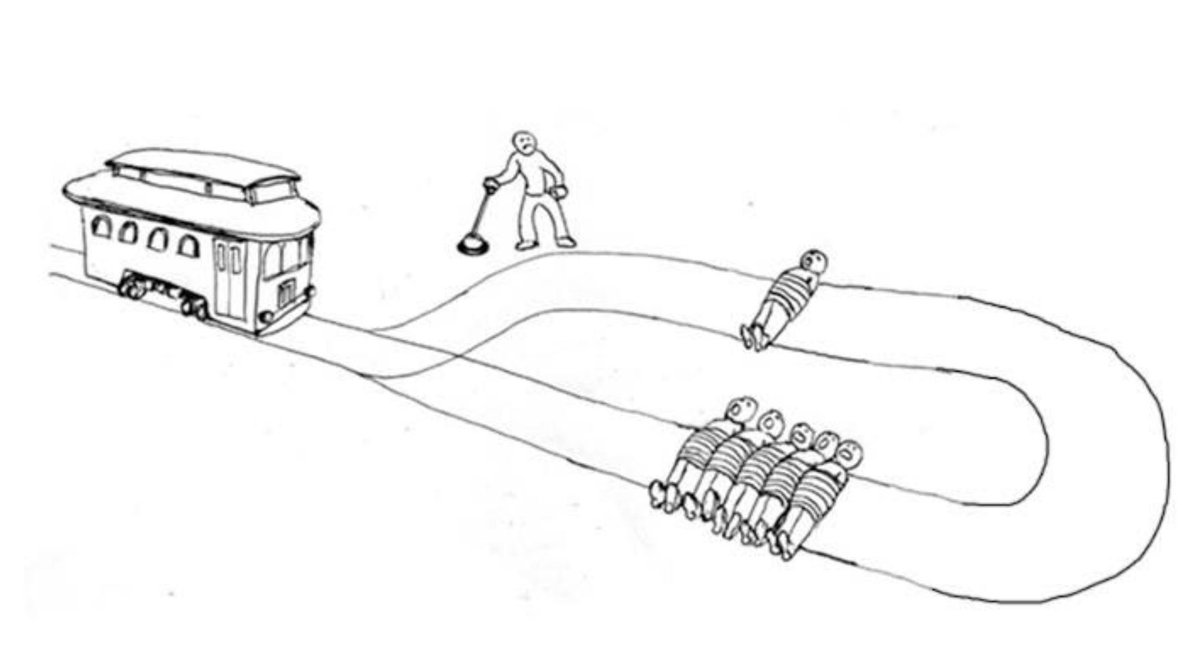

TROLLEY PROBLEMS We spend too much time on deciding which way to pull the lever, and not nearly enough time on slowing trolleys down and asking ourselves "why are there people bound to the tracks"?

Thread with examples, 1/N

Thread with examples, 1/N

2/ One example: should Trump be banned? Was the election stolen?

These are lever questions.

The trolley question is: how come fraud and/or "changing the rules at the last minute" are plausible?

These are lever questions.

The trolley question is: how come fraud and/or "changing the rules at the last minute" are plausible?

3/ It's important to focus on trolley questions, because pulling a lever doesn't stop the trolley – it will keep being a problem in the future.

4/ Another example: COVID.

The lever question: save lives or livelihoods?

The trolley question (back in early 2020): how do we prevent the spread? Ground planes, wear face masks immediately, etc.

The trolley question is what prevents the leverquestion, which is a lose-lose.

The lever question: save lives or livelihoods?

The trolley question (back in early 2020): how do we prevent the spread? Ground planes, wear face masks immediately, etc.

The trolley question is what prevents the leverquestion, which is a lose-lose.

5/ Another example: student debt.

The lever question: do we forgive debt or not?

The trolley question: how come that some degrees are not a profitable investment anymore? Why do they cost so much or deliver so little value, that people cannot easily repay their debt?

The lever question: do we forgive debt or not?

The trolley question: how come that some degrees are not a profitable investment anymore? Why do they cost so much or deliver so little value, that people cannot easily repay their debt?

6/ Yes, the lever problem is more urgent.

But addressing the trolley problem is more important.

Otherwise we'll keep facing lose-lose situations.

We can't play by the problem's agenda.

We can work on the important before it becomes urgent.

But addressing the trolley problem is more important.

Otherwise we'll keep facing lose-lose situations.

We can't play by the problem's agenda.

We can work on the important before it becomes urgent.

7/ 🎯 The utilitarian calculus restricts us to think about the current instance of the problem only.

When you have a plausibly repeating problem, it doesn’t make sense. The root must be addressed. With urgency.

When you have a plausibly repeating problem, it doesn’t make sense. The root must be addressed. With urgency.

https://twitter.com/diomavro/status/1364149103542861824

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh