Some observations on the Biden administration's response to recent attacks in Erbil and Baghdad, including last night's airstrike in Syria—all of which reflect a much needed return to a more considered and sustainable Iraq policy. ...

defense.gov/Explore/News/A…

defense.gov/Explore/News/A…

Threats from Iran-backed militias are a deadly reality for U.S. personnel in Iraq, and will be for the foreseeable future.

But how the United States deals with these threats has major ramifications for the bilateral relationship, and other U.S. interests there.

But how the United States deals with these threats has major ramifications for the bilateral relationship, and other U.S. interests there.

The Biden administration is clearly making it a priority to maintain and restore the conditions allowing for the U.S. and Coalition military presence in Iraq.

That's a good thing legally and politically, and a necessary corrective from the Trump administration's policies.

That's a good thing legally and politically, and a necessary corrective from the Trump administration's policies.

These forces are in Iraq at its invitation to combat ISIS and train and equip its troops.

That's an important mission, because a stronger Iraq will be better equipped to deal with internal instability and limit Iranian imposition, including via militias.

(More on this below.)

That's an important mission, because a stronger Iraq will be better equipped to deal with internal instability and limit Iranian imposition, including via militias.

But Iraqi consent doesn't come easy. For many Iraqis, U.S. military activity in Iraq hearkens back to the post-2003 occupation. Iran and other U.S. rivals play up these anxieties for their own interest.

As a result, U.S. military action often ends up being controversial.

As a result, U.S. military action often ends up being controversial.

(This can also be true Iranian interference in Iraq, including Iran-backed militias, which many Iraqis see as criminal gangs or worse.

But Iran's historical ties to Iraq give it reservoirs of support that the U.S. can't compete with, including in the governing Shi'a coalition.)

But Iran's historical ties to Iraq give it reservoirs of support that the U.S. can't compete with, including in the governing Shi'a coalition.)

This is why the Biden admin has so far been careful to move slowly and coordinate its response to recent attacks with the Iraqis, as last night's DOD statement emphasizes.

It's also most likely why the eventual military response took place in Syria, not Iraq.

It's also most likely why the eventual military response took place in Syria, not Iraq.

By contrast, the Trump administration tried to deter Iran and the militias they back (but don't always control) by drawing red lines and responding quickly in kind in both Iraq and Syria, even over the open objections of Iraqi officials.

Unsurprisingly, this caused problems.

Unsurprisingly, this caused problems.

In response, Iraqi officials made repeated public requests that U.S. forces move towards withdrawal. Its parliament voted to that effect, albeit non-bindingly.

The Trump administration's response that it might stay in Iraq even without its consent only made things worse.

The Trump administration's response that it might stay in Iraq even without its consent only made things worse.

(Generously, they may have been referring to the continuation of cross-border operations on counter-ISIS targets. But that'd be a different, narrower, and less ambitious mission.

It's rare you can train, equip, and support foreign troops who see you as a hostile intervenor.)

It's rare you can train, equip, and support foreign troops who see you as a hostile intervenor.)

The fact that Iraq never cut the cord reflects the continued support for U.S.-Iraq cooperation among Iraqi leaders, as well as Iran's own overreach.

But these actions put a lot of pressure on these officials. And eventually they were going to break.

But these actions put a lot of pressure on these officials. And eventually they were going to break.

The Trump administration didn't seem too concerned about this. I suspect this in part reflects the fact that they didn't actually value the Iraq mission, and gave far higher priority to putting pressure on Iran, towards no particular end.

But that's a real mistake.

But that's a real mistake.

Airstrikes can hurt militias' operational capacity, but can't uproot or constrain their ability to operate on the ground in Iraq.

To do that, you need to strengthen conventional Iraqi security forces so they can realistically push back.

To do that, you need to strengthen conventional Iraqi security forces so they can realistically push back.

A stronger Iraq can also counterbalance Iran as a whole.

While the two neighbors will always have close economic and cultural ties, plenty of Iraqis resent the violence and corruption that Iran uses to interfere in their country.

While the two neighbors will always have close economic and cultural ties, plenty of Iraqis resent the violence and corruption that Iran uses to interfere in their country.

U.S. and Coalition support can be a big part of this.

But every time the Trump administration openly pursued an airstrike over Iraqi objections, it undermined the domestic legal and political support necessary for that effort.

But every time the Trump administration openly pursued an airstrike over Iraqi objections, it undermined the domestic legal and political support necessary for that effort.

It also helped to justify the militias' own violent activities, which often kill Iraqis at a higher rate than Americans.

This in turn weakened the case for Iraqi officials' efforts to contain them, and made it easier for rivals to paint them and the U.S. as moral equivalents.

This in turn weakened the case for Iraqi officials' efforts to contain them, and made it easier for rivals to paint them and the U.S. as moral equivalents.

As I've argued for the past four years, to succeed in Iraq, the U.S. has to make the strongest case possible that it is a genuine partner and ally of the Iraqis.

This means working with them against threats, not unilaterally over their objections.

This means working with them against threats, not unilaterally over their objections.

If the U.S. really feels that it must act without Iraqi support, then it must have a strong legal and policy basis for doing so and make clear to Iraqis that it is only doing so as an absolute last resort.

And then prepare for the political consequences, which will be real.

And then prepare for the political consequences, which will be real.

This approach always requires concerted and difficult diplomacy. Often the immediate results will be less than satisfactory. And yes, it requires risks to U.S. personnel that can be very hard to swallow.

But in the long run, it's the only way to succeed at the current mission.

But in the long run, it's the only way to succeed at the current mission.

Some will no doubt argue that this mission isn't likely to succeed or isn't worth the risk. And maybe they're right.

But if that's the case, then the right path is to pare down the mission or to leave, not to pretend that the U.S. can accomplish its goals without Iraqis onboard.

But if that's the case, then the right path is to pare down the mission or to leave, not to pretend that the U.S. can accomplish its goals without Iraqis onboard.

This is the direction that I see the Biden administration headed towards, and I think it's a good one.

Of course, it also has good synergy with the diplomatic effort to reengage with Iran over the JCPOA, as it seeks to reduce tensions and return to a 2016-era detente.

Of course, it also has good synergy with the diplomatic effort to reengage with Iran over the JCPOA, as it seeks to reduce tensions and return to a 2016-era detente.

This also opens new opportunities for pressuring powerful militias like KH and AAH in Iraq, which remain an immense challenge.

While backed by Iran, they're not entirely in its control. And if their actions begin to derail negotiations with the U.S., they may become a liability.

While backed by Iran, they're not entirely in its control. And if their actions begin to derail negotiations with the U.S., they may become a liability.

In this sense, working cooperatively with the Iraqis and engaging diplomatically with Iran can isolate such groups from both ends, and create more political space for containing them.

Notably, last night's airstrike is arguably the least important part of this strategy.

Much more important is what the Biden administration chose not to do, and how it went about doing what it did do—both of which are a sharp contrast with its predecessor.

Much more important is what the Biden administration chose not to do, and how it went about doing what it did do—both of which are a sharp contrast with its predecessor.

There is an unfortunate drive in U.S. policymaking to want to meet force with force, and to always see that as the right solution.

But in Iraq, giving in to this instinct often undermines the actual long-term mission.

But in Iraq, giving in to this instinct often undermines the actual long-term mission.

I don’t know enough about the facts of last night’s strike to evaluate whether it really made sense.

There’s a real possibility it was primarily a response to domestic political pressures, which is never a good reason.

There’s a real possibility it was primarily a response to domestic political pressures, which is never a good reason.

But I am encouraged the Biden administration, if it had to act, chose to do so in a way that the Iraqi gov’t at least seems unlikely to openly oppose, and did so after extensive consultations and careful deliberation.

That’s the right path forward.

That’s the right path forward.

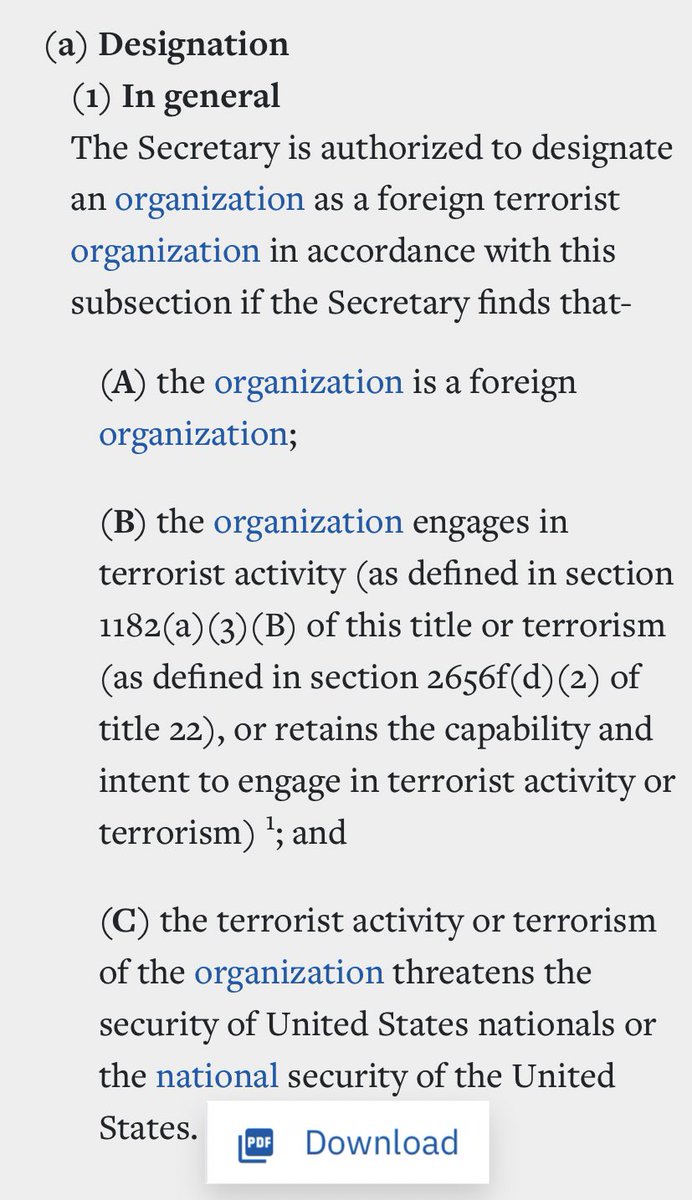

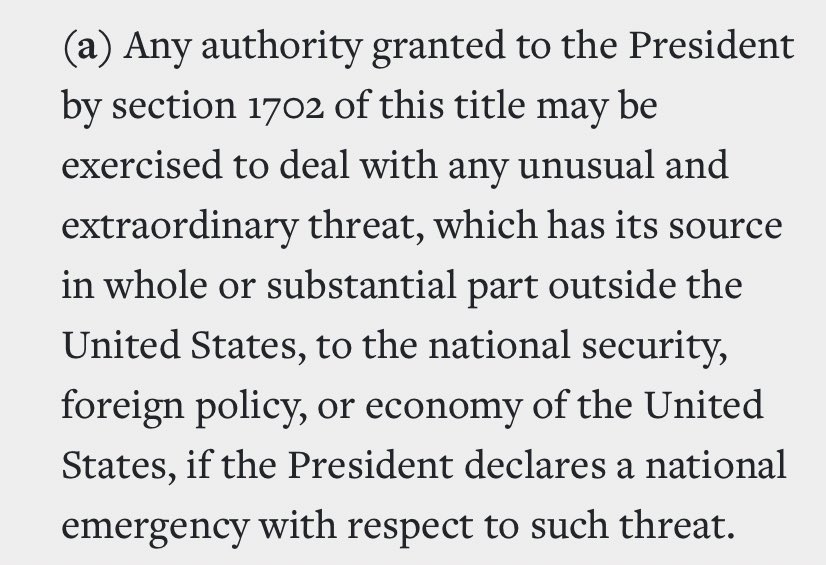

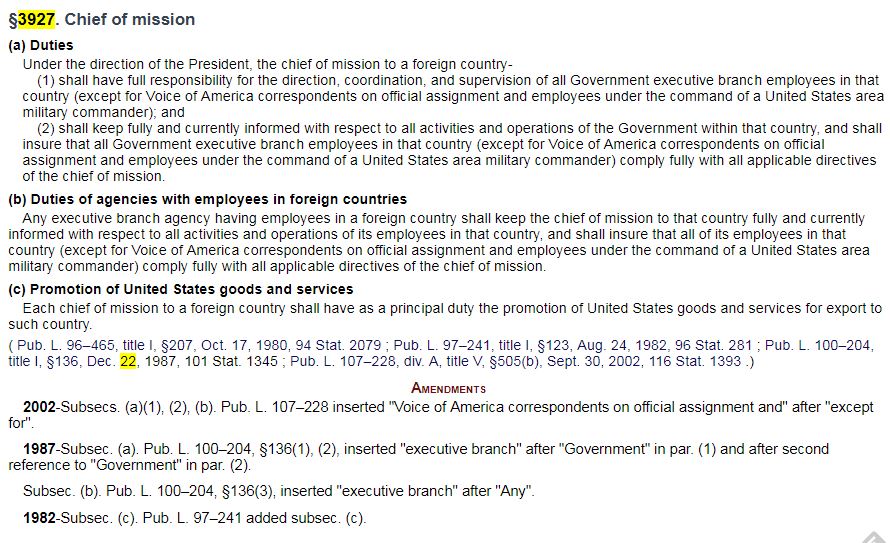

(Separately, last night's airstrike of course implicates all sort of domestic and international legal questions relating to war powers.

I'm hoping to tackle those in a separate thread in a bit.)

I'm hoping to tackle those in a separate thread in a bit.)

Note: I wrote about the complicated dynamics around the U.S. approach to Iraq for @lawfareblog after the airstrikes in Dec. 2019, and a lot of it still applies today.

Check it out if you want some more elaboration on the legal and political considerations

lawfareblog.com/law-and-conseq…

Check it out if you want some more elaboration on the legal and political considerations

lawfareblog.com/law-and-conseq…

And here is the promised thread on war powers issues, for those interested:

https://twitter.com/S_R_Anders/status/1365403190729007106?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh