Earlier this week I spoke at @thoracicrad about how biases affect our evaluations of performance. Here's the gist on how we measure "intelligence" and perceive others.

(I also talked about stereotypes but will save that for another day.)

1/

(I also talked about stereotypes but will save that for another day.)

1/

First of all, let's start with what intelligence is. There is a ton of variability, but this, from Howard Gardner, resonates with me.

2/

2/

How do we measure intelligence? There are many many many tests. What I learned about human cognitive abilities in my PhD, though, was there's no one measurable "intelligence." There are instead measures, such as the ones on this slide, of specific skillsets.

3/

3/

Using IQ tests maybe makes sense if you have a fixed mindset and believe everyone has a certain capacity and that's it. But Carol Dweck's work has shown the power of believing our capabilities are malleable and that we can grow.

4/

4/

Another thing that affects how we evaluate other people is the fundamental attribution error. "People are inclined to offer dispositional explanations for behavior instead of situational ones"

When we see someone DO something rude, we interpret them as BEING rude.

5/

When we see someone DO something rude, we interpret them as BEING rude.

5/

The person cutting you off on the freeway might be rushing someone to the hospital, for example. In other words, people are acting within the context of a situation. As Nisbett taught us, it's the person AND the situation that matter.

6/

6/

I'll summarize them briefly:

Halo effect: Someone does something good, you forever think they ARE good

Availability bias: You judge based on what is recent or most prominent in your mind rather than the overall performance

8/

Halo effect: Someone does something good, you forever think they ARE good

Availability bias: You judge based on what is recent or most prominent in your mind rather than the overall performance

8/

Confirmation bias: You interpret what you see in the way most consistent with what you expected

Unconscious bias: What we've seen/absorbed over time affects our unconscious judgments of others

In-group favoritism: We judge those who are like us more positively

9/

Unconscious bias: What we've seen/absorbed over time affects our unconscious judgments of others

In-group favoritism: We judge those who are like us more positively

9/

Negativity bias: The tendency to remember only negative things

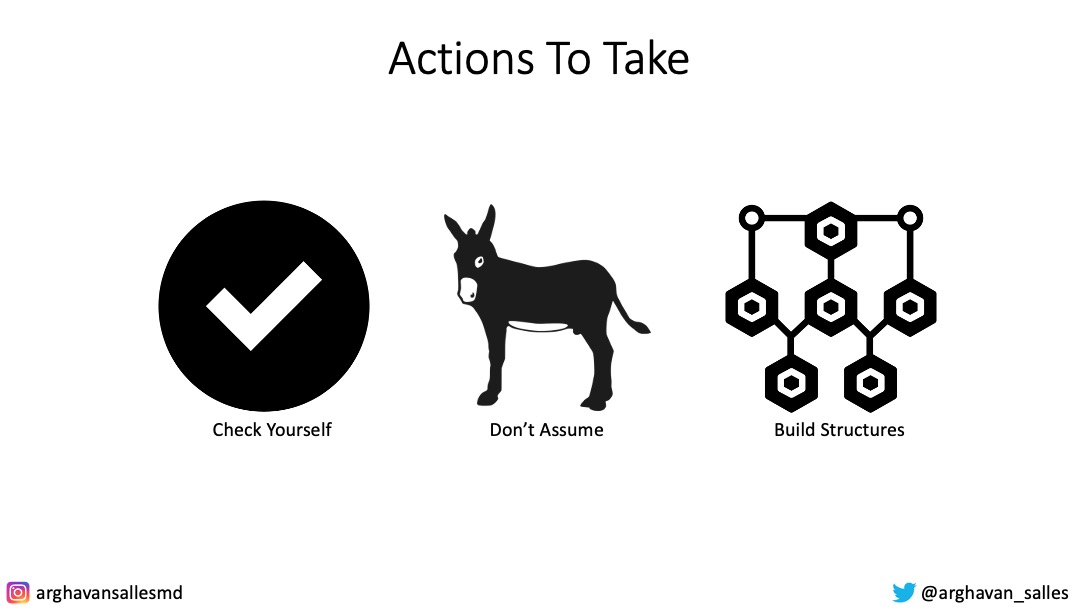

So, what can we do to overcome these biases?

1. We need to check ourselves. When you sit down to eval a trainee or a colleague, are you focusing on the negative things? Are you really doing them justice?

10/

So, what can we do to overcome these biases?

1. We need to check ourselves. When you sit down to eval a trainee or a colleague, are you focusing on the negative things? Are you really doing them justice?

10/

2. Don't assume you know why you are seeing the behavior you are seeing--is there more to the story? Nothing happens in isolation. Work performance depends on many factors aside from intelligence and motivation.

3. Build structures and policy that make it difficult...

11/

3. Build structures and policy that make it difficult...

11/

...to insert your biases. For example, use standardized interview questions and work sample tests as part of hiring.

What can you do to minimize the degree to which your bias affects your evaluation of others? What are you doing that works? I'd love to hear it!

12/12

What can you do to minimize the degree to which your bias affects your evaluation of others? What are you doing that works? I'd love to hear it!

12/12

cc @FutureDocs @NirajGusani @GallodeMoraesMD @DrMarthaGulati @DBelardoMD @AMarshallMD @DrHowardLiu @AmyOxentenkoMD @MVGutierrezMD @AimeeGthePHD @katie_sharkey @susieQP8 @londyloo @pedsmd2b @AmmahStarr @DrAyanaJordan @SAStrongMD

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh