"Tired of reality? Escape into the world of role-playing games." In particular one whose corporate history is a wild mix of battle, quests and the fickleness of fortune.

Today in pulp... the story of Dungeons & Dragons!

Today in pulp... the story of Dungeons & Dragons!

The history of Dungeons & Dragons and its parent company TSR is complex, like the game. It's full of feuds, schisms, colourful characters, chance happenings and fabulous riches. Again, like the game. So where to begin?

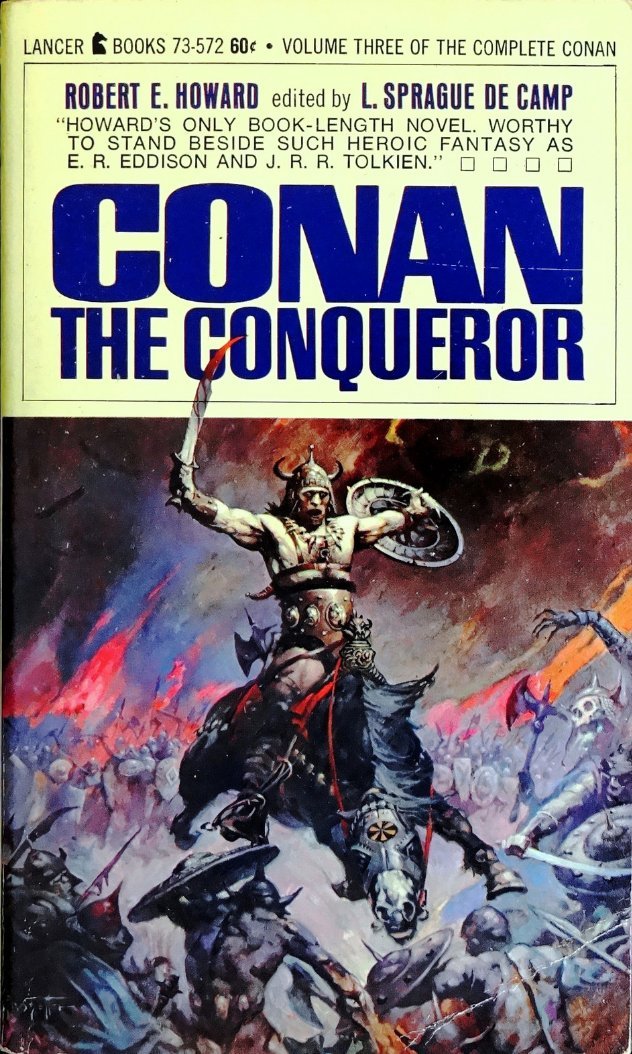

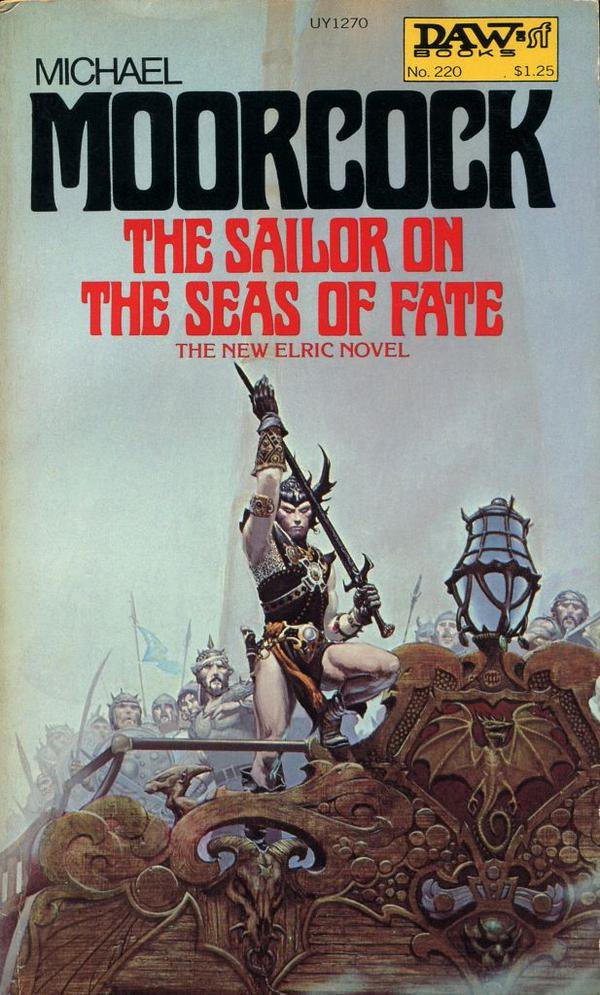

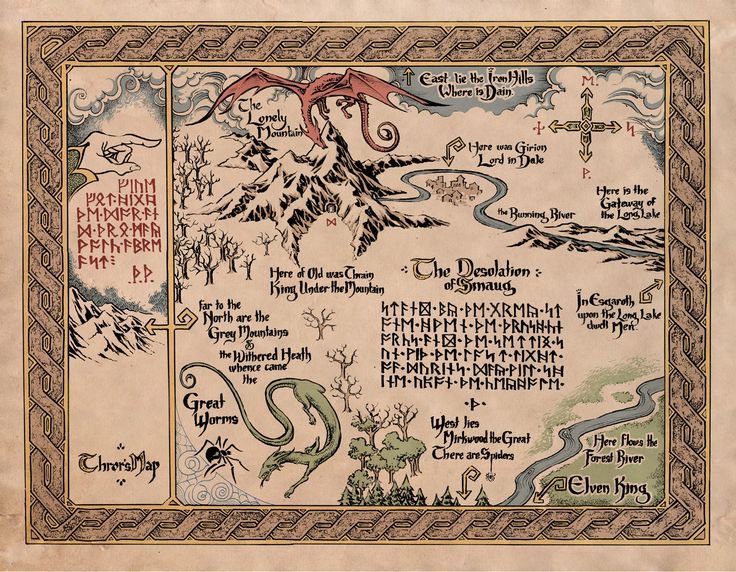

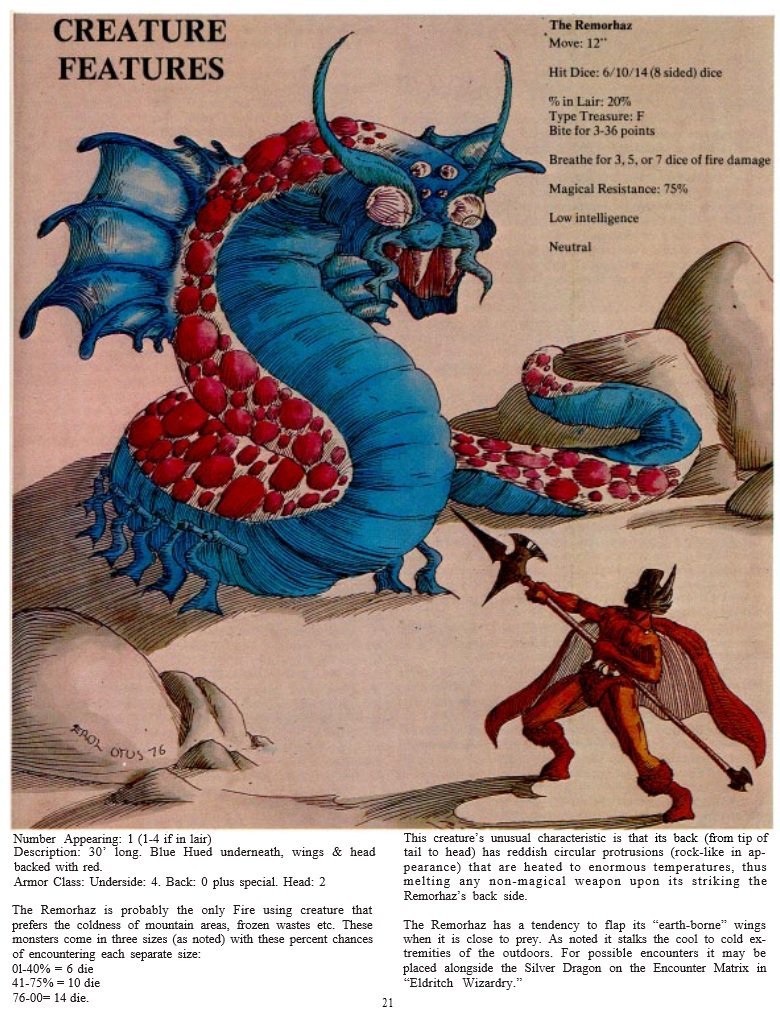

Pulp fiction - especially Robert E Howard, Michael Moorcock and Fritz Lieber - was a huge influence on Dungeons & Dragons: monsters, spells, magic armour and complex class systems all feature in it, derived from the ultimate ur-text - Lord of the Rings.

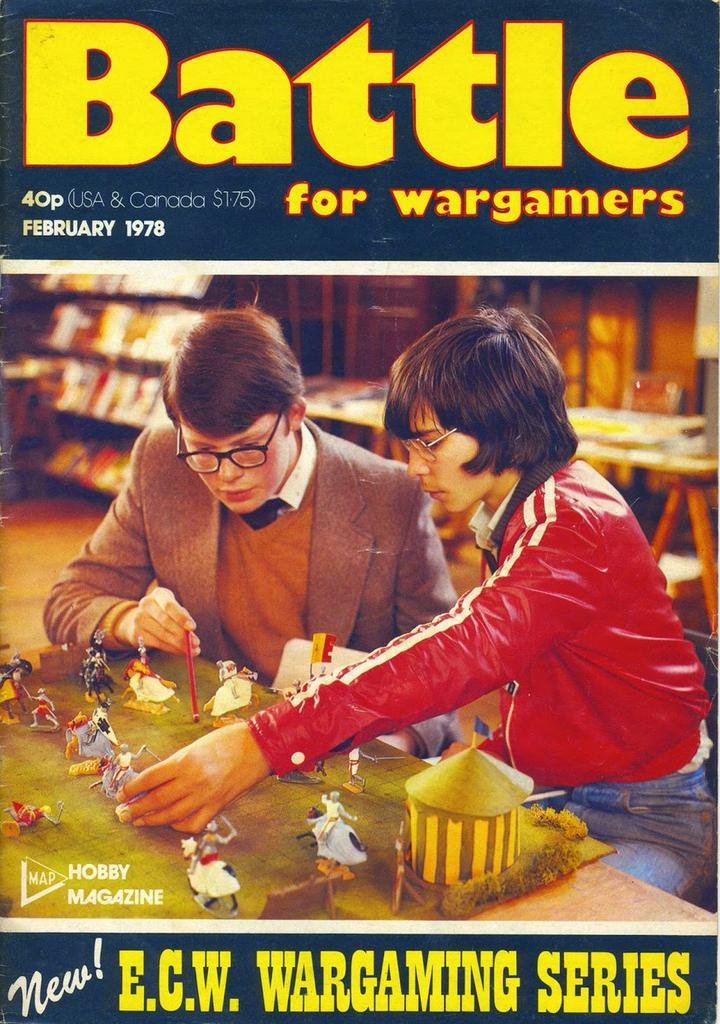

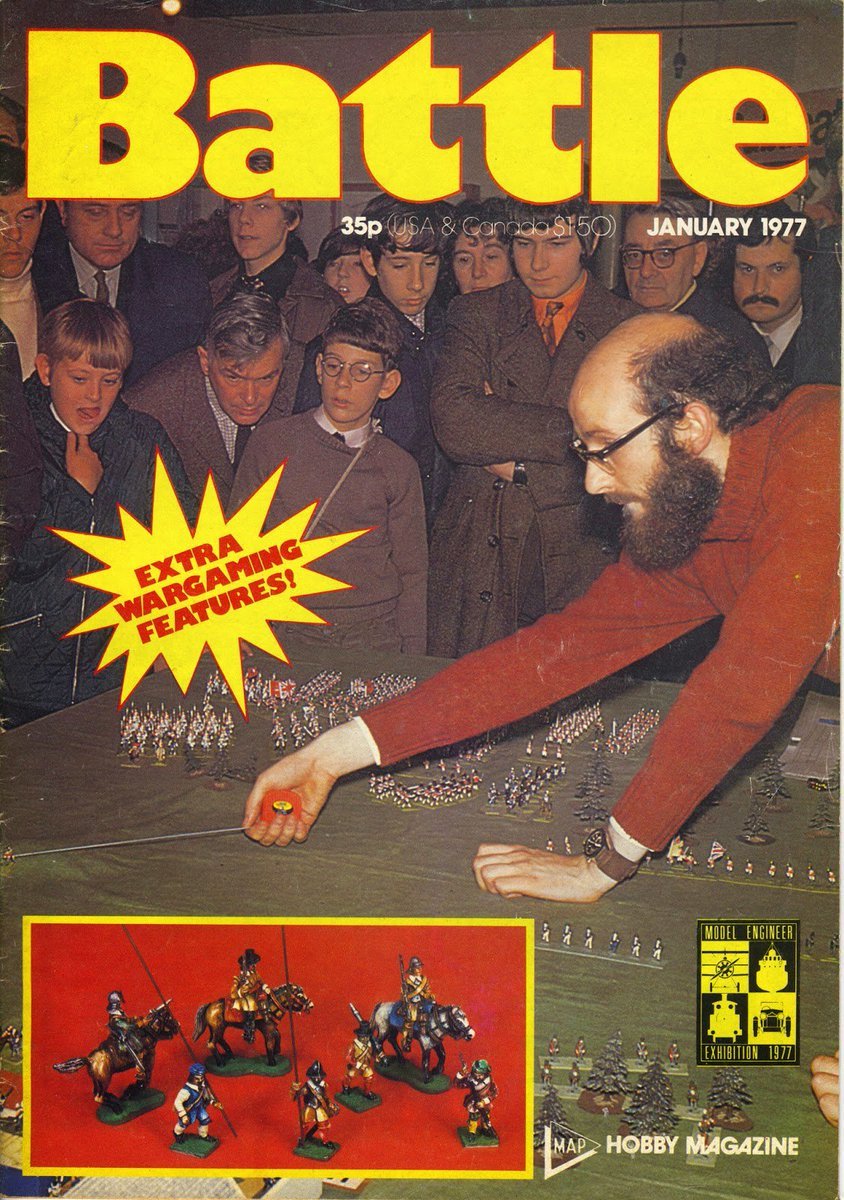

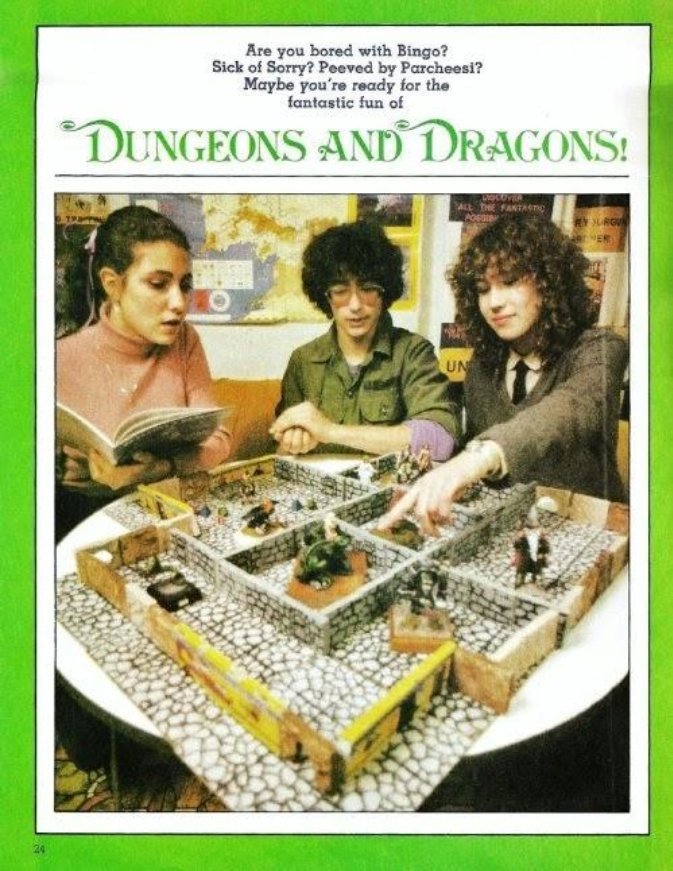

Dungeons & Dragons was also a rebellion against traditional wargaming, with its historical armies lined up in miniature on model scenery. Tape measures were a key part of historical wargaming. Fantasy and storytelling weren't.

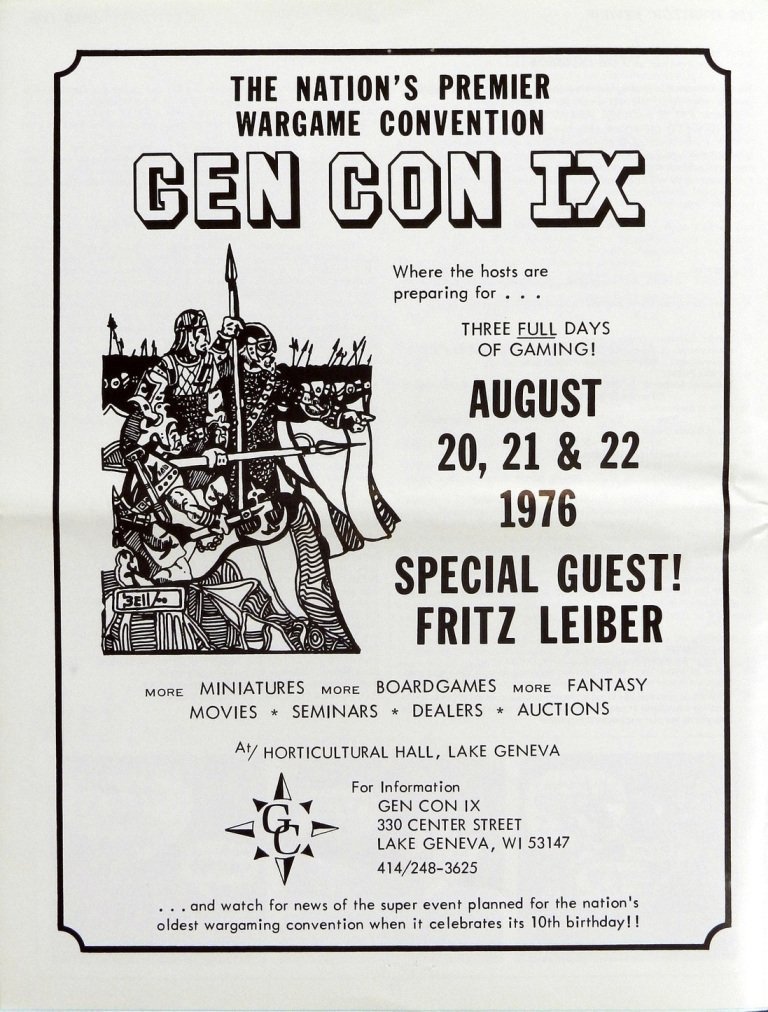

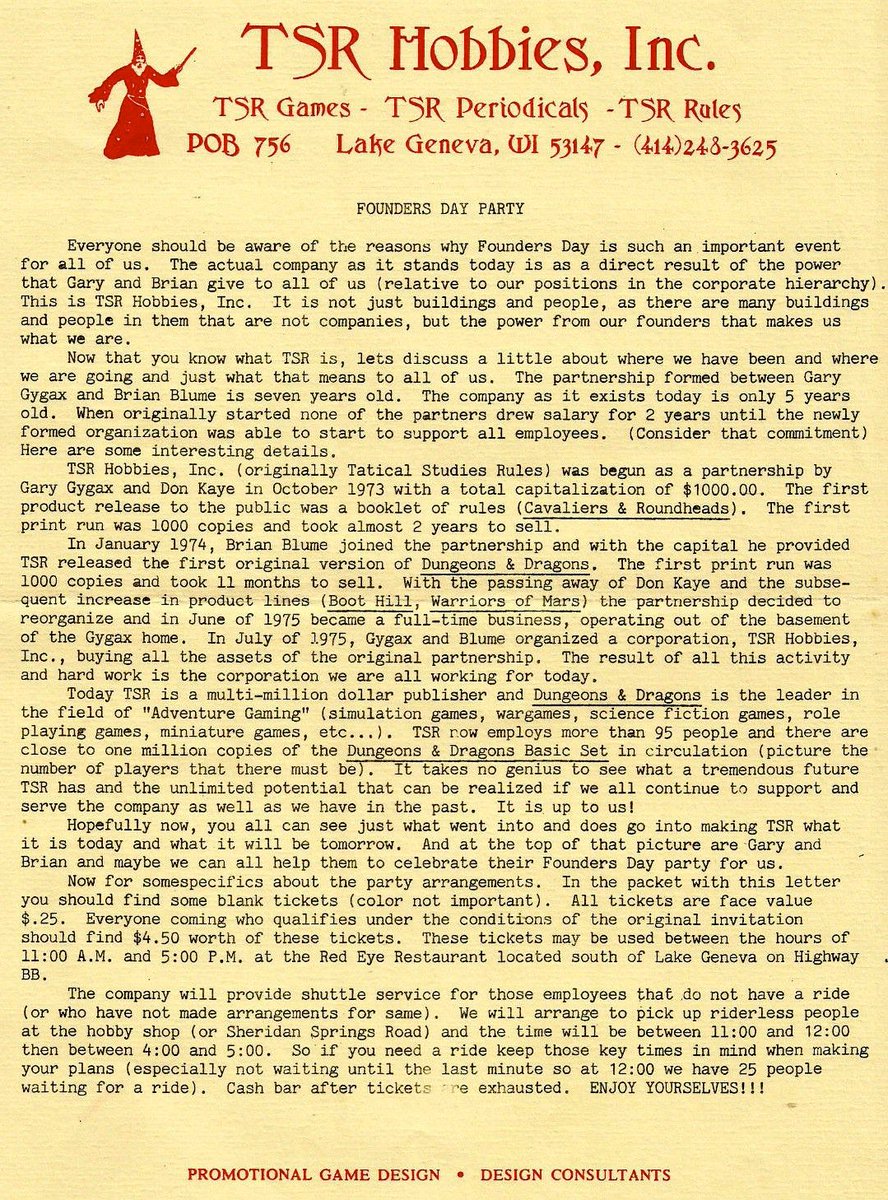

The story of Dungeons & Dragons starts with Gary Gygax, who co-founded the International Federation of Wargamers in 1967. A year later he launched Gen Con, an event to bring gaming fans together. By 1970 the Lake Geneva Tactical Studies Association was founded - in his basement.

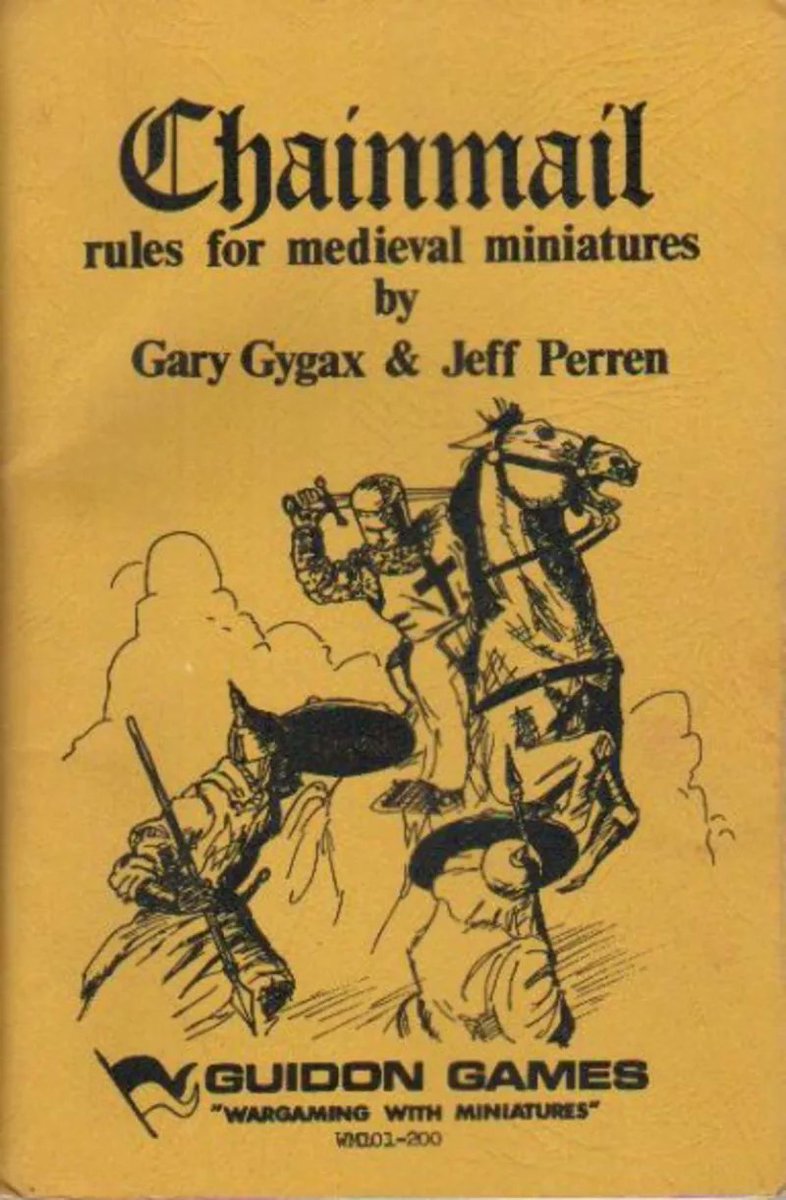

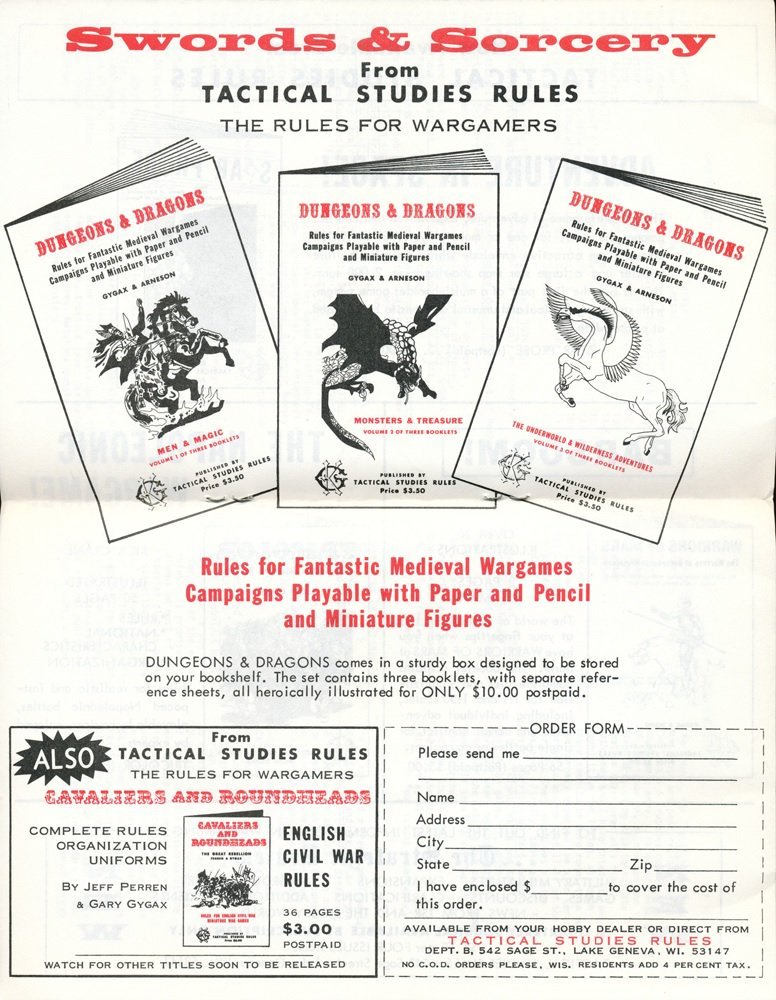

Chainmail was created in 1971 by Gary Gygax and Jeff Perrin as a medieval wargame. But it came with a supplementary set of rules for fantasy wargaming: dragons, trolls, spells and magic swords could now be part of the gameplay.

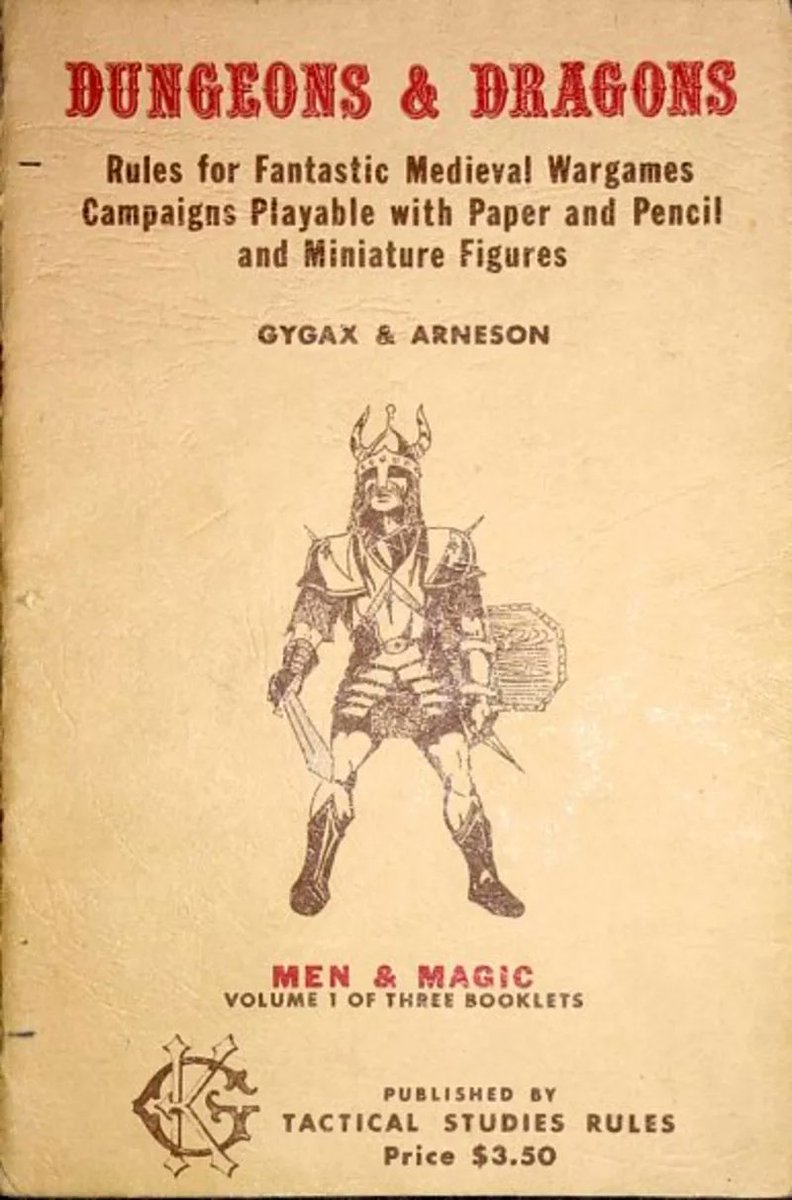

In 1973 Gygax and Dave Arneson - who had met at Gen Con in 1969 - built on the Chainmail rules to create the first Dungeons & Dragons fantasy game. Gary Gygax also founded TSR (Tactical Studies Rules) to market it.

Unlike traditional miniature wargames, in Dungeons & Dragons you managed a specific character rather than an army. Players worked together (or not) to solve problems, fight battles and gain experience. A Dungeon Master acted as storyteller and referee.

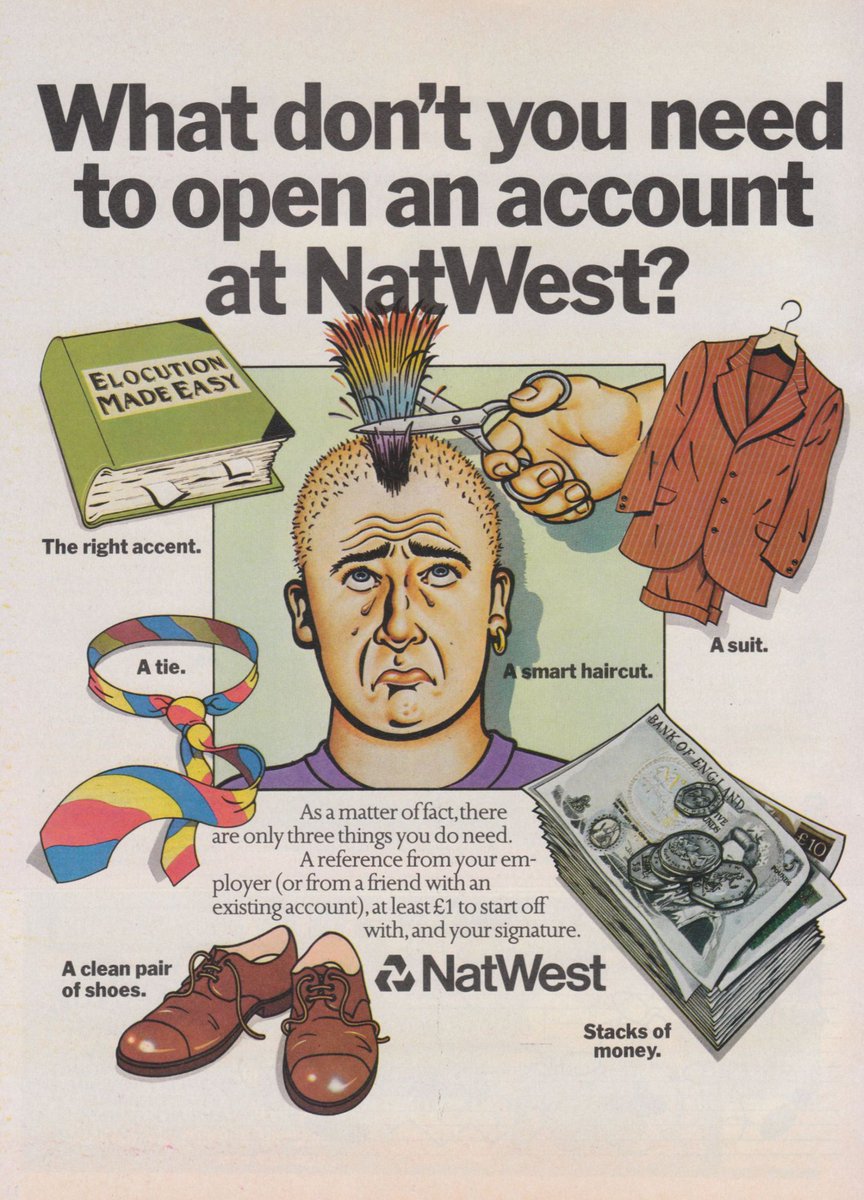

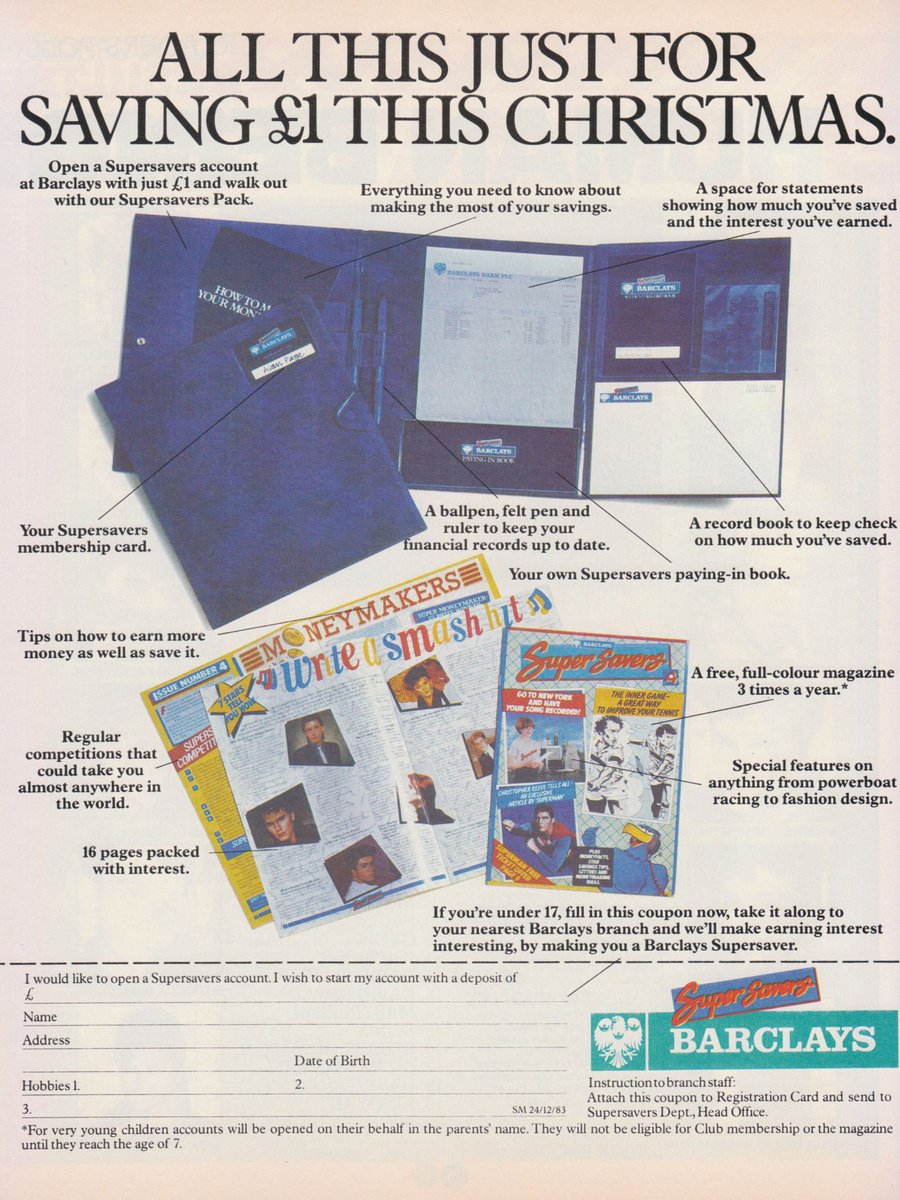

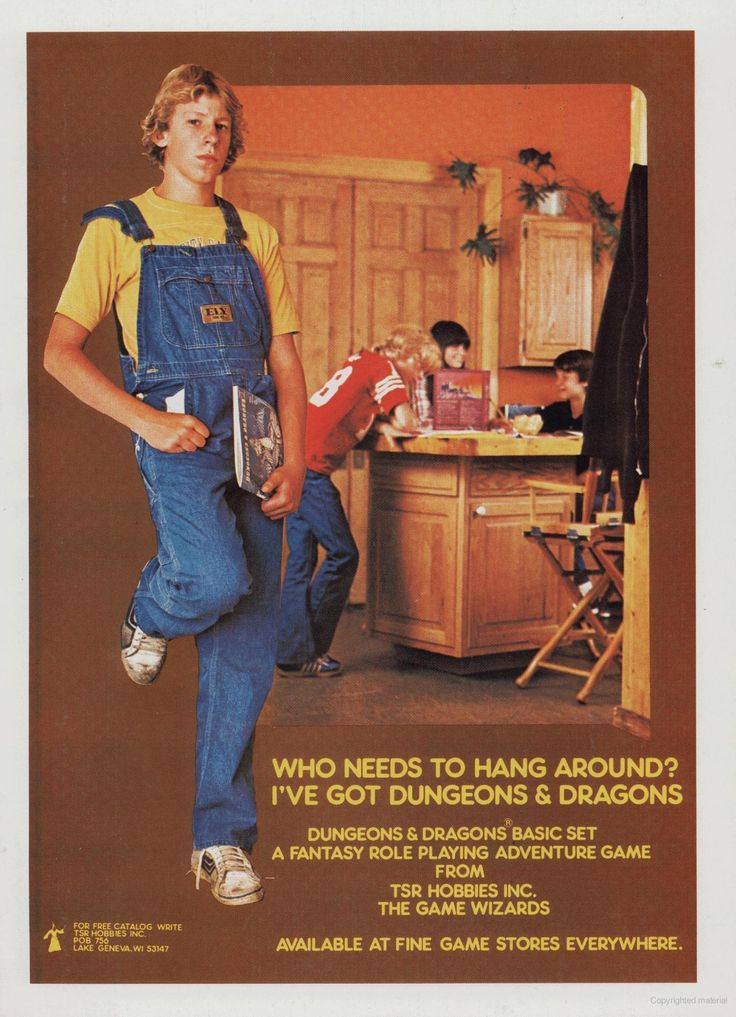

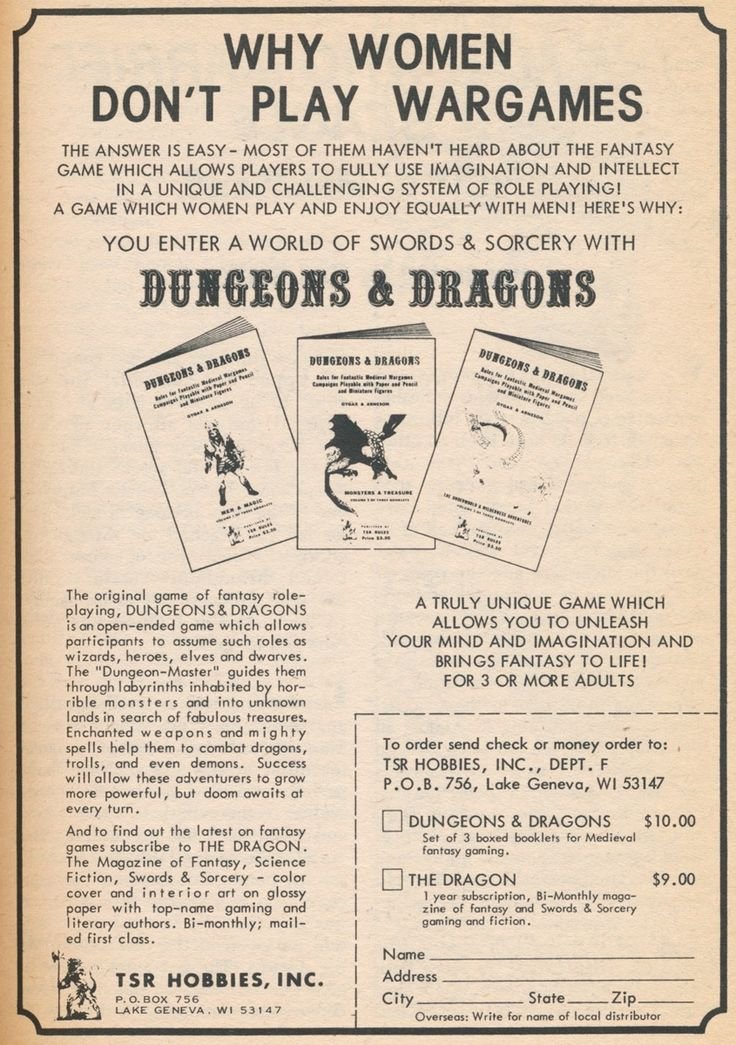

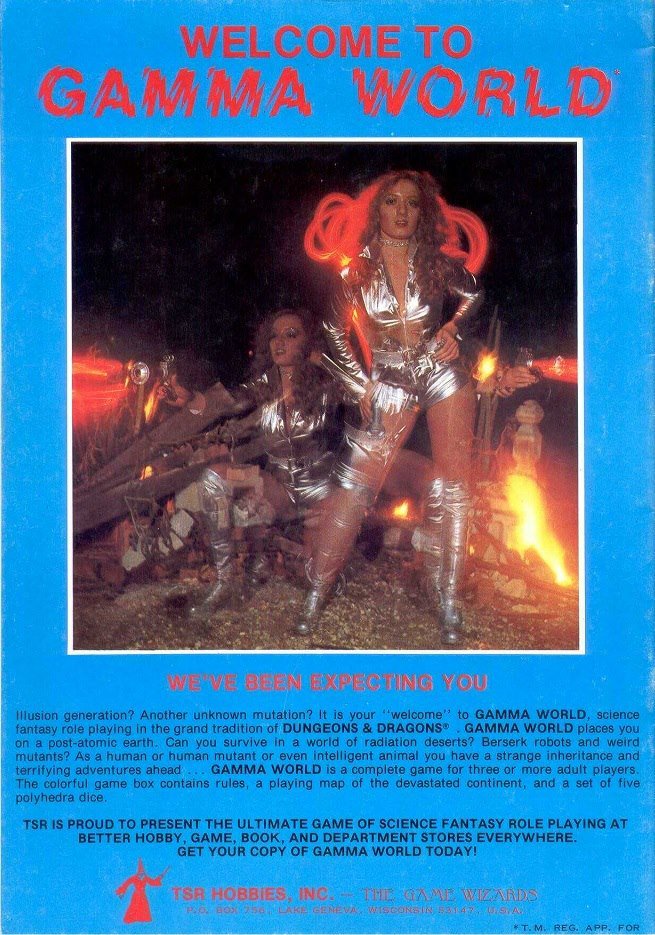

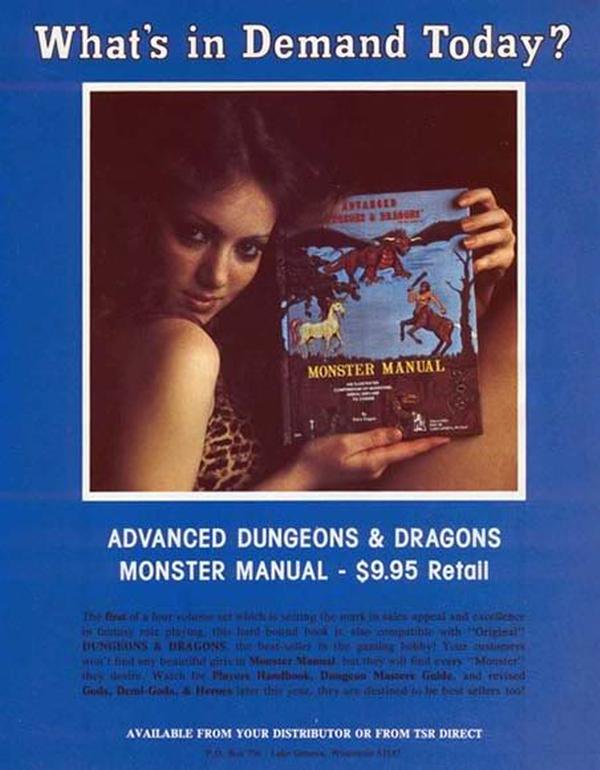

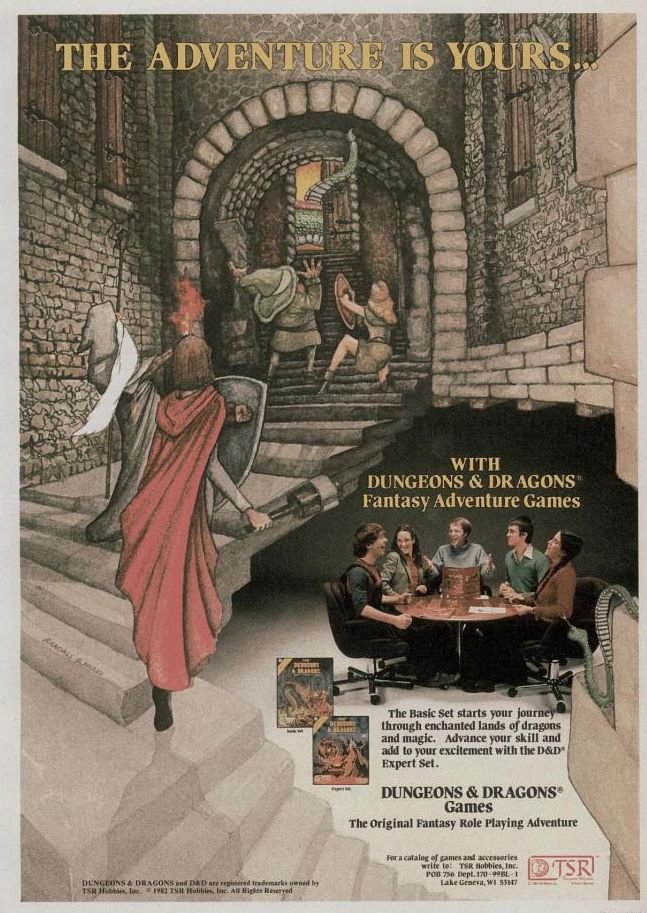

From the beginning TSR tried hard to shake off the 'boys in basements' image of role-playing games. Mary Elise Gygax fronted some of the early TSR marketing, though by today's standards it does look a bit corny.

TSR itself was an unorthodox company. Finally incorporated in 1975 its governance structure was designed to ensure no non-wargamer could control the company. Initially shares were only granted to friends or family members.

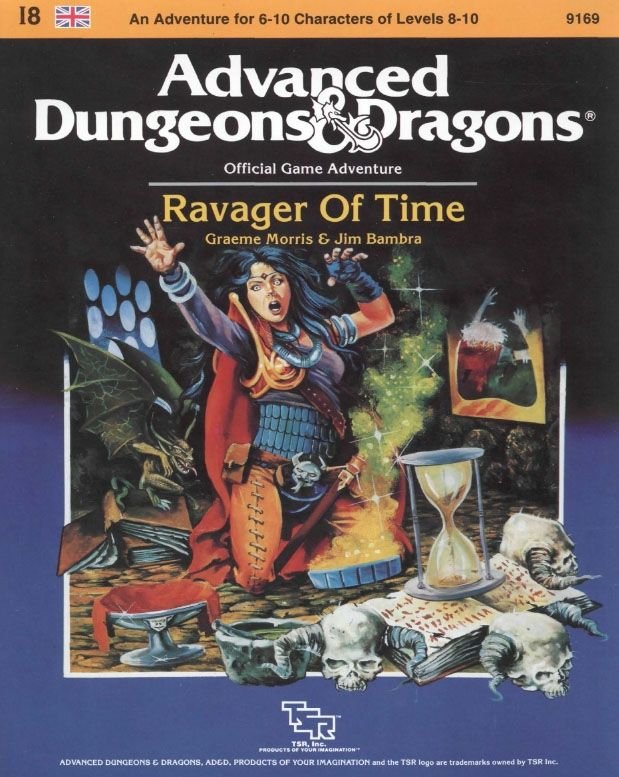

By 1977 Dungeons & Dragons had split into two branches: basic D&D which would feel familiar to anyone who played board games, and the rule-heavy Advanced D&D for the more serious gamer who enjoys calculating THAC0 with a 20 sided dice.

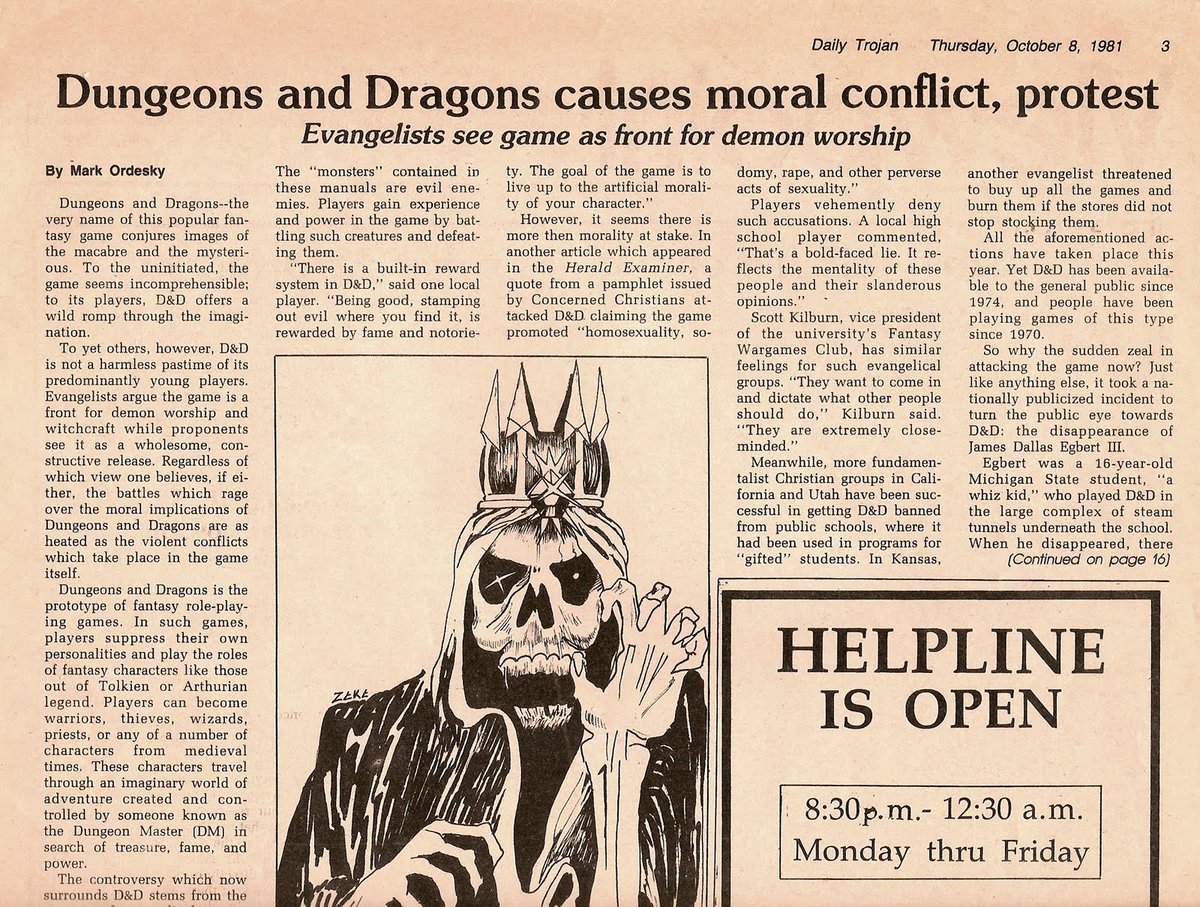

The boom in Dungeons & Dragons coincided with the 'Satanic Panic' of the early 1980s. The game was denounced by some evangelical groups for apparently promoting witchcraft and demon worship.

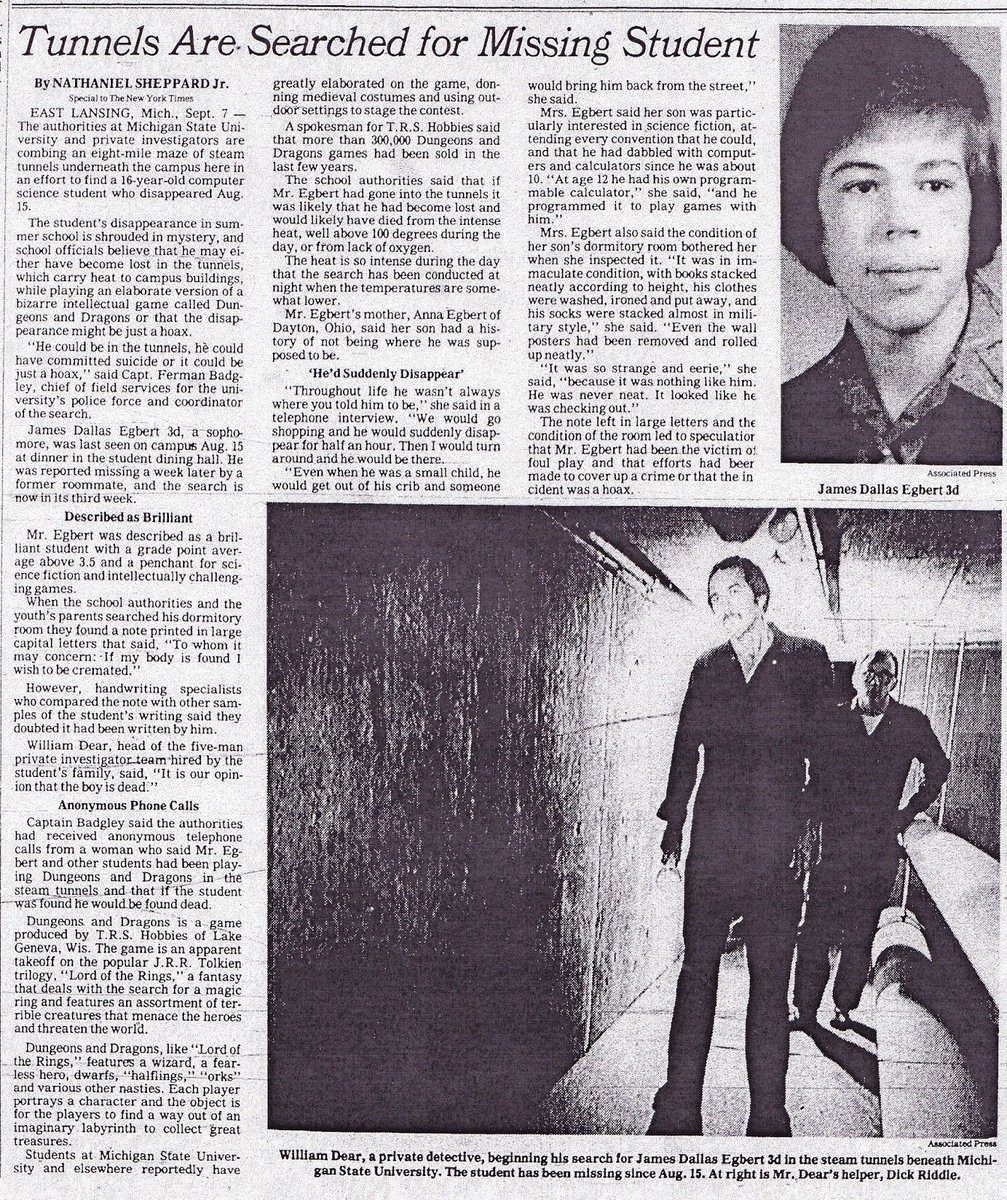

Part of the 'Satanic Panic' stemmed from the sensationalised story of the 1979 disappearance of Michigan student James Dallas Egbert lll. It was widely rumoured that he had been killed in a real-life Dungeons & Dragons game in the steam tunnels under his college.

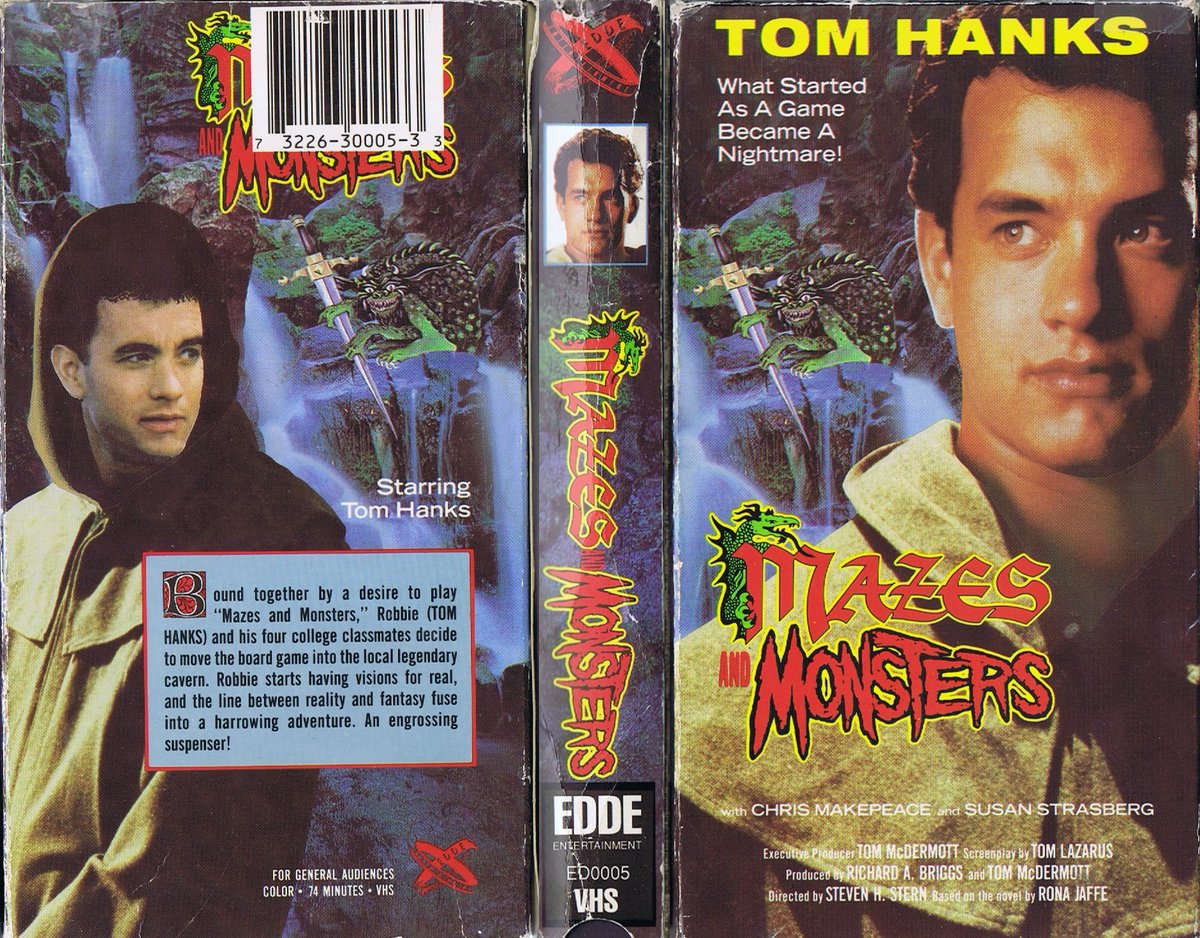

In fact Egbert had left Michigan after a failed suicide attempt, but the story that he had been killed playing Dungeons & Dragons for real was widespread. 'Mazes and Monsters', a 1981 novel later made into a Tom Hanks movie, was loosely based on the Egbert myth.

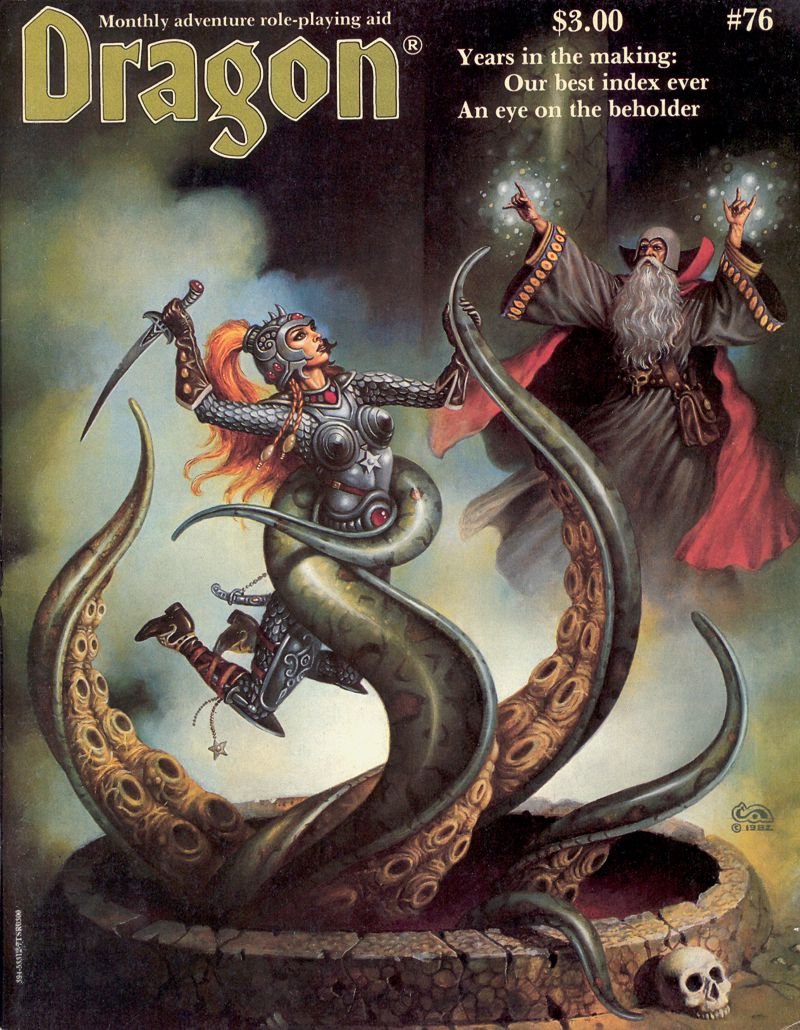

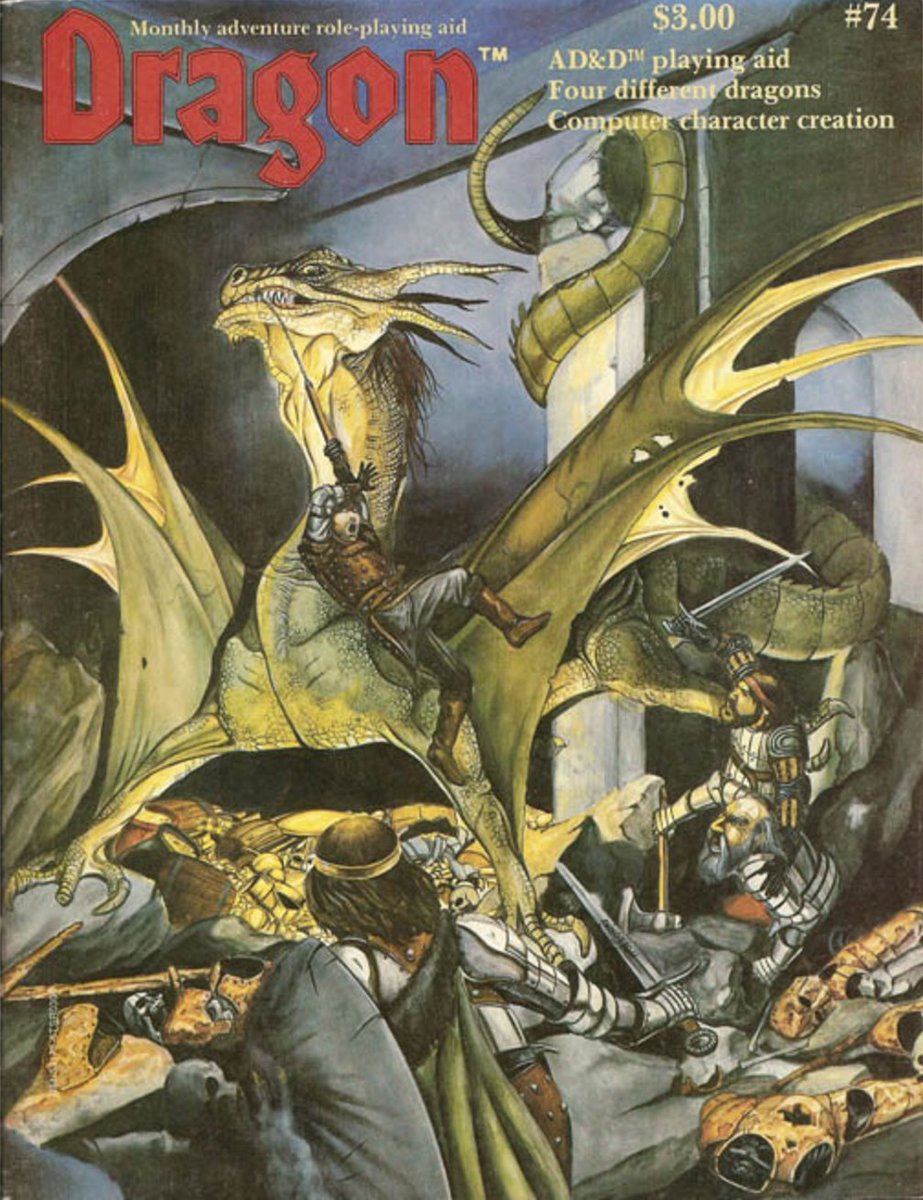

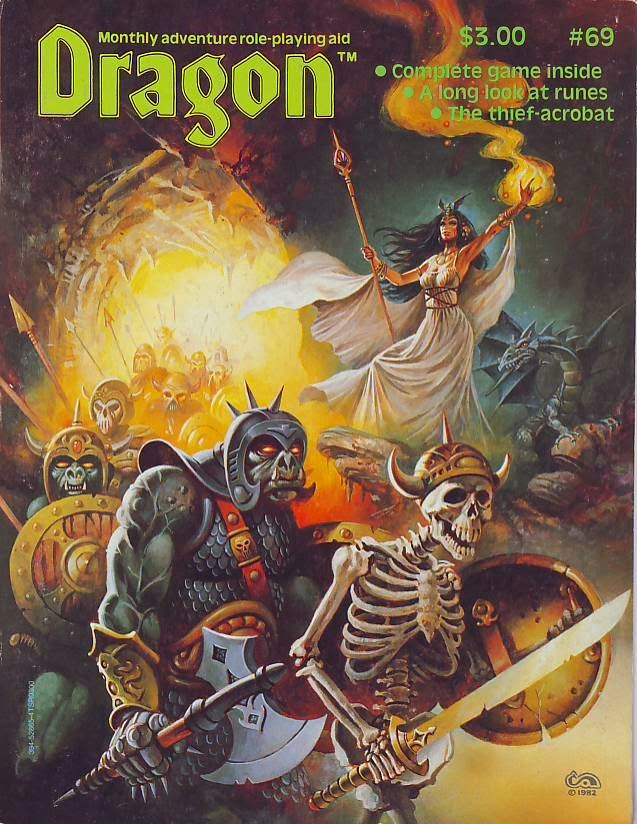

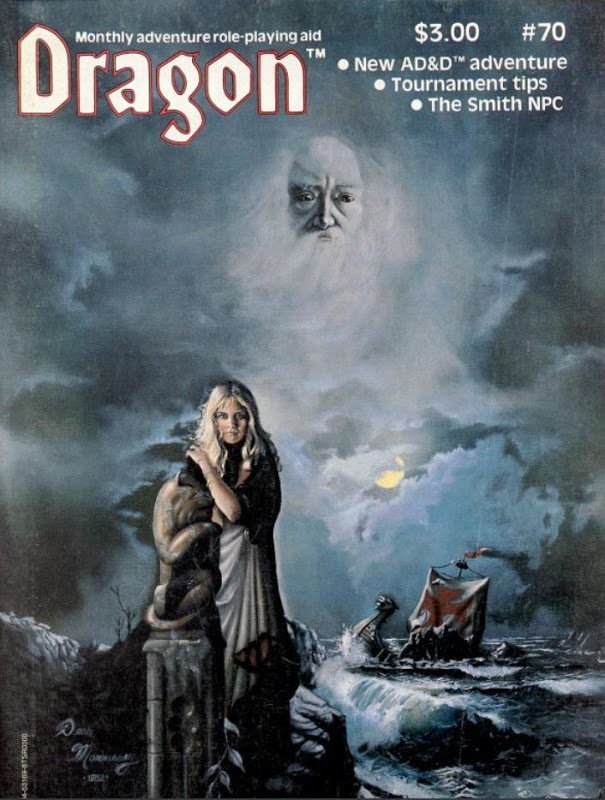

Whatever the reasons, Dungeons & Dragons sales boomed in the early '80s. TSR made $22 million in 1982 and its monthly magazine 'Dragon' was selling 100,000 copies by 1983.

But then the boom petered out: profits stalled, layoffs ensued.

But then the boom petered out: profits stalled, layoffs ensued.

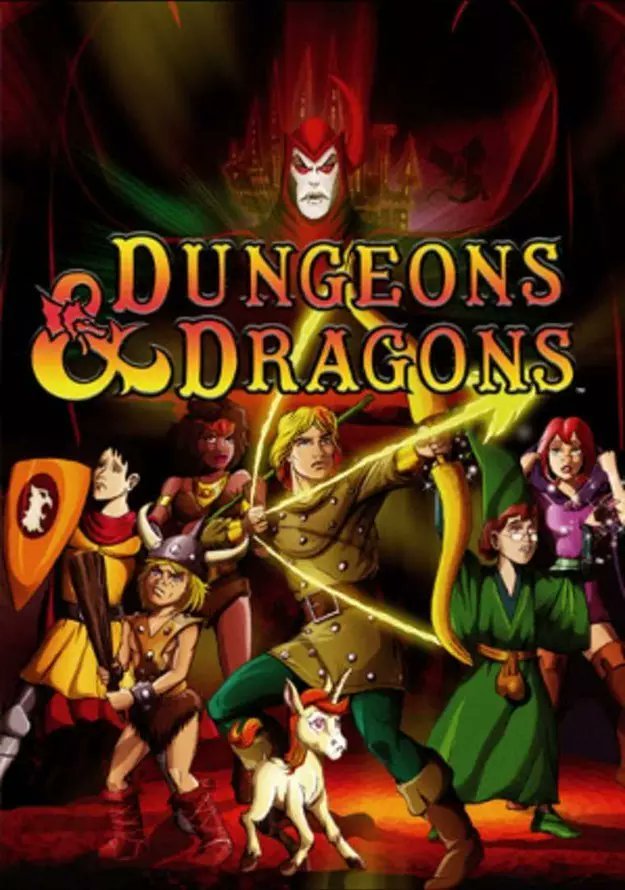

Gary Gygax was well aware that the Dungeons & Dragons name was worth more than the revenue from games alone. He wanted to diversify the brand into movies, books and software. So in 1983 he stepped back from games design to lead the new TSR Entertainment Corporation.

Gygax's diversification strategy seemed to pay off in 1983 when CBS premiered its Dungeons & Dragons animated TV series. However it wasn't enough to drive up games sales. By 1984 hundreds of TSR staff had been laid off, and profits were still projected to fall.

In 1985, at an acrimonious board meeting, Gary Gygax was ousted from the board of TSR. Lawsuits followed about the sale of shares that led to him losing the balance of power at the company, but in the end Gygax left.

TSR continued as an independent company for another 12 years after Gygax left, but by the mid 1990s it had fallen behind its competitors. It was acquired by Wizards of the Coast in 1997, and by 2000 the TSR name was dropped from Dungeons and Dragons products.

Dungeons & Dragons still lives on and is still popular. But the story of TSR is a good example of what can happen to a start-up company that suddenly finds huge commercial success and tries to scale and diversify too quickly. As a business case study it's worth studying.

That's it for my look at the history of Dungeons & Dragons.

More stories (*rolls dice*) another time...

More stories (*rolls dice*) another time...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh