For how many generations will reservations continue, the SC asks. The question arises because quotas are seen as a concession given to disadvantaged castes.

What about those who benefited from discrimination? How did they become casteless & meritorious?

A history in 8 tweets👇

What about those who benefited from discrimination? How did they become casteless & meritorious?

A history in 8 tweets👇

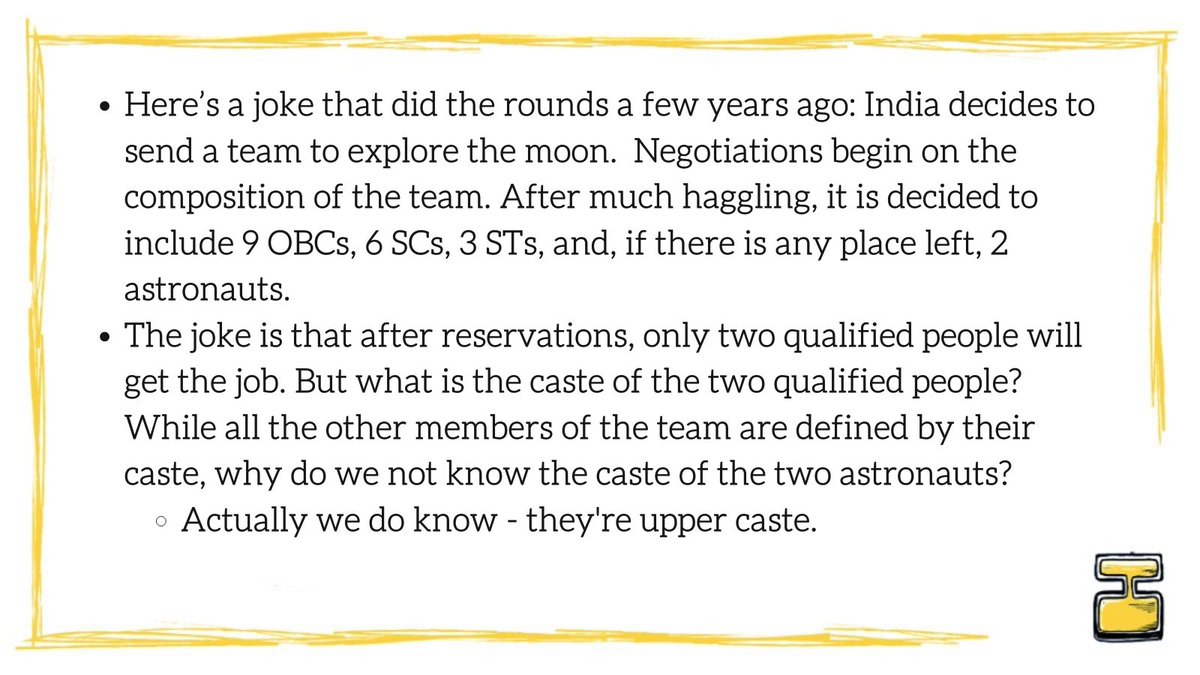

1. There is a strange paradox in India today. Upper castes constantly insist that they don’t see caste or benefit from it. For them, caste identity is no longer associated with hierarchy and discrimination, but with modern concepts such as merit and development instead.

2. But for lower castes, their lives seem to be defined entirely by caste — even their best achievements are always tainted with the stigma of reservations.

3. This state of affairs goes back to the days of the freedom struggle. By the early 1900s, Congress leaders, who were leading the nationalist movement, knew they had to do something about caste – either reform it or abolish it. But they didn’t agree on what those words meant.

4. As British rule over the subcontinent approached its end, the Congress needed to solidify its claim of representing “India.” To achieve this, it blocked the Dalit demand to be treated as a separate group, thus enlarging its votebase and masking its upper caste identity.

5. After independence, India’s new constitution abolished discrimination based on caste. Even though it allowed “compensatory discrimination” in the form of reservations in order to remedy the damage of the caste system, it framed this as an “exception” to the rule.

6. This meant that caste was now – legally speaking – only a source of disadvantages. Upper castes could see themselves as “caste-less” – all the advantages they had derived from caste could now be represented as the result of hard work and “merit.”

7. It was only in the 1980s, when the Mandal Commission proposed reservations for OBCs, that there was broad public debate about how the unreserved or general category had become a space reserved for upper castes who were less than 20% of the population.

8. Today, it seems that younger generations of upper caste families might actually genuinely believe their own claims of being “casteless”. Since their parents transformed their caste capital into wealth and social capital, they don’t see the role of caste in their lives.

Source text: Towards a Biography of the ‘General Category’

Author: Satish Deshpande

For more details on each point and links to the original article, please visit our website...

indiaink.org/2021/03/22/cas…

Author: Satish Deshpande

For more details on each point and links to the original article, please visit our website...

indiaink.org/2021/03/22/cas…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh