

The judges have not interrupted this defendant's lawyer once. Probably because he's saying things that are right, and non-controversial.

Not good for plaintiff.

The judges have not interrupted this defendant's lawyer once. Probably because he's saying things that are right, and non-controversial.

Not good for plaintiff.

46/ Now up, Kathy's lawyer

47/ He's going to address the claim that Griffin waived her objection to personal jurisdiction because her lawyer filed notice of appearance before objecting.

48/ Two part test:

1) Did the defendant's submission give the impression that she was submitting to jurisdiction or

2) Did the defendant do something that would have been a waste if personal jurisdiction was found to be lacking

1) Did the defendant's submission give the impression that she was submitting to jurisdiction or

2) Did the defendant do something that would have been a waste if personal jurisdiction was found to be lacking

49/ N.B.: This is just such a silly thing to be arguing. If I were a judge and the only thing filed was a notice of appearance and a litigant raised a stink saying that was a waiver, I would put the fear of god into them.

50/ "The reading of Gerber being urged by plaintiffs is fundamentally incompatible with FRCP 12."

In order to waive this fundamental due process right, it must be knowing and voluntary. Only two ways to do it: Fail to make a motion (which Griffin did),

In order to waive this fundamental due process right, it must be knowing and voluntary. Only two ways to do it: Fail to make a motion (which Griffin did),

51/ or failure to raise it as a defense in a subsequent responsive pleading.

There is simply no way that a notice of appearance is a responsive pleading. This argument makes no sense.

He is 10000% correct, and the judges should needle plaintiffs' counsel about this.

There is simply no way that a notice of appearance is a responsive pleading. This argument makes no sense.

He is 10000% correct, and the judges should needle plaintiffs' counsel about this.

52/

It used to be that you had to file a special appearance to object to personal jurisdiction in order to not waive, but that rule has been abandoned in most (all?) courts.

It used to be that you had to file a special appearance to object to personal jurisdiction in order to not waive, but that rule has been abandoned in most (all?) courts.

53/

The district court judge said he doesn't buy that there's a distinction between waiver and forfeiture. Counsel disagrees, saying that forfeiture should be where you raise an objection but then give it up through conduct in litigaiton.

Either way, Griffin should win.

The district court judge said he doesn't buy that there's a distinction between waiver and forfeiture. Counsel disagrees, saying that forfeiture should be where you raise an objection but then give it up through conduct in litigaiton.

Either way, Griffin should win.

54/ Time's up for Griffin's lawyer, plaintiff reserved 3 minutes for rebuttal.

55/ Plaintiff believes that the Gerber case is a bright-line, strict rule.

He argues you don't have to file any kind of appearance, so if you do it's a waiver.

That would be weird.

He argues you don't have to file any kind of appearance, so if you do it's a waiver.

That would be weird.

56/ "Defendant's arguments are the arguments advanced by the concurrence, so it can't be that the case held that"

57/ Judge wants to go back to long-arm. Why aren't we bound by the case law about the out of state letter, since we are sitting in diversity. That case said that a letter sent from out of state was not an act within the state. Do you dispute that holding's applicability?

Boom.

Boom.

58/ Counsel: It's not applicable because the letter never went to the plaintiff, it was not direct communication.

Judge: Uh, same thing with the tweet here.

lol.

Judge: Uh, same thing with the tweet here.

lol.

59/ Counsel: "we're not talking about invasion of privacy" (THEN WHY DID YOU INCLUDE THE CAUSE OF ACTION) and we are talking about true threats...

Judge: cuts him off, basically saying "yea yea I get it."

Judge: cuts him off, basically saying "yea yea I get it."

60/

Argument over. That went very well for the defendants, and very stupidly for the plaintiffs.

Argument over. That went very well for the defendants, and very stupidly for the plaintiffs.

P.S./

I generally don't live tweet arguments/hearings but holy hell I now have an even greater appreciation for people who do.

It's not easy, folks, especially when you're dealing with technical concepts.

I generally don't live tweet arguments/hearings but holy hell I now have an even greater appreciation for people who do.

It's not easy, folks, especially when you're dealing with technical concepts.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh