Charles Lenox Remond was the most prominent Black abolitionist in the US until he was overshadowed by Frederick Douglass.

Remond’s commitment to women’s rights was as deep as FD’s, maybe deeper. He should be remembered for his feminism.

Long thread.

Remond’s commitment to women’s rights was as deep as FD’s, maybe deeper. He should be remembered for his feminism.

Long thread.

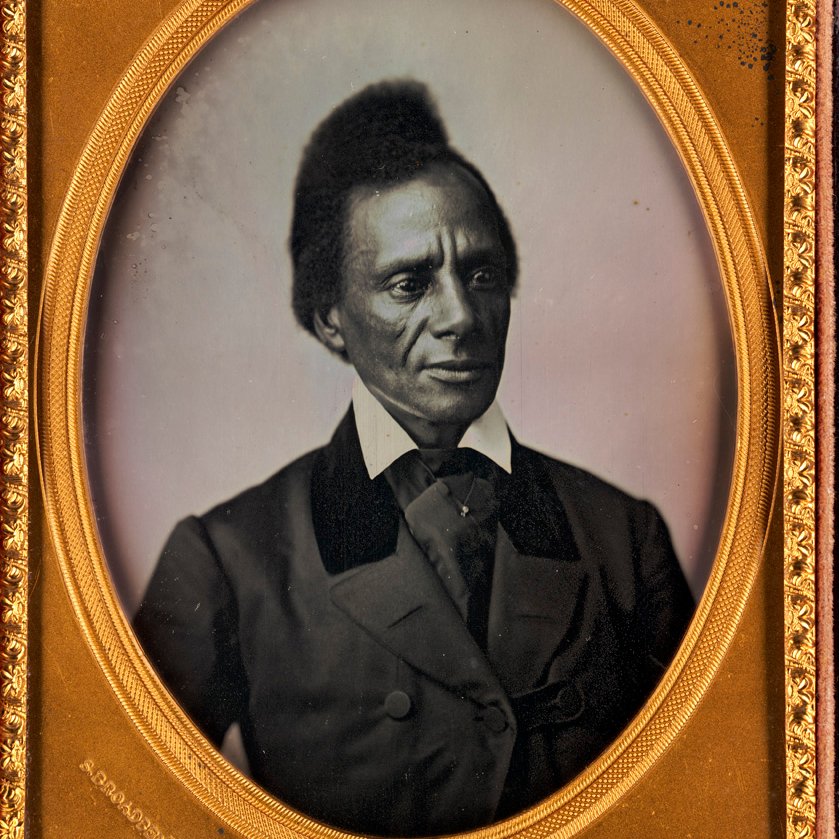

Charles Remond was the oldest son of eight children of Nancy Lenox and John Remond of Salem, Massachusetts. He had six sisters. Their grandfather fought in the Revolutionary War.

The photograph above was taken in the 1850s by Samuel S. Broadbent. via @BPLBoston

The photograph above was taken in the 1850s by Samuel S. Broadbent. via @BPLBoston

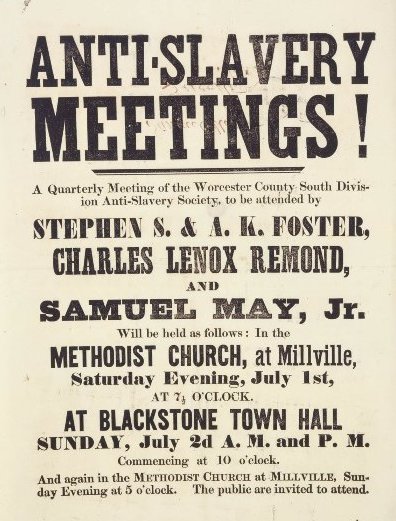

Until Charles Remond, the most visible spokespeople for abolition were white. Remond was a founder of the American Anti-Slavery Soc. & the first Black man to lecture widely against slavery.

In 1840, he was invited to join a delegation to the World Antislavery Conventn in London.

In 1840, he was invited to join a delegation to the World Antislavery Conventn in London.

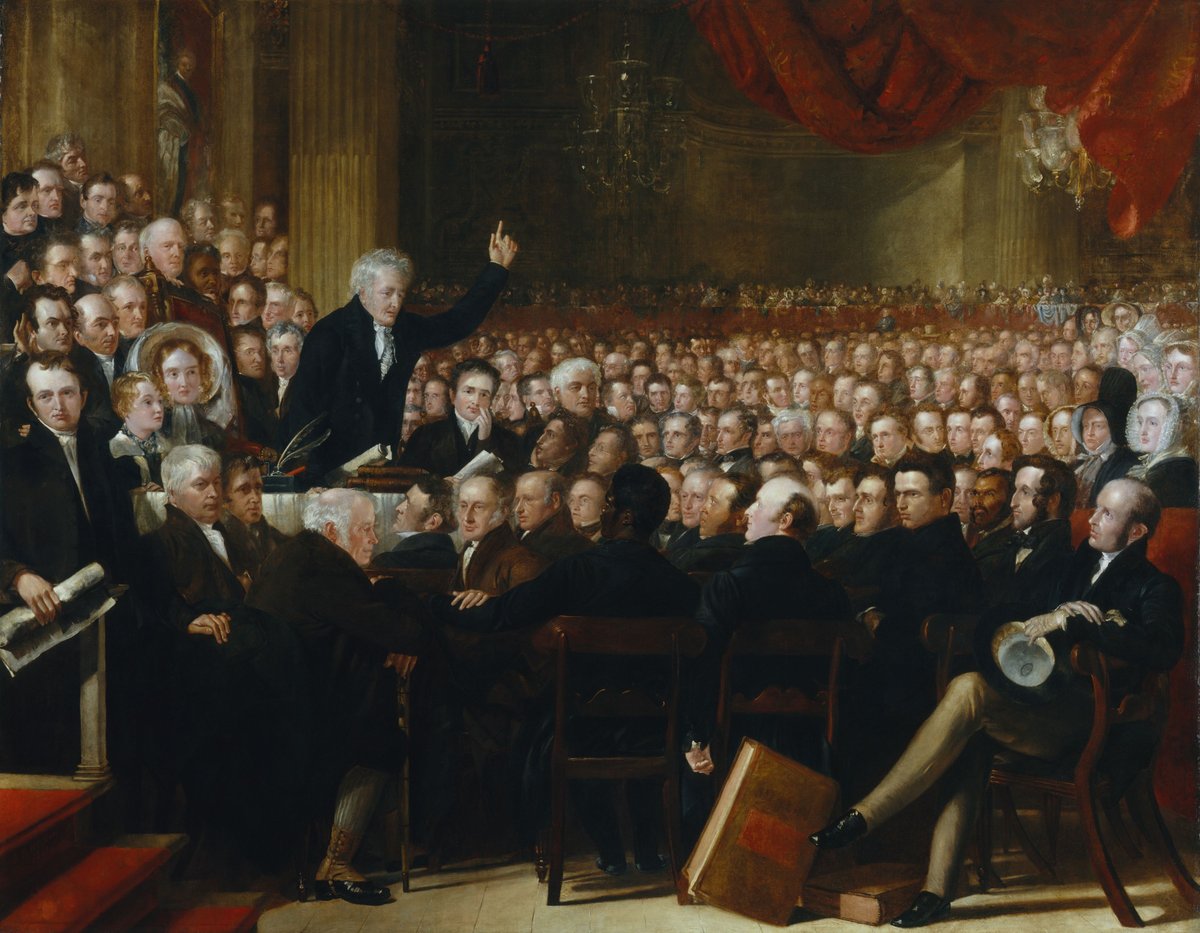

In the US & UK, abolitionists had been arguing for months over whether women could participate equally. Misogyny had caused a schism in the US movement. Multiple US delegations went to London. One, from Philadelphia, sent four women; other groups were all men.

Charles Remond was part of another delegation that included William Lloyd Garrison and Lucretia Mott.

About Mott, perhaps the greatest woman of her era, Garrison asked: “In what assembly is that almost peerless woman NOT qualified to take an equal part?”

About Mott, perhaps the greatest woman of her era, Garrison asked: “In what assembly is that almost peerless woman NOT qualified to take an equal part?”

This one, apparently. The London organizers refused to seat the female delegates.

Charles Remond was *the only Black delegate to the entire convention.*

Everyone was watching to see what he would do.

Charles Remond was *the only Black delegate to the entire convention.*

Everyone was watching to see what he would do.

Remond refused to take his seat if women could not. He and Garrison sat in the gallery with the women. You can find him in the painting.⏫

Remond said later that it was a matter of respect--he would not disrespect the women whose dogged fundraising underwrote the trip.

Remond said later that it was a matter of respect--he would not disrespect the women whose dogged fundraising underwrote the trip.

Back home, the men were hailed for “refusing to lower a noble principle to accommodate a barbarous custom.” A special resolution added: “We, the colored citizens of Boston, feel ourselves ably represented at antislavery meetings in England in the person of Charles Lenox Remond.”

Throughout his life, he leveraged his privilege as a man. In 1848 he opened an African American Anti-Slavery Society meeting in Philadelphia by specifying that “any gentleman _or lady_ who may desire to address the meeting” could do so. @marthasjones_

Remember, this was 1848!

Remember, this was 1848!

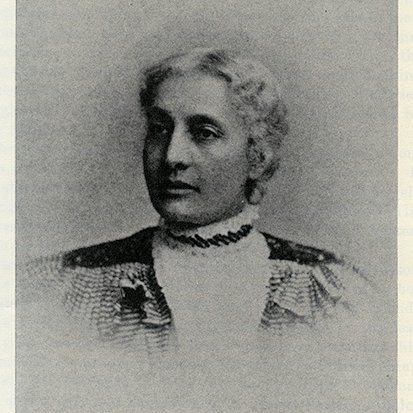

Women’s public participation was still novel. Harriet Purvis ⬇️ was on the business committee at that meeting, with other Black women. Lucretia Mott was there too, and she was impressed at the breadth and inclusivity of the agenda: “the cause of the slave, as well as of women."

At the Colored National Convention in 1855, Charles Remond proposed Mary Ann Shadd for membership. She was one of two women there, having journeyed back from Windsor, Ontario, where she edited The Provincial Freeman, a newspaper for the Black emigrant community.

Remond moved to admit Mary Ann as a “corresponding member” representing the Canadian emigrant population - which was fraught for two reasons. Whether to leave or stay and fight in the US was a heated dispute, and she was the only émigré at the meeting.

She was also one of only two women there, and not all men thought women should participate. “This question gave rise to a spirited discussion,” per Jane Rhodes’ biography & @CCP_org. Her membership was approved 38-23, after Remond and Frederick Douglass fought for her.

In 1859, Charles declined to be nominated to the business committee of the New England Convention of Colored Citizens, saying "it was time to elect women to leadership positions in the organization.” (Terborg-Penn)

A man *stepped back* explicitly to make room for women.

A man *stepped back* explicitly to make room for women.

By this time, Charles Remond frequently shared a podium with his sister Sarah. She was 16 years younger than he, and becoming an accomplished activist and orator in her own right.

In 1866-67, Sarah and Charles toured New York campaigning for universal suffrage. A state constitutional convention was planned for 1867, and it was an opportunity to correct two major wrongs. No woman could vote in NY, and Black men had to meet an impossibly high property tax.

The state refused to make progress on either front. New York restricted voting by Black men until 1874; by Black women until 1917.

Soon after their speaking tour, Sarah Remond moved to Italy, where she became a doctor and lived the rest of her life.

Soon after their speaking tour, Sarah Remond moved to Italy, where she became a doctor and lived the rest of her life.

Charles Remond died in Boston in 1873. He stood up for his sisters, all of them. Early in his life when he had plenty to lose, and later when he was more established, he used his power to benefit women.

#Suffrage100 #BlackSuffragists #SuffrageMen

#Suffrage100 #BlackSuffragists #SuffrageMen

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh