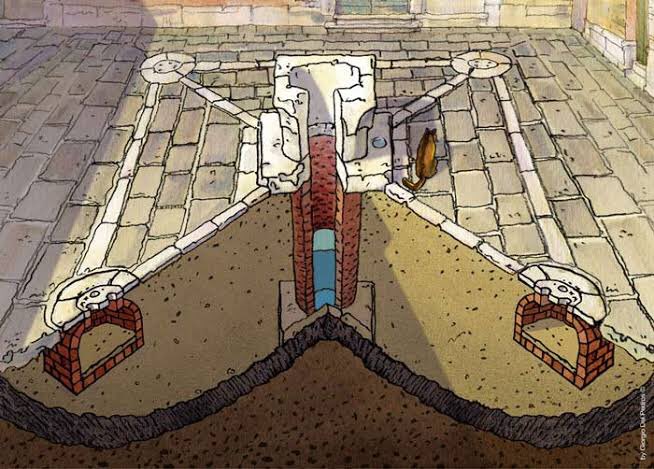

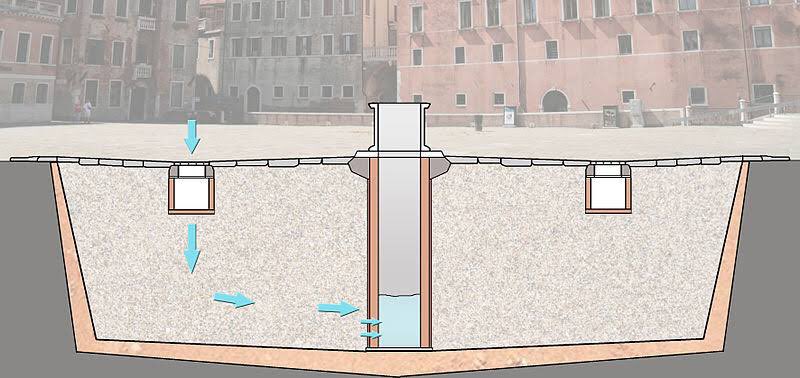

The Venetian Well is a clever way to collect and clean rainwater for household use in dense urban areas without usable groundwater or nearby springs, such as on rocky islands or reclaimed land. The name comes from the technique having been the principal way Venice got its water.

A square or courtyard—the bigger the better but any size works—is dug out to a depth of six meters, filled with sand and gravel, one or more drains are installed to collect rainwater which is then allowed to filter down to the bottom and seep into the well made of porous brick.

Naturally a construction of this size and complexity was a huge undertaking and could only be accomplished collectively. The Venetian Republic cooperated with private sponsors to install over 6000 of these wells from the late middle ages to the end of the 18th century.

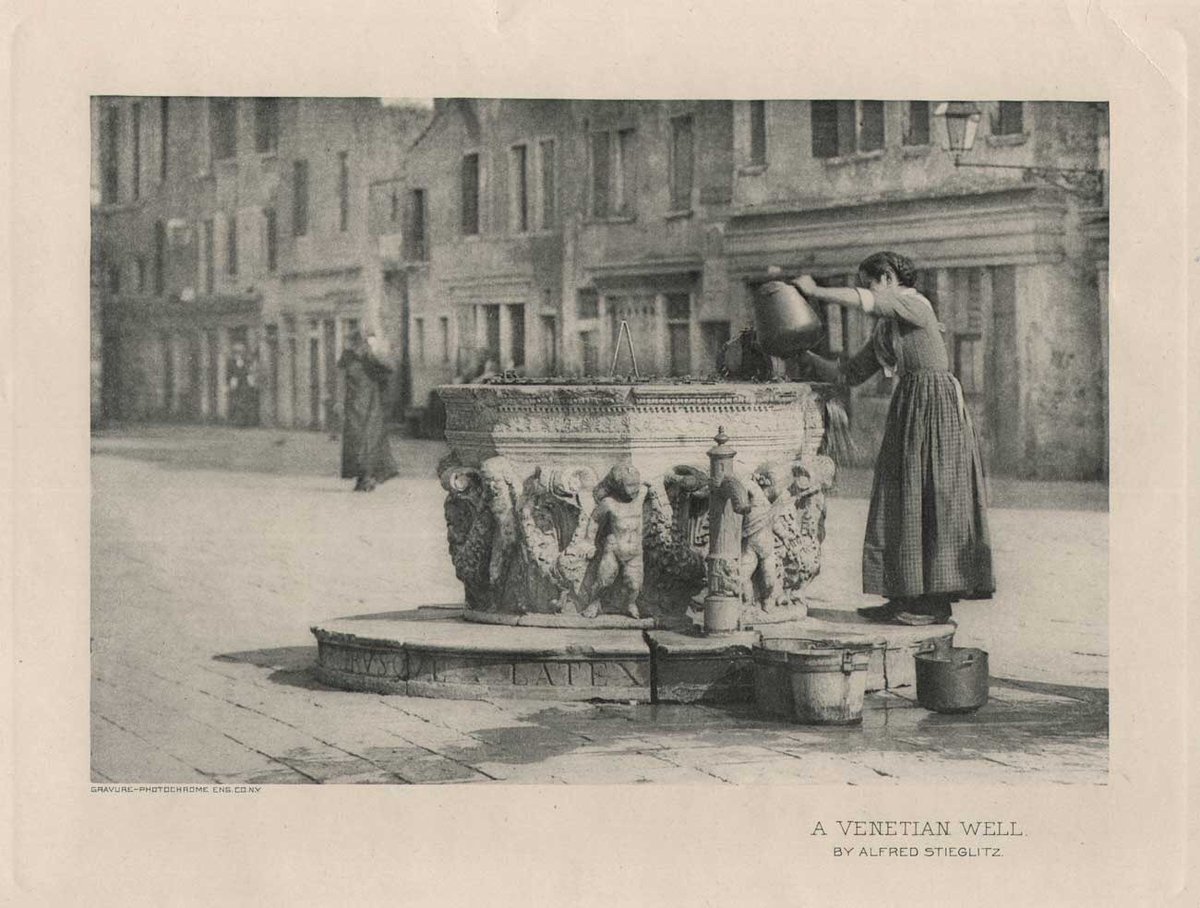

The wells were provided with highly decorated well heads, originally often recycled Roman capitals, but later on specifically designed to glorify the sponsors of the well construction. These were a huge hit with wealthy Europeans and many were exported in the late 19th century.

The well was crucial to make life in Venice possible, so a detailed system to protect and care for them was devised, locks were installed and they were only opened during specific times: announced by a bell rung by the lock keeper (often a parish priest), and again at closing.

The Venetian lack of water was also the main reason you seldom saw street trees or private orchards in the courtyards: water was far too precious to use for trees, and the space was better used to catch and purify rain water.

Venetian Wells had a major drawback though: they were vulnerable to infiltration by surrounding water, which in the case of Venice meant sea water or polluted water. A flooding event could mean the well was out of operation for many months: in the meantime water was boated in.

Nevertheless, until Venice started suffering from acute overcrowding in the 19th century, the wells worked fantastically. They were even adopted in other cities where clean water was hard to get at, some even survive, like this famous well in Corfu, Greece.

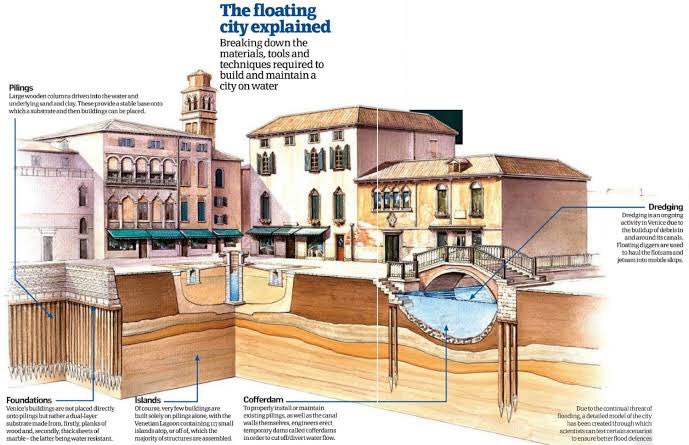

Until overpopulation, Venice was known throughout Europe as a healthy city, not least because of its clean drinking water but also because of its effective tide powered sewage system that would clean out the channels and canals twice a day: “l’aqua va in mar, il mar va in aqua.”

The wells even left a lasting imprint on the city itself: the many small open spaces needed to keep Venice with fresh water meant that the city became for more "open" compared to other contemporary Italian cities such as Bologna or Florence, whom could afford to build tighter.

The to go to image of Venice is the 1500 bird's eye map, created as a woodcut print by Jacopo de’ Barbari in Nuremburg, on the largest sheets of paper in Europe at its time. Best studied close up.

The average inhabitant in the 16th c. used 5 to 5.5 liters of water per day. In the 17th c. more wells meant the amount of available water had risen to 6.8 liters. Today the average Venetian (via the new 19th c. aqueduct) uses 300 to 350 liters of water per day.

The Venetian Well might have some of its roots in the Roman impluvium. Here's a thread on an older water harvesting system:

https://twitter.com/wrathofgnon/status/1019056740128600065

Some of the inspiration and one of the illustrations for this thread came from the book Venice the Basics by Giorgio Gianghian, Paolo Pavanini and illustrated by Giorgio Del Pedros, 2010. An excellent (short) easy to understand book on Venetian urbanism.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh