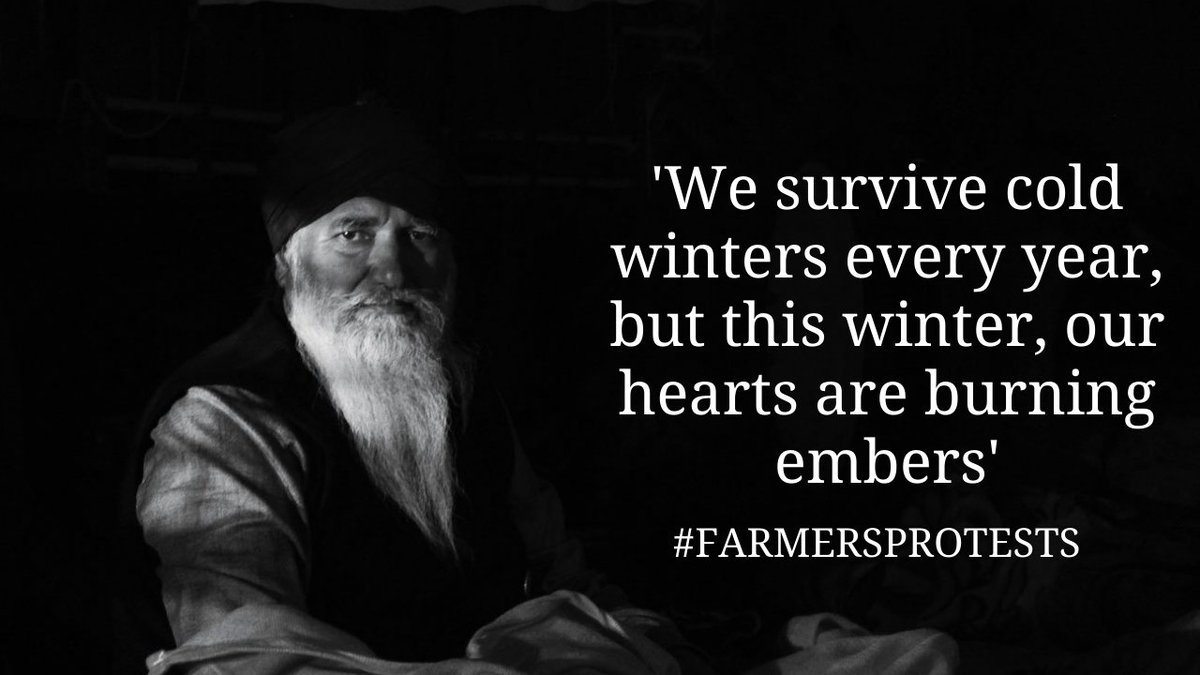

Women are central to agriculture in India, and many of them – young and old, across class and caste lines – are present and resolute at the #FarmersProtests sites around Delhi. A photo thread this #MahilaKisanDiwas

ruralindiaonline.org/en/articles/wo…

ruralindiaonline.org/en/articles/wo…

Bimla Devi (in red shawls), 62, with her sister Savitri (60) reached the #SinghuBorder on Dec. 20 to tell the media that her brothers and sons protesting there are not terrorists. "I started crying seeing how the media was talking about my sons.” 2/n

Vishavjot Grewal’s family owns 30 acres of land in Pamal village of Ludhiana district, where they mainly cultivate wheat, paddy, and potatoes. “We want the reversal of these [farm] laws,” says the 23-year-old, who came with relatives to Singhu in a mini-van on December 22. 3/n

Mani Gill, 28, from Punjab’s Faridkot district has an MBA and works in the corporate sector. She's a volunteer with a youth-run platform that helps create awareness about farmers’ issues on social media. “We try to bring forth issues that farmers face every day,” she says. 4/n

“I came because farmers need support from youth. People are here regardless of their caste, class, and culture” says 24-year-old Komalpreet from Kot Kapura village in Faridkot. She came to the Singhu border on December 24 and volunteers with a youth-run platform. 5/n

Sajahmeet (right) and Gurleen have been participating at different farmers’ protest sites since Dec 15. “It was very difficult to remain at home knowing that they needed more people at the protests. We go wherever the help is required,” says the 28-year-old from Patiala. 6/n

“The govt. is pretending that these laws are good for farmers, but they are not. It is exploiting us, if not, they would have given us an assurance of MSP in writing. We cannot trust our govt.” says Harsh Kaur (extreme right) who holds a BA in Journalism. 7/n

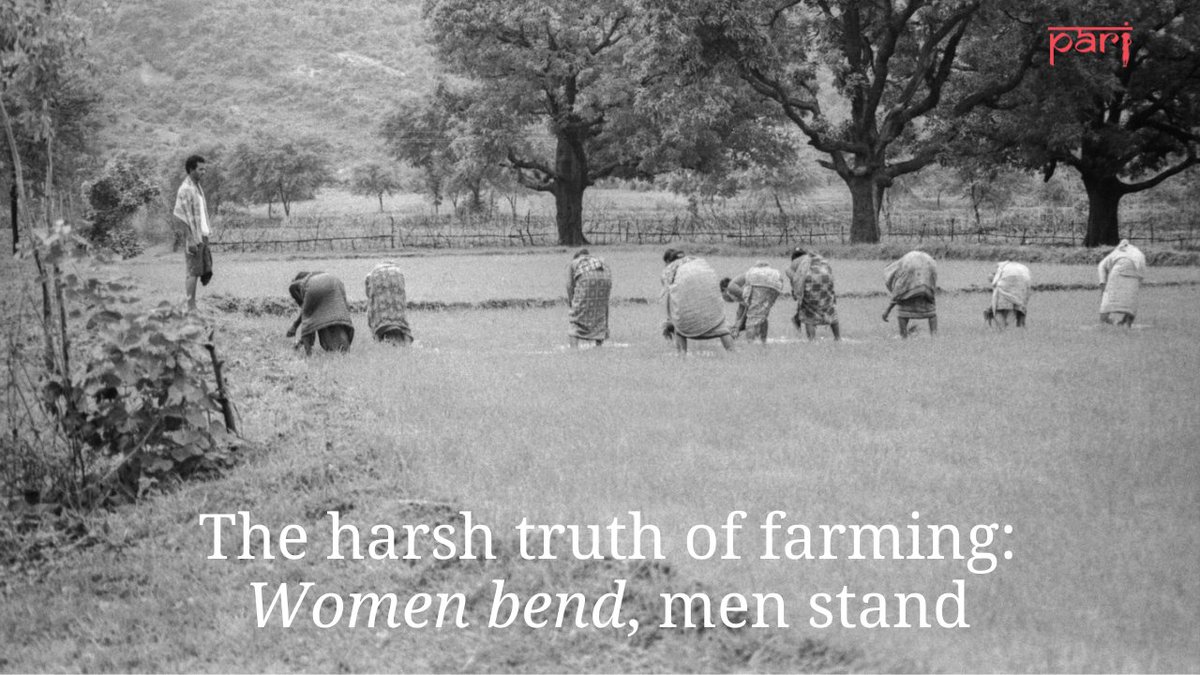

“Women are going to be the worst sufferers of the new farm laws. Though very much involved in agriculture, they do not have decision-making powers. The changes in the Essential Commodities Act will create a lack of food and women will face the brunt of it,” says Mariam Dhawale

Resham and Beant Kaur, who are among the protestors at Delhi's borders, emphasise that the farm laws will impact the livelihoods and food security of innumerable households of farm labourers, like their own family. 9/n

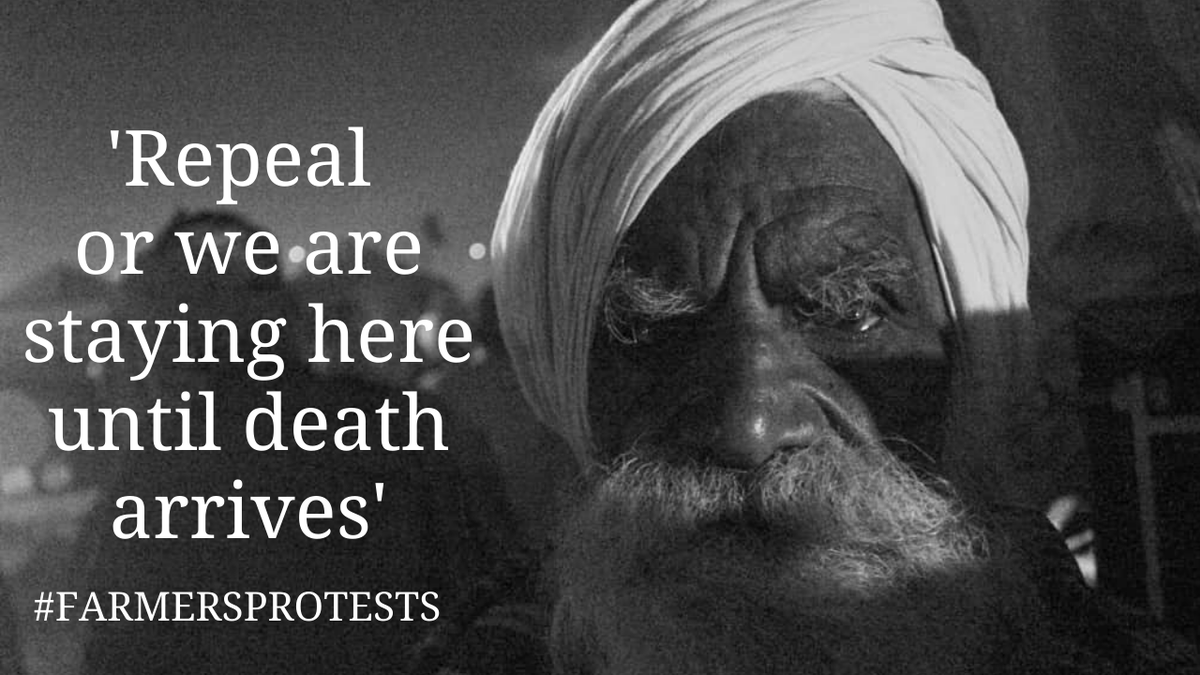

On Jan 11, the Chief Justice of India passed an order putting the 3 farm laws on hold, said that women and the elderly must be ‘persuaded’ to go back from the protest sites. But the fallout of these laws concerns and impacts women (the elderly) too. And they are protesting [fin]

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh