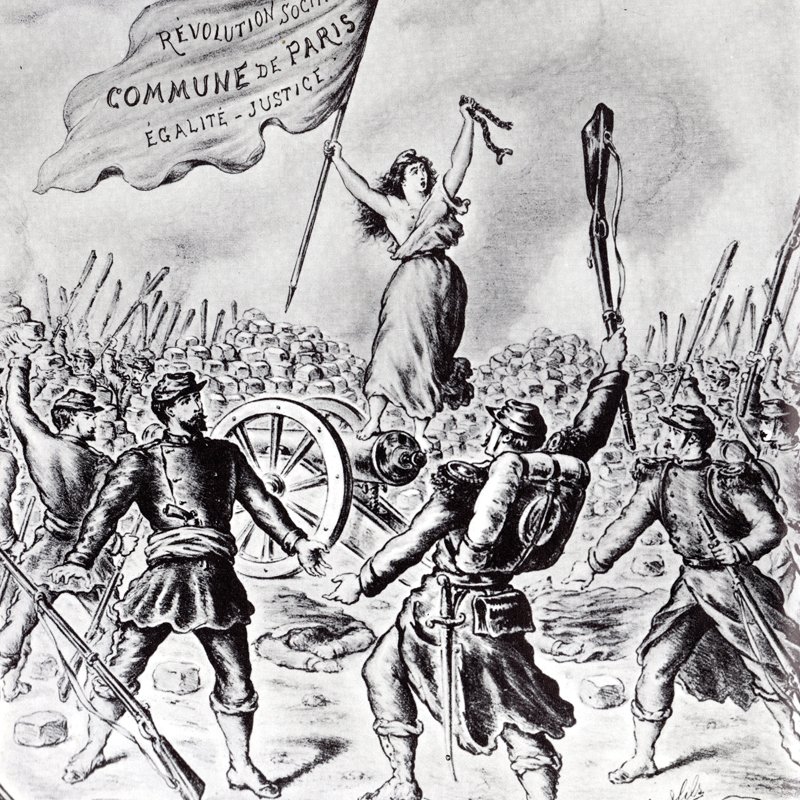

This Day in Labor History: March 18, 1871. The French military attacked the worker movement in Paris with the aim of retaking the city for the nation’s government. Let's talk about the Paris Commune!

This socialist workers movement controlled Paris for two months and was the first revolutionary challenge to European government in the industrial age (which 1789 really was not in France).

It would start the long tradition of revolutionary movements based upon working-class radicalism that would help to define the next century around the world.

The Paris Commune came about as a result of political crisis in France. The Franco-Prussian War of 1870 led to embarrassing losses for the French and Napoleon III. This led to the French abolishing their monarchy and replacing it with the Third Republic.

The workers of Paris, already radicalized and far to the left of the rest of France, feared that the new government would not truly embrace republicanism and instead just be another form of oligarchic rule by the powerful.

They also held the creation of this kind of order contemptible because they had already organized themselves to defend the city against the Germans with little help from the elite. Workers began establishing their own government as a challenge to the new national government.

Urban French workers, especially in Paris, had grown increasingly radicalized over the nineteenth century.

Socialism was much more accepted in the French working class than in the United States and the French workers were working out its tenets at the same time Karl Marx and others was figuring out its theoretical basis.

Of course, the Third Republic was not going to let a bunch of radical workers supersede its power. When the army came into Paris, the national guard refused to hand over their weapons. The government was forced to flee to Versailles.

Obviously this situation was untenable but in the mean time, things got very interesting in Paris. The workers tried to run an alternative government. Louis-Auguste Blanqui, an early communist, headed this government.

It abolished conscription and created a citizens’ army, which also granted the right to bear arms to all citizens. It reestablished the calendar of the French Revolution, building connections with that earlier revolutionary movement. Interest payments on debt were suspended.

It issued a lot of radical statements, especially empowering radical women to play a central role in the struggle. Paule Mink (born Paulina Mekarska) had a long history of radicalism in Paris, including publishing anti-Napoleon III newspapers.

When the commune began, Mink jumped into the fray to demand gender equality, arguing that all workers deserved deliverance from the oppression they faced but that was especially true of women who faced both gender and class oppression.

She set up an ambulance service during the commune and also traveled to other cities around France to try and spur the movement there.

One leading radical woman stated, “The social revolution will not be realized until women are equal to men. Until then, you have only the appearance of revolution.”

But the Paris Commune also struggled to consolidate power and alienated most of the remaining power structure from the old Paris. It also angered most of the rest of France.

Having limited connections with workers outside of Paris and almost none the still largely rural peasantry that made up much of France, this was a urban-based revolution without consent from the majority of the theoretically governed.

The communards also lacked any real way to even spread their message to the provinces, relying on vague hopes of working-class revolt than a meaningful plan.

The Commune was also incredibly fractured ideologically. Some called themselves Jacobins and directly connected themselves to radicals of old. Followers of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon wanted a loose federation of communes.

Blanqui’s communists wanted to use violence to create a revolutionary state. If anything held them together, it was anti-clericalism.

All church property in Paris was confiscated by the revolutionary government. The Commune captured the Archbishop of Paris and executed him on May 24.

The French government was not going to tolerate this radicalism in its capital. Finally, the army marched from Versailles. But retaking the city would be very difficult. On April 2, troops started the attack but the communards held out for several weeks.

The revolutionaries had built 600 barricades around the city that had to be cleaned out one by one. The French army entered Paris on May 21 and crushed the movement by May 28. The small commune movements in other French cities were also decimated by this time.

Along the way, much of Paris burned, some claim by the radical feminists of the Commune although it seems more likely that most of the fires originated from the general chaos of a civil war.

The French army claimed about 887 dead; estimates of Parisian citizens killed usually revolve around 20,000, although some recent totals suggest more like 10,000.

At the Père Lachaise Cemetery, the army lined up and executed 147 Commune members. About 6000 communards fled as the fighting doomed their experiment, fleeing to surrounding nations.

In the United States, the Paris Commune itself did not have a major impact on American workers, but scared the capitalists, police, politicians, and journalists of the nation as it entered the Gilded Age.

During the next decade, any workers’ movement in the U.S. was darkly compared to the Paris Commune as the future if these workers continued to organize

For example, the response to the unemployed organizing in New York’s Tompkins Square Park was completely disproportional with the threat these workers posed.

Only wanting to march to the meet with the mayor, they were beaten by the cops while journalists screamed about the Paris Commune coming to the United States.

To put this into perspective, the head of this movement was Peter McGuire, founder of the United Brotherhood of Carpenters, even at its founding one of the most conservative unions in the United States.

In Europe, the story of the Paris Commune was one of possibility, not failure, as it provided evidence that workers could act collectively to build an alternative society, as well as the use of political violence to defend that society against counterrevolutionary forces.

Back Saturday with a brand new thread on the successful organizing of Homestead Steel in 1882.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh