Today in pulp: why didn't the ancient Greeks write science fiction?

That's a good question. No, really. Come this way...

That's a good question. No, really. Come this way...

Drama, poetry, rhetoric: the ancient Greeks not only created wonderous art they also thought deeply about how to perfect it. Aristotle's poetics is still a key touchstone for this after two and a half millennia.

The ancient Greeks also excelled at science, mathematics and philosophy, building on Egyptian and Babylonian knowledge. Theoretical and practical enquiry abounded.

So why didn't they combine the two? Why don't we see speculative science-based narrative works in ancient Greece? Why didn't Urania and Calliope get together, so to speak?

Well there were some attempts. The Nature of the Universe by Lucretius tried to explain Epicurian philosophy to a mostly Roman audience: atomism, causality, indeterminism are all brought to life through his verses as he explores Greek cosmology.

But Hellenistic cosmology is mostly associated with planetary movements: it is often mathematical in nature, and the mechanics of the celestial progression take precedence to speculative enquiry about what planets and stars are actually composed of.

Life on Earth, the things in front of us, are more often than not the subjects of Greek science: from Leucippus's atomism to Plato's ideals of form to the five classical elements. The stars are less fascinating than the world we live in.

Cosmogony - the origin of the universe - is left to the Gods. They are the prime movers of creation, and as they live on Earth it's there rather than in the heavens that any lyrical action takes place.

We sometimes forget how seriously the Greeks considered the actions of the Gods in regards to creation. Cause and necessity had to flow from some source, and the will of divine, immortal and often capricious beings was not illogical.

That said, there are some fascinating Hellenistic models of the cosmos. The Pythagorean philosopher Philolaus postulated that the Earth, Moon, Sun and planets all revolve around an unseen Central Fire.

Now we can't see this Central Fire that Zeus placed at the centre of the cosmos because the Earth, like the Moon, is tidally locked and doesn't rotate. Europe looks away from the fire and thus sees the Sun rise and fall. We orbit the unseen Fire every 24 hours.

But there's more. How does Earth stay permanently in orbit around the Fire? Because there is a counterweight - a second Earth - at the opposite point of our orbit! Now that's got science fiction written all over it!

Alas the counter Earth is just a rocky mass like the Moon, bereft of life because it is bereft of Gods. Earth is where the action is and speculative fiction set elsewhere wasn't really a captivating idea for the Greeks.

But maybe we're approaching this from the wrong angle. What exactly is science fiction? Where did it come from and why? Well I'm with Brian Aldiss on this - though other views are available!

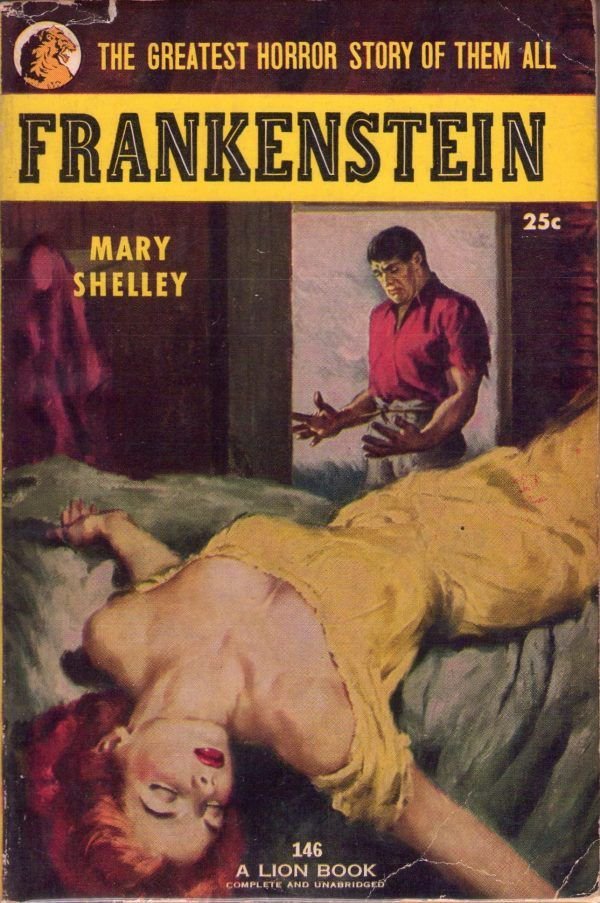

Aldiss saw SF as beginning with one key novel: Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley. The story of a scientist who creates artificial life and is doomed by the moral consequences of his actions. It is the progenitor of science fiction as a genre.

Now many people argue otherwise - de gustibus non disputandum est as they say. But one key idea flows from Aldiss's viewpoint: SF is a heart a branch of the Gothic. And that's very interesting...

The Gothic is many things, but one of these things is that it sits in counterpoint to the Enlightenment. It holds in its heart those types of knowledge - emotional, revelatory and sublime - that the Enlightenment holds in lesser regard.

And it's in that space between the rational/material and the emotional/sublime that SF works its magic. What do we gain, and what do we lose, by privileging Enlightenment knowledge? Can we explore this through speculative science?

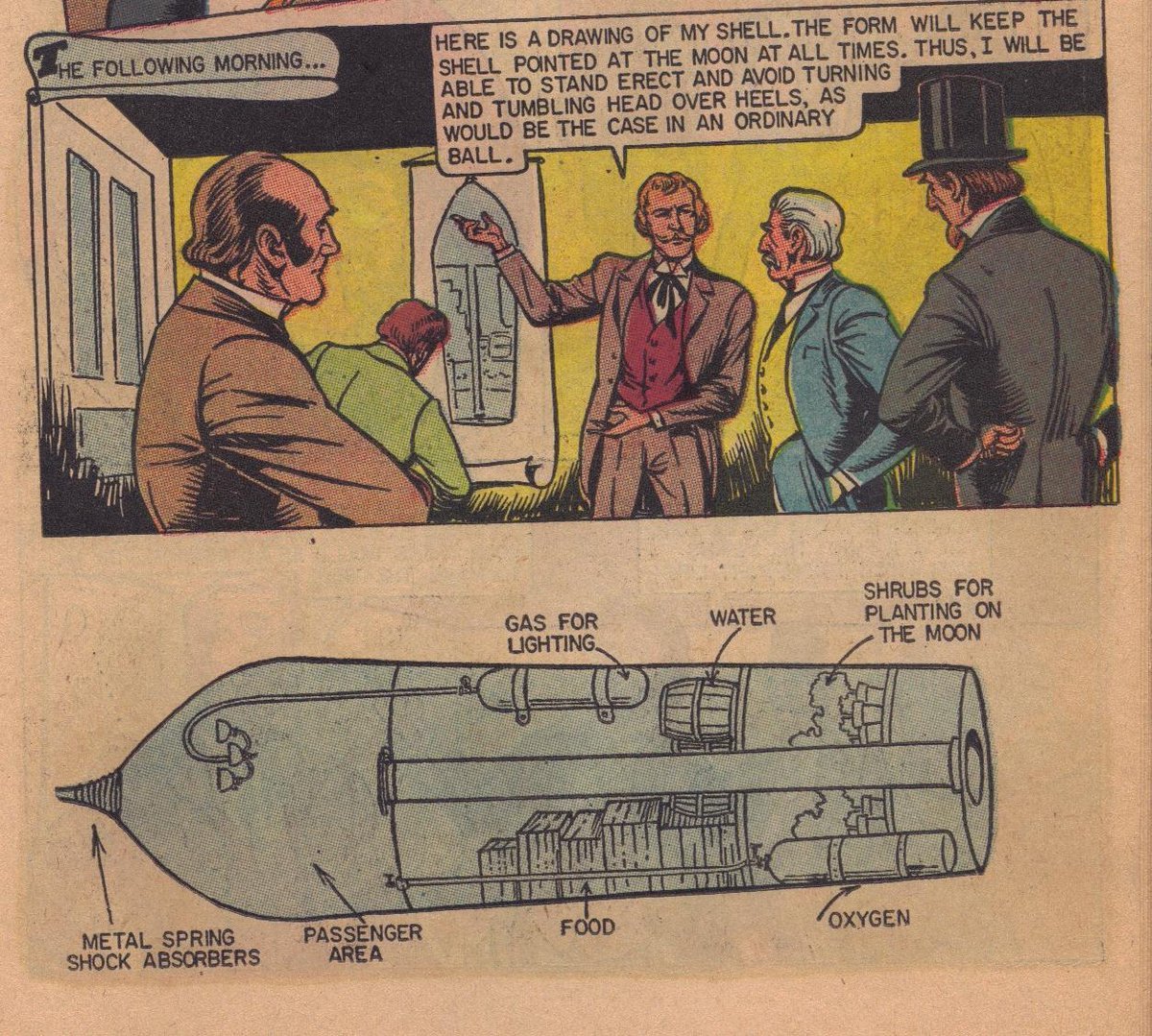

Now we're used to SF being an adventure story with speculative underpinnings - you can thank Jules Verne for that, or more accurately his publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel who thought this was more saleable.

But SF keeps circling back to the Gothic. Every new generation of SF writers seems to come back to the dramatic possibilities in the tension between the Gothic and the Enlightenment. At least for a while.

And for me that's why ancient Greece didn't do SF. There was no tension between these things in a scientific world created by capricious Gods. Zeus didn't make you choose between emotion and rationality. You could have it all!

More random speculations another time...

More random speculations another time...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh