📉UNEVEN GROWTH📈– Automation’s Impact on Income and Wealth Inequality, w @ben_moll @pascualrpo

A brand new & improved version of our paper out today @nberpubs:

nber.org/papers/w28440?…

Main idea + key results (thread): 🤖🧵

(tagging some whose great work we draw on🙏)

A brand new & improved version of our paper out today @nberpubs:

nber.org/papers/w28440?…

Main idea + key results (thread): 🤖🧵

(tagging some whose great work we draw on🙏)

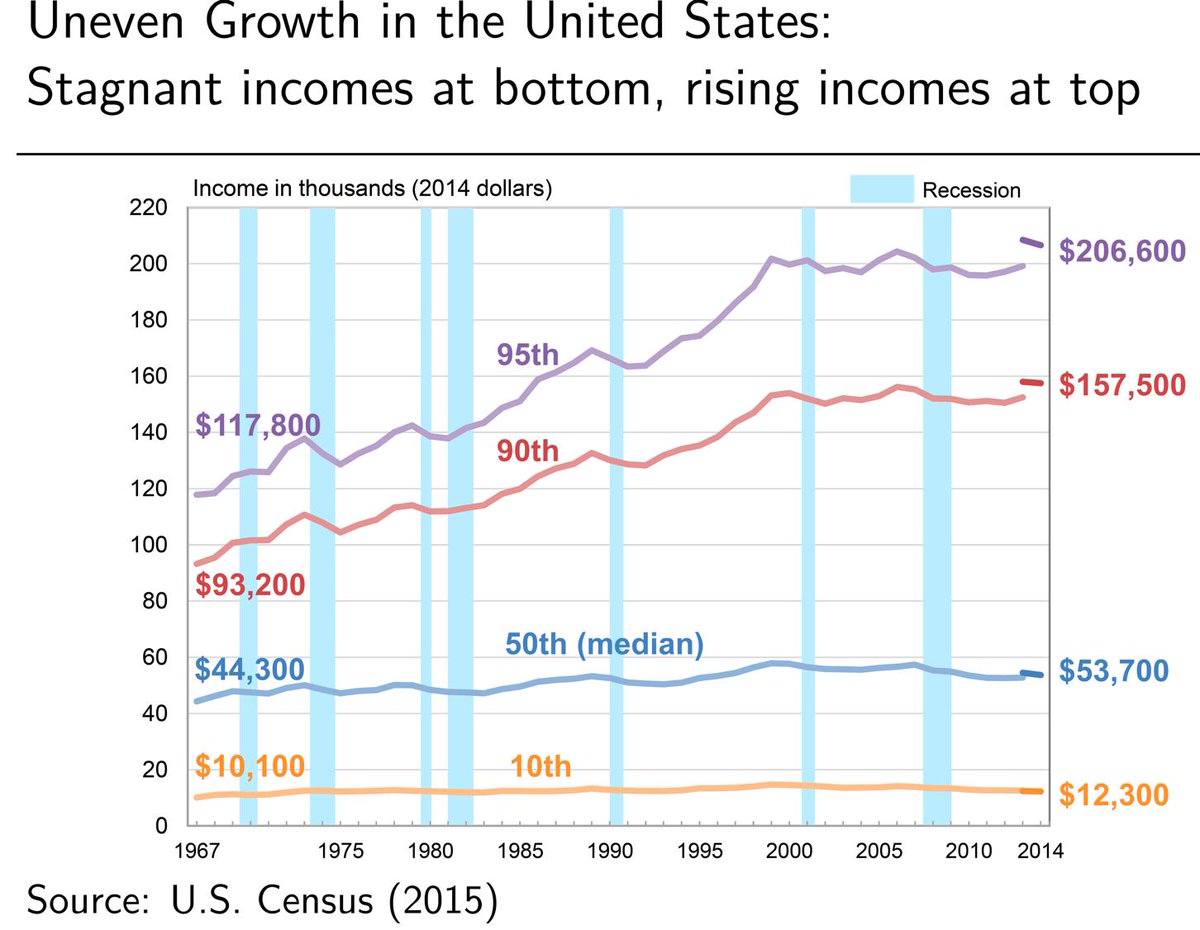

What are the distributional consequences of shifts in technology? Who wins and who loses, and why?

Much has been said about the uneven impact of technology on wages of different workers (@davidautor, @lkatz42).

Much has been said about the uneven impact of technology on wages of different workers (@davidautor, @lkatz42).

But what about its effects on wealth ownership and the unequal distribution of capital income?

In this paper we build a tractable framework of wealth and total (i.e. labor + capital) income distributions, and we use it to study the consequences of automation technologies.

In this paper we build a tractable framework of wealth and total (i.e. labor + capital) income distributions, and we use it to study the consequences of automation technologies.

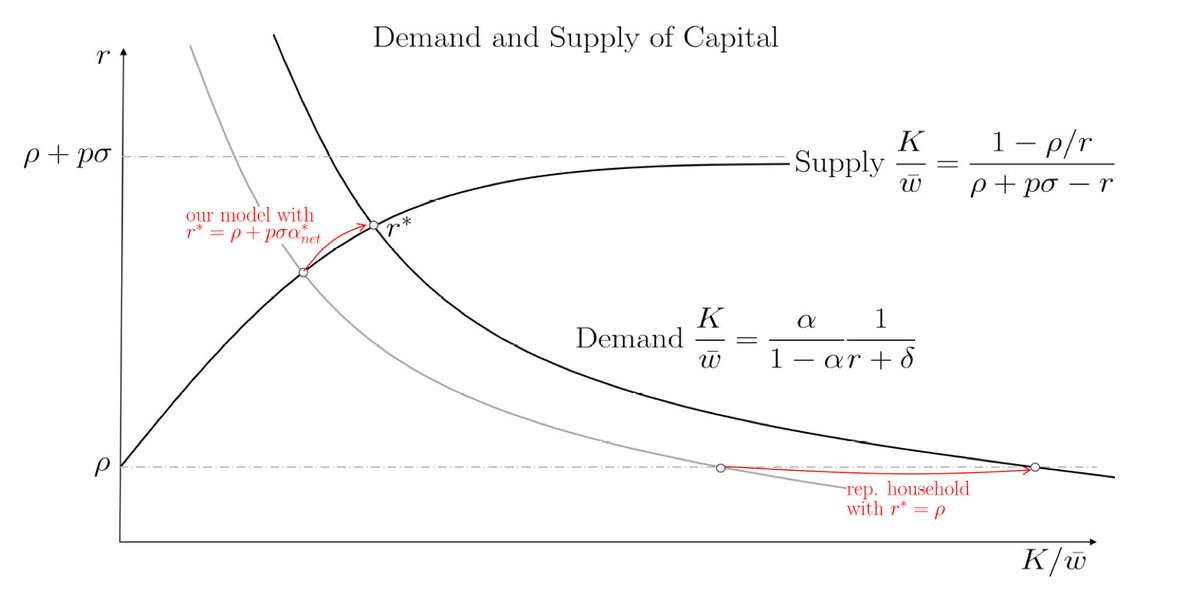

Our baseline model assumes that individual wealth accumulation processes can be interrupted, e.g. by death (@ojblanchard1), poor investment decisions (@albertobisin , @BenhabibJess), or a sudden urge to consume much of the accumulated wealth (@KrusellPer, Smith).

As a result the model features an upward-sloping capital supply and a fat-tailed distributions of income and wealth in equilibrium.

Automation allows producers to switch from labor to capital, *lowering* the demand for labor (the usual ‘displacement effect’ in @pascualrpo @DrDaronAcemoglu) and *raising* the demand for capital. This latter shift results in a higher return to wealth, even in the long-run.

At the individual level the higher return to wealth means fortunes grow more rapidly, and some people amass large holdings of wealth. This raises inequality. @ChadJonesEcon

This is the novel channel we isolate: automation ➡️ higher return to wealth ➡️ higher inequality.

This is the novel channel we isolate: automation ➡️ higher return to wealth ➡️ higher inequality.

The upshot is that some of the gains from technology accrue to capital owners (via higher returns) instead of workers. In our framework, wages may *fall* on average across the skill distribution (and in addition, relative wage differences across workers widen).

In a sense, our framework formalizes and extends @PikettyLeMonde's r-g intuition. Importantly it recognizes that r is determined endogenously in equilibrium, and that wages are affected by what happens to r.

Our extended model (w multiple assets, fin frictions, st st growth, mark-ups + taxes) sheds light on the diverging trends between the return to capital (stable or increasing) and safe real rate (declining) @LHSummers @FrancoisGourio @pogourinchas @R2Rsquared @kathrynholston

In the extended framework automation raises the return to capital but leaves the safe rate little changed, matching the rising wedge observed in the data.

We show that the theoretically-relevant return measure is the weighted average of the two rates with the weight on risky capital close to or even above 1 (if investors are levered). Premium over growth of such a relevant measure has increased over the decades.

In a model-meets-data exercise we conclude that the increase in inequality due to automation amounts to around ¾ of the observed increase in top income inequality in the US documented by @PikettyLeMonde Saez @gabriel_zucman

Capital income is crucial, particularly at the top.

Capital income is crucial, particularly at the top.

The framework is well-suited for analyses of aggregate and distributional consequences of other technologies and a broader set of phenomena. It may also be useful for thinking about optimal taxation of capital income and wealth @ludwigstraub @IvanWerning

Thanks for reading!

Thanks for reading!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh