Forget everything you're reading about what's happening in Washington DC, or Brussels, or London, or Glasgow.

The most important event in years to determine the fate of the global climate is happening in Beijing tomorrow:

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

The most important event in years to determine the fate of the global climate is happening in Beijing tomorrow:

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

That's when China's 14th Five Year Plan gets presented to the "two sessions" of its pseudo-parliament.

It's a hugely important document that will determine the direction of China's economy, from the largest to the smallest scales, until 2026.

bloomberg.com/news/articles/…

It's a hugely important document that will determine the direction of China's economy, from the largest to the smallest scales, until 2026.

bloomberg.com/news/articles/…

After Xi Jinping's pledge in September to hit peak emissions this decade and net zero by 2060, some of the most important detail will be what's announced on the climate front.

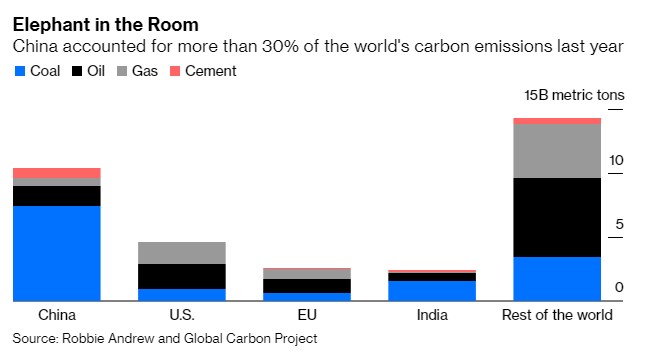

China last year accounted for more emissions than the U.S., European Union, and India *put together*.

China last year accounted for more emissions than the U.S., European Union, and India *put together*.

Without getting into a blame game, it's clear that unless China starts reining in emissions fast, efforts taken elsewhere in the world will be largely vain.

Global carbon budgets don't have enough wiggle room for a country with 30% of emissions to keep polluting at these rates.

Global carbon budgets don't have enough wiggle room for a country with 30% of emissions to keep polluting at these rates.

The good news is that Xi's net zero promise is a bold statement of intent.

The bad news is that there's strong domestic forces resisting this path.

The Five Year Plan is crucially important because it will shape the balance of power between these two sides over the years ahead.

The bad news is that there's strong domestic forces resisting this path.

The Five Year Plan is crucially important because it will shape the balance of power between these two sides over the years ahead.

Today I looked at four metrics you can look at to gauge the seriousness of the FYP. If we want to get serious about reducing emissions then a document setting out development plans to 2026 needs to start showing a pathway.

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

Firstly, renewable generation. Xi pledged in December that China would increase wind and solar capacity to 1,200 gigawatts by 2030, from 530GW last year.

That's certainly ambitious. There was about 1,400GW of wind and solar *globally* last year. But I think China can do better.

That's certainly ambitious. There was about 1,400GW of wind and solar *globally* last year. But I think China can do better.

Last year the country connected 120GW of wind and solar. There's a few queries about that very high figure, but the country's wind and solar industry bodies say they can roll out 115GW a year over the next five years, and more late in the decade.

greentechmedia.com/articles/read/…

greentechmedia.com/articles/read/…

At that pace you'd reach 1,100GW by 2025, not 1,200GW by 2030, and even with substantial growth in electricity demand coal-fired power would decline before 2025.

The risk of a lower figure is that (despite Xi's ("*over* 1,200GW" framing) it ends up treated as a sort of soft upper limit, rather than a baseline.

State Grid is planning to connect "more than 1,000GW" of wind and solar by 2030, but if that "more than" isn't substantially bigger than 1,000GW then there won't be sufficient power lines to deliver extra renewable electrons to end-users.

argusmedia.com/en/news/219189…

argusmedia.com/en/news/219189…

A bolder figure now gives all parties the political space and clear direction to increase their ambitions, so that China starts decarbonizing as fast as its industrial and technological might will allow.

Next metric:

Increase share of new-energy vehicles to 25% by 2025.

This is actually not that much more bold than already-announced policy. The governing State Council set a 20% by 2025 target last November: govt.chinadaily.com.cn/s/202011/03/WS…

Increase share of new-energy vehicles to 25% by 2025.

This is actually not that much more bold than already-announced policy. The governing State Council set a 20% by 2025 target last November: govt.chinadaily.com.cn/s/202011/03/WS…

And new-energy vehicles (mostly electric, but also including plug-in hybrid and a few fuel cells) made up 5.6% of sales last year, or 1.3 million vehicles:

spglobal.com/platts/en/mark…

spglobal.com/platts/en/mark…

At the same time, I suspect it may be the hardest target to hit. Because China's car market is so low-cost, the tipping points when electric vehicles hit price parity with conventional ones are likely to come much later in the decade than in richer countries.

The buyers in the car market are also overwhelmingly private, so government mandates, while important, aren't going to have quite as direct an impact as they do in the power and industrial sectors.

At the same time, there's clear non-climate reasons to be bold.

EVs play a key role in China's plans to upgrade its industrial sector.

75% of oil is imported, a security vulnerability which helps explain tensions in the South China Sea and OBR projects in Burma and Malaysia.

EVs play a key role in China's plans to upgrade its industrial sector.

75% of oil is imported, a security vulnerability which helps explain tensions in the South China Sea and OBR projects in Burma and Malaysia.

A 25% share may be a harder lift than the State Council's 20%, but given the number of European countries promising to phase out petrol and diesel altogether by 2030 or 2035 it's the sort of ambition that could spur the capacity expansions needed to stimulate the local EV sector.

Next: A 25% reduction in steel emissions by 2025, relative to 2020.

This really shouldn't be all that hard, IMO, because 2020 was a bumper steel year.

If China just reduces steel output to 2017 levels (which was seen as a boom year, at the time) it will be down 21% on 2020.

This really shouldn't be all that hard, IMO, because 2020 was a bumper steel year.

If China just reduces steel output to 2017 levels (which was seen as a boom year, at the time) it will be down 21% on 2020.

China is producing more and more scrap, and is already planning to increase the share of recycled electric-arc-furnace steel to 20% from 10% at present. Back of the envelope, that at a stroke wipes off 6%-8% of emissions.

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

Baowu, China's biggest steelmaker, is promising to go to net zero in 2050 and reduce emissions 30% by 2025.

That should be a benchmark. 25% should be achievable as the current extraordinary pandemic-related industrial stimulus is unwound.

bloomberg.com/professional/b…

That should be a benchmark. 25% should be achievable as the current extraordinary pandemic-related industrial stimulus is unwound.

bloomberg.com/professional/b…

Lastly, cement. If China's cement industry was a country, it would be the world's third-biggest emitter -- larger than Japan, Germany, the U.K. and France put together. The FYP should aim for a 20% reduction by 2025.

This again sounds quite ambitious, but it's not unprecedented. Cement output fell about 12% from 2014 to 2018 before edging back up.

Cement is a uniquely difficult industry to decarbonize. In power, the most competitive generation technologies in the world today are renewable.

Cement is a uniquely difficult industry to decarbonize. In power, the most competitive generation technologies in the world today are renewable.

In road transport, electric vehicles are competitive with high-end conventional ones and the entire industry is investing with an eye to EVs replacing petrol- and diesel-driven cars within a decade, or not much more.

In steel, electric secondary steel is already a dominant industry in countries like the U.S. and is likely to head that way in the coming years in places like China just because of rising scrap supply, even without help from climate policies.

In cement, though, there's no killer technology close to commercialization to replace the current, very dirty production method. You can use waste and biomass in kilns and change the ingredients of the clinker it's made out of, but these represent fairly marginal reductions.

Cement has one huge advantage, though: It's mostly bought by the state for major infrastructure projects, especially in a country like China which releases five-year economic plans. So the state can enforce purchase mandates much more easily than for, say, cars.

A "20% reduction by 2025" policy would leave SOEs, cement companies and builders to sort out the implementation. Maybe there's promising work do be done on kiln feed. Maybe they can make carbon capture work. Maybe they should switch to engineered wood.

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

Or maybe they should just *build less stuff*. China's industrial-stimulus development model keeps mounting up debt to build unproductive shiny assets and juice short-term GDP, and the government knows how much trouble it's storing up for itself.

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

Already in 2016, China's stock of public capital, per capita, was richer than that of Germany, South Korea, the U.K. -- far out of proportion to China's far lower per-capita income.

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

As @michaelxpettis has often warned, this just risks stirring up malinvestment and a future lost decade when China badly needs to be remaking its economic model to focus more on consumption, services and the developed lifestyle that Xi says is his goal for the nation.

@michaelxpettis I don't exactly expect to see any of these targets outlined in the FYP tomorrow -- although something a bit more modest seems probable.

To go beyond what Xi himself pledged last year would be politically dicey. But this is no time for timidity in climate ambitions.

To go beyond what Xi himself pledged last year would be politically dicey. But this is no time for timidity in climate ambitions.

@michaelxpettis That net zero announcement itself was a bold, unexpected move. As was Europe's "55% reduction by 2030" pledge. As is Biden's "zero carbon power by 2035" pledge. And all the other announcements we're now seeing.

@michaelxpettis If China's serious about reducing its emissions -- and thus improving the short-term health, and long-term climate fate of its 1.4 billion people -- it will be translating its long-term ambitions into short-term targets. Let's hope the detail matches up to the rhetoric. (ends)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh