In a blinded name-swap experiment, black female high school students were significantly less likely to be recommended for AP Calculus compared to other students with identical academic credentials. Important new paper from @DaniaFrancis:

smith.edu/sites/default/…

smith.edu/sites/default/…

Some background: one of the best ways to collect real-world evidence of discrimination is through name-swapping "audit" studies. In these experiments, people are presented with job applications, resumes, mortgage applications, etc., that are identical except for the name…

The applicant’s name is varied to suggest the individual’s race/ethnicity/gender. Think “John” vs “Juan” or “Michael” vs. “Michelle”.

These audit studies have demonstrated significant discrimination in a variety of contexts. For instance, “John” is more likely to be hired than “Jennifer” for a scientific position, even if they have otherwise-identical resumes. pnas.org/content/109/41…

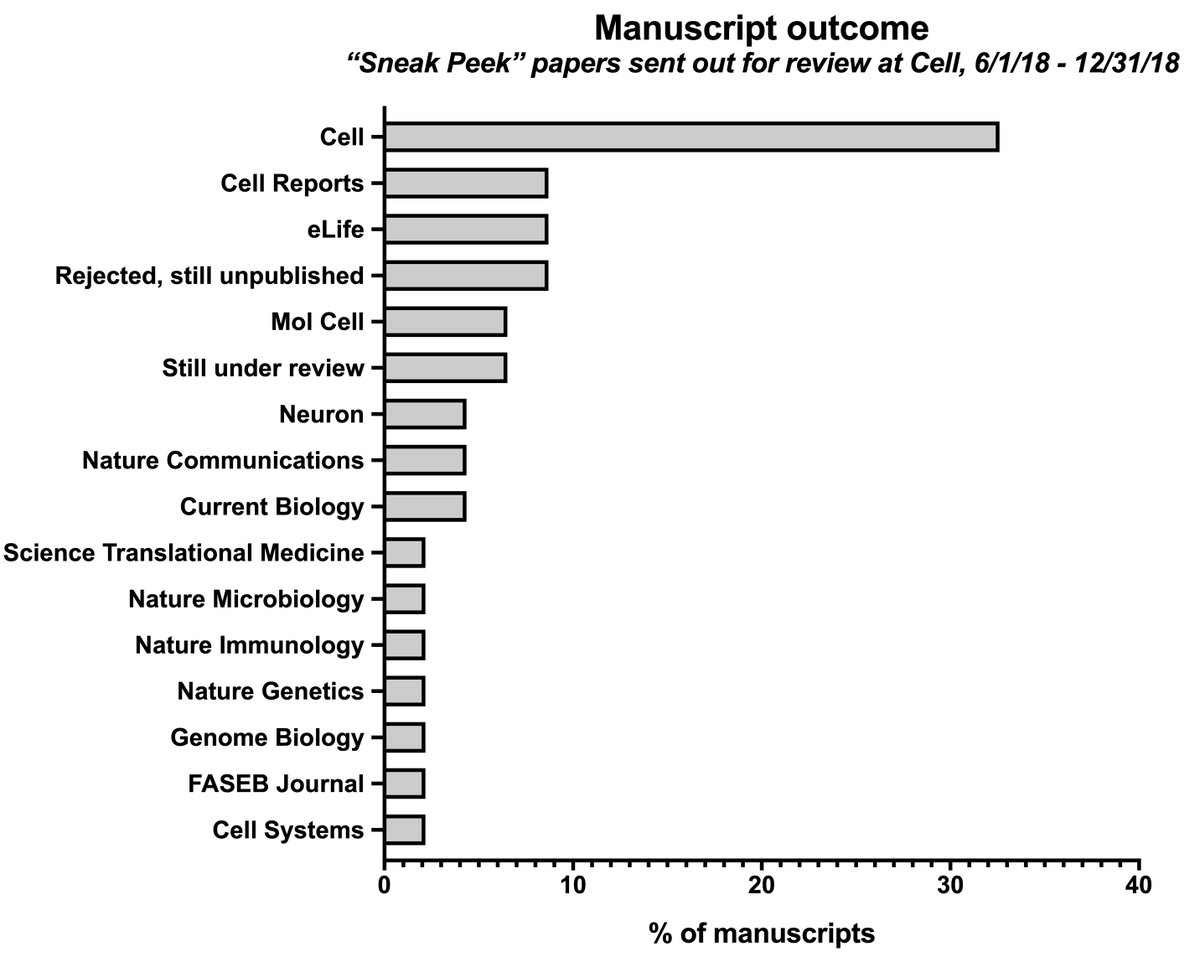

This new paper used an audit methodology to investigate something different - who gets tracked into an Advanced Placement math class. AP classes are heavily weighed for college admissions, so this choice can have significant ramifications for a student's future.

The researchers in this current study set up a booth at a national education conference and invited school counselors to review different student transcripts. The transcripts either had no name, or had a name to suggest the student’s race/gender.

The counselors were then asked how likely they were to recommend that the student take AP calculus.

The researchers found that when a transcript showing strong grades was given a black female name, counselors were 20% less likely to recommend them for AP calc compared to an identical but anonymous transcript.

You can see that other gender/race combinations mostly cluster around 1. But in three of four experiments, the black female student was less likely to be recommended for AP calc compared to the nameless transcript. “Black female” was significant in the pooled analysis as well:

These frustrating results underscore the prevalence of implicit biases even among school guidance counselors.

I think about these results in terms of the “cumulative advantage” theory of inequality: one decision (like taking AP Calc) may not be huge by itself, but a lifetime of being 20% less likely to recommended for honors, promotions, etc. can add up to a lot: annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.114…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh