Alright HOW ABOUT THIS:

an FND tour of the brain

(thread)

an FND tour of the brain

(thread)

Functional Neurological Disorder is a common (but not very well-known) brain disorder.

It can come with a variety of debilitating symptoms: tremors, seizures, paralysis, blindness or other visual disturbances, and pain, for starters. ⚡️

It can come with a variety of debilitating symptoms: tremors, seizures, paralysis, blindness or other visual disturbances, and pain, for starters. ⚡️

It’s a complex disorder and can be hard to understand. Doing so usually requires talking about how the brain works.

But what if we reversed that? Let’s use FND to introduce you to the brain.

But what if we reversed that? Let’s use FND to introduce you to the brain.

A quick note before we start: part of the reason it’s so hard to talk about the brain is that the brain works at levels both big and small. 🧠

Down at the micro level, you have brain cells doing things with proteins, firing electrical signals, and releasing neurotransmitters like dopamine.

Then there’s the level of “brain areas”, which are large enough to see with the naked eye. More on that in a sec.

These brain areas link together to create circuits, or larger groups called networks. We’ll mostly be talking about FND at the circuit- and area- level here. 👍

These brain areas link together to create circuits, or larger groups called networks. We’ll mostly be talking about FND at the circuit- and area- level here. 👍

And when you zoom 👀 all the way out, you see the brain as a whole organ, which is embedded the body, and which not only allows us to do physical things but also produces feelings, consciousness, and a feeling of selfhood.

Wow that was heavy. ANYWAY let’s get started! 😜

(very 2003 voice)

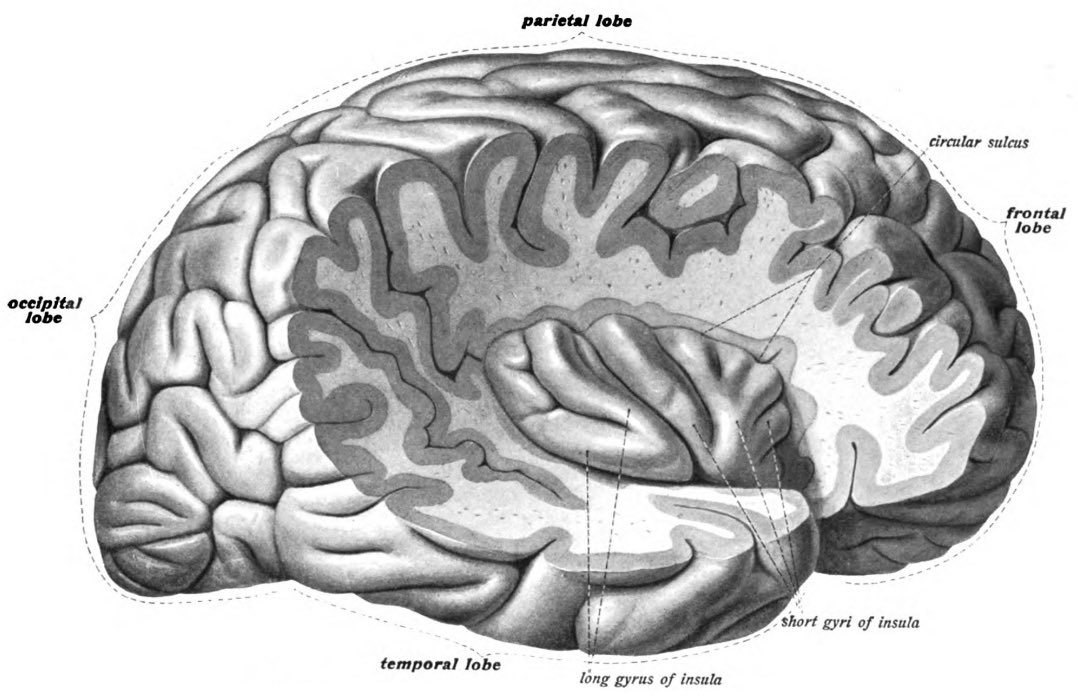

OK so. Here’s the brain. Chilling. Pretty sweet brain, you might say.

(very 2003 voice)

OK so. Here’s the brain. Chilling. Pretty sweet brain, you might say.

Like the earth, we can mentally divide up the brain into large chunks to specify what we’re looking at.

On the earth, they’re called continents.

In the brain, they’re called lobes.

On the earth, they’re called continents.

In the brain, they’re called lobes.

⬆️ Here’s the lobes of the brain. You don’t have to know what each one is called, just that they’re there.

Within each lobe are brain areas - some part of the brain that’s identifiably different from others.

They’re kinda like cities on a map.

You’ve probably heard of some, like the amygdala, or the hippocampus.

They’re kinda like cities on a map.

You’ve probably heard of some, like the amygdala, or the hippocampus.

What’s interesting is that brain areas don’t really do much on their own. They link together and communicate, and THAT’S how they get stuff done. These teams are called “circuits”, or at a larger scake “networks.”

Right, cool. But why should we care about all that? What are these brain areas and networks and lobes actually DOING?

Let’s use FND to investigate. 🧐🕵️🕵️♀️

Let’s use FND to investigate. 🧐🕵️🕵️♀️

Here’s a part of the brain called primary motor cortex, or M1.

When M1 is activated, it shoots signals down the spinal cord that cause you to move.

Here’s a weird map called a “homunculus” of what parts of M1 activate what muscles.

When M1 is activated, it shoots signals down the spinal cord that cause you to move.

Here’s a weird map called a “homunculus” of what parts of M1 activate what muscles.

Ok, so far so good. But the things humans do are more than simple twitches. We dance, drive, do yoga. Even typing and chess are complex, small moves.

How does that happen? One brain area won’t do it. You’ll need something more organized.

Like a hierarchy!

How does that happen? One brain area won’t do it. You’ll need something more organized.

Like a hierarchy!

That’s where the SMA (Supplementary Motor Area) comes in.

The SMA appears to be involved with planning more complex movements, and coordinating two-handed movements.

It appears to be the next step up the motor hierarchy, kind of like M1’s supervisor.

The SMA appears to be involved with planning more complex movements, and coordinating two-handed movements.

It appears to be the next step up the motor hierarchy, kind of like M1’s supervisor.

And that brings us to FND:

Several studies have shown differences in activation of the SMA in people w FND vs healthy people.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/P…

Several studies have shown differences in activation of the SMA in people w FND vs healthy people.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/P…

And that gets complicated because the SMA might also help produce feelings of “intentionality”: the feeling that you meant to make a movement

mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdfplus/10…

mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdfplus/10…

So if something were to go wrong with SMA, you’d expect to see two things common in FND: problems with movement planning, and a feeling that the unwanted movements don’t come from *you*, you didn’t mean to make them.

Let’s go one step higher up the motor chain before we really dig into the FND stuff specifically.

If SMA is M1’s supervisor, who supervises SMA?

That would be the prefrontal cortex (PFC), the much-celebrated home of logic and math and conscious thought in the brain, depending on who you believe.

That would be the prefrontal cortex (PFC), the much-celebrated home of logic and math and conscious thought in the brain, depending on who you believe.

PFC does seem to be involved in movement at a high level, like deciding what movements to make.

But there’s lots that’s still unknown here.

But there’s lots that’s still unknown here.

The important thing is that this hierarchy, from low to high, simple to complex, M1 -> SMA -> PFC, is replicated in many other systems of the brain too. 👍

Like eyesight! Visual processing follows a similar pattern:

It starts w very simple processing in the back of the brain (V1), passing through more complex steps along two paths until it reaches, surprise, PFC!

Weird, huh?

It starts w very simple processing in the back of the brain (V1), passing through more complex steps along two paths until it reaches, surprise, PFC!

Weird, huh?

It’s also worth noting that the current thinking is that this hierarchy works predictively.

That means the higher areas of hierarchy send out predictions about what they think should happen...

That means the higher areas of hierarchy send out predictions about what they think should happen...

... and the hierarchically lower brain areas (like V1) sending up info from the body that’s used to keep predictions in check.

Ostensibly, in FND the predictions become too strong and so can’t be easily corrected by the world - one reason why you might experience persistent visual phenomena or headaches that never go away.

The brain gets stuck on a predictive loop and refuses to update.

The brain gets stuck on a predictive loop and refuses to update.

Anyway, at some point all the different things the brain does: sensation, memory, thought, even the feeling of having a body, have to be knitted together *somehow* to construct the self that is you.

To be really clear, no one knows exactly how this happens.

But FND does appear to be a breakdown in this kind of process, which likely happens not at one place in the brain but through the interactions of networks, which could include areas like PFC.

But FND does appear to be a breakdown in this kind of process, which likely happens not at one place in the brain but through the interactions of networks, which could include areas like PFC.

But we know that FND isn’t intentionally produced, the way that the PFC might intentionally produce other movements and such.

After all, if we could stop the symptom, it wouldn’t be a problem! So what gives?

Where does the dysfunction in FND come from?

After all, if we could stop the symptom, it wouldn’t be a problem! So what gives?

Where does the dysfunction in FND come from?

We arrive now at the limbic system, the core system where much of the FND dysregulation has been found so far.

Traditionally, the limbic system was considered the “emotional” part of the brain.

Emotion scientists have recently (persuasively) argued that there’s much more to it, though.

Emotion scientists have recently (persuasively) argued that there’s much more to it, though.

Yes, these systems handle emotions. But they also govern important body-sensing and survival functions.

Thread on that here:

Thread on that here:

https://twitter.com/FndPortal/status/1126688702774665216

Take the insula, for example, my personal favorite brain area.

The back of the insula processes information from the body - heart rate, stomach fullness, muscle fatigue, all that stuff.

The back of the insula processes information from the body - heart rate, stomach fullness, muscle fatigue, all that stuff.

The middle part of the insula takes connections from other parts of the brain and sends them forward.

The front part of the insula seems to be involved in emotions, conscious awareness, and lofty things like that.

The front part of the insula seems to be involved in emotions, conscious awareness, and lofty things like that.

Which leads some scientists to think that the insula is kind of interpretively weaving our emotions out of body feelings, taking cues from the body about how we should feel.

nature.com/articles/nrn25…

nature.com/articles/nrn25…

The insula and other limbic areas are also part of central, core networks that handle a ton of the general information-processing in the brain!

So, not “just” emotional, then. But yes, emotions too.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/P…

So, not “just” emotional, then. But yes, emotions too.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/P…

Their functional and physical centrality make it possible for them to produce a variety of symptoms.

Because the problem in FND isnt just in the visual system, or the motor system. It’s in the connections between different capacities.

Because the problem in FND isnt just in the visual system, or the motor system. It’s in the connections between different capacities.

By the way, that front part of the insula? You guessed it: studies show alterations in some people w FND

jnnp.bmj.com/content/88/12/…

jnnp.bmj.com/content/88/12/…

Then there’s the TPJ, which has my vote for the spookiest brain area, 👻 and which is connected to the insula.

The TPJ seems to be important for maintaining a cohesive body-mind link.

The TPJ seems to be important for maintaining a cohesive body-mind link.

Damage to the TPJ can result in out-of-body experiences, or cause people to have trouble distinguishing between self and others

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15632275/

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15632275/

It will not surprise you to know: TPJ differences are also showing up in studies of FND!

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/P…

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/P…

So let’s start wrapping this thing up. We’ve talked about a bunch of brain areas affected in FND.

Is there any rhyme or reason to this?

What’s driving the motor symptoms, the pain, the over- and under-connection between brain areas + networks?

Is there any rhyme or reason to this?

What’s driving the motor symptoms, the pain, the over- and under-connection between brain areas + networks?

It’s time to introduce our final brain area: the amygdala.

Traditionally it was considered the brain’s “fear center”, but again experts have recently argued that it’s more about non-conscious threat processing; it doesn’t produce feelings of fear.

Traditionally it was considered the brain’s “fear center”, but again experts have recently argued that it’s more about non-conscious threat processing; it doesn’t produce feelings of fear.

Various studies have shown over-activity of the amygdala, as well as the amygdala sort of talking loudly (“over-connecting”) with other areas, including anterior insula and SMA.

Think about the ways FND is often triggered. Physical injuries, illness, emotional stress.

Do you always feel fear in all these situations? Not necessarily. But you might not have to, to get FND.

Do you always feel fear in all these situations? Not necessarily. But you might not have to, to get FND.

The amygdala operates outside of conscious awareness. If you’re in chronic pain, or have a sudden unexpected injury, the amygdala might boost its activity to a point where it disrupts other parts of the brain.

It can shout at the insula and SMA, which might both then disrupt motor stuff. And the insula might pass on the bad messages to TPJ and other brain areas, and then everything goes haywire.

And it can do that without *necessarily* triggering really conscious emotional distress (although that can happen sometimes.)

And it’s not really the amygdala’s fault. Threat processing is part of its job. It just gets a little too trigger-happy. 🤷🏻♂️

And it’s not really the amygdala’s fault. Threat processing is part of its job. It just gets a little too trigger-happy. 🤷🏻♂️

It’s important to note that no one knows FOR SURE that this is what’s happening.

But there’s a pile of evidence that suggests that this cloud of problems emerging from amygdala dysfunction is one way FND can happen.

But there’s a pile of evidence that suggests that this cloud of problems emerging from amygdala dysfunction is one way FND can happen.

We also don’t know is if this is the ONLY way, or if there are others as well.

When people with Parkinson’s develop FND secondarily, does that happen via the amygdala? Or something else?

Don’t think we know yet.

When people with Parkinson’s develop FND secondarily, does that happen via the amygdala? Or something else?

Don’t think we know yet.

But we do know that the FND brain is kind of stuck in a crisis.

So treatment for FND (and many other neuro conditions, as a wise physiotherapist recently noted) are about “calming shit down and building shit back up.” 😆

So treatment for FND (and many other neuro conditions, as a wise physiotherapist recently noted) are about “calming shit down and building shit back up.” 😆

The general idea is, however you got to FND, you want to calm the parts of the brain (probably including amygdala, insula, and sensory areas) that are likely helping drive symptoms.

and “build back” helpful relationships between the brain areas that aren’t communicating right. 👍

That’s one reason why @fndrecovery’s mirror work approach makes so much sense! It’s partly about supporting the brain to re-learn the body in a way it perceives as safe. 🙂

It’s also why the “biopsychosocial” concept of FND makes sense (at least to me): FND shows that “emotional” and “psychological” brain functions arise from circuits that *do a multitude of things*...

and hints as well that phenomena that might seem to be different in the brain, like:

⁃GABA neurotransmitter release

⁃anterior insula activation

⁃interoceptive awareness

can sometimes all be describing the same thing! just with the lens zoomed to different levels.

⁃GABA neurotransmitter release

⁃anterior insula activation

⁃interoceptive awareness

can sometimes all be describing the same thing! just with the lens zoomed to different levels.

So what’s the takeaway here?

It’s still early days for modern FND research, but the studies so far suggest that:

It’s still early days for modern FND research, but the studies so far suggest that:

⁃the brain is designed to keep us alive

⁃the brain might work via a hierarchical system of prediction

⁃emotions and attention help us prioritize what matters

⁃body and emotion are linked in the brain

⁃the brain might work via a hierarchical system of prediction

⁃emotions and attention help us prioritize what matters

⁃body and emotion are linked in the brain

⁃the amygdala might have the power necessary to push other brain areas off-balance

⁃a lot of that life-saving work the amygdala does happens outside conscious awareness

⁃and all your brain network activity somehow combines into a whole, which is “you”

⁃a lot of that life-saving work the amygdala does happens outside conscious awareness

⁃and all your brain network activity somehow combines into a whole, which is “you”

FND can be absolutely miserable. But it might also show us some really incredible things about how our brains work.

So there are that many reasons to study it. It’s vital to those of us that have FND, because we need help and want to live decent lives.

But it also might illuminate the scaffolding of the self for others who are curious enough to look. 👀

Thanks for reading along!

But it also might illuminate the scaffolding of the self for others who are curious enough to look. 👀

Thanks for reading along!

Want to learn more about FND?

Check out this short explainer by @jonstoneneuro at NORD

rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/…

And @fndhope’s excellent YouTube page

Follow any of the great patient orgs here (search “FND” and they should come up)

Check out this short explainer by @jonstoneneuro at NORD

rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/…

And @fndhope’s excellent YouTube page

Follow any of the great patient orgs here (search “FND” and they should come up)

and if you’re a med professional or researcher, check out @fndsociety!

(sorry about the end of the thread for early readers, I had to delete and start over 😫)

(sorry about the end of the thread for early readers, I had to delete and start over 😫)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh