Increasing the maximum sentence for damaging a statue to 10 years is stupid, yes. It reflects distorted priorities, yes.

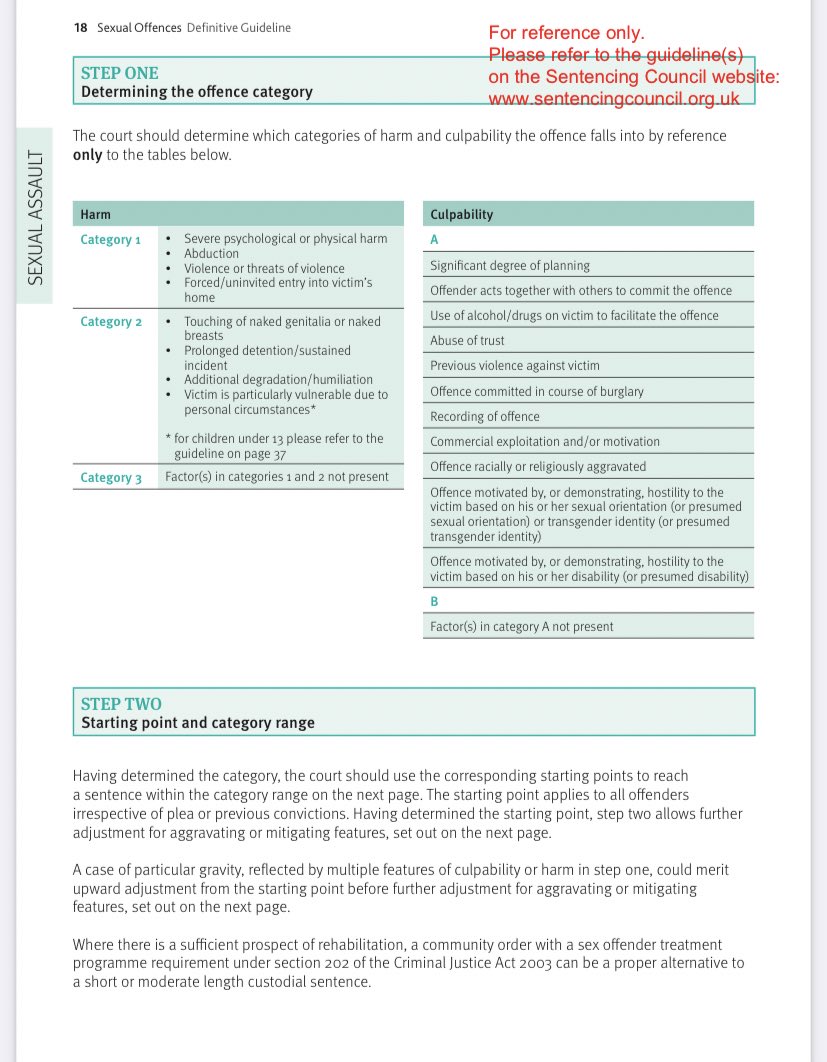

But the maximum sentence for rape is life, not 5 years.

This is a bad point that does nothing for public understanding. #FakeLaw

But the maximum sentence for rape is life, not 5 years.

This is a bad point that does nothing for public understanding. #FakeLaw

https://twitter.com/keir_starmer/status/1371547120080195585

For those struggling (and there are seemingly many), he has cited the maximum theoretical sentence for damaging a statue, and compared it to a figure plucked out of the air, but significantly below the average sentence imposed, for rape.

Intellectually dishonest.

Intellectually dishonest.

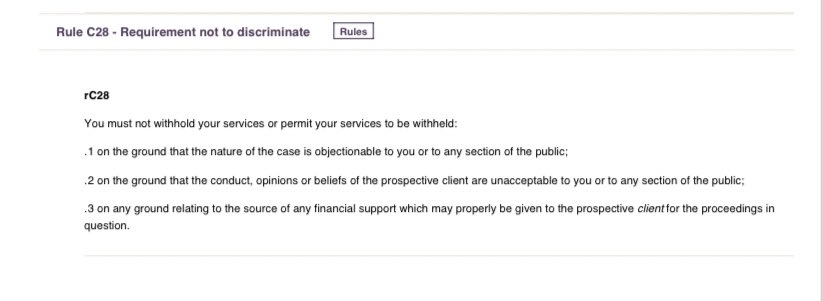

You can make the point that increasing the maximum sentence for low-value damage of statues to 10 years is idiotic, populist guff.

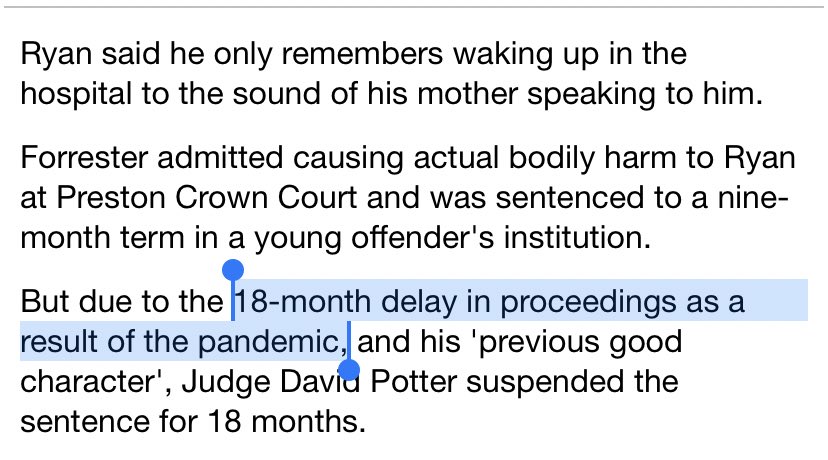

You can make the point that the criminal justice system fails to tackle sexual violence (for many reasons).

But that tweet makes neither point.

You can make the point that the criminal justice system fails to tackle sexual violence (for many reasons).

But that tweet makes neither point.

And it is disheartening beyond measure to see the Opposition descend into a populist arms race on “tough sentencing”, when they know - they *know* - that the problems in criminal justice are so, so much more than that.

https://twitter.com/barristersecret/status/1371030760501747712

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh