Mezzanine financing is one of the most opportunistic ways to allocate capital, whether it's in public or illiquid markets — and yet it is very misunderstood.

In this super thread, which will be ongoing, I will disclose the theory & practice I've learned about the asset.

In this super thread, which will be ongoing, I will disclose the theory & practice I've learned about the asset.

Mezzanine financing occurs in situations where a business or a project has insufficient creditworthiness or collateral to borrow in classic (& cheaper) form like a bank loan or senior debt & potentially where owners/sponsors refuse to dilute shareholders or give up legal control.

From what I've learned over the years, mezzanine deals are looked at differently in the US vs other developed markets like Eurozone & Anglo-Saxon jurisdictions.

There is a large misunderstanding between players, both with private equity & real estate, due to these developments.

There is a large misunderstanding between players, both with private equity & real estate, due to these developments.

Some of these differences fall to how mature the broad lending is, while others due to the tax code which has traditionally changed the way investors look at & allocate to opportunities.

From the real estate perspective, something I'm more familiar with, the US is the only...

From the real estate perspective, something I'm more familiar with, the US is the only...

...major economy that subsidies RE loans via Gov agencies. Senior lending occurs more easily and the need for mezzanine finance isn't as high.

Moreover, the US tax code enables deferral in RE (1031 exchange) so investors are far more likely to engage in equity rather than debt.

Moreover, the US tax code enables deferral in RE (1031 exchange) so investors are far more likely to engage in equity rather than debt.

With that in mind, mezzanine finance has developed more in the private equity space when it comes to mergers & aqusiations, or even expansions / venture capital space.

On the other hand, in UK & AU and some parts of EU the situation is different for all the obvious reasons.

On the other hand, in UK & AU and some parts of EU the situation is different for all the obvious reasons.

Oaktree Capital real estate memo writes:

"Outside the US, real estate finance is primarily a bank-led market.

We see greater opportunities for non-bank lenders as banks retrench and the maturity wall mounts."

"Outside the US, real estate finance is primarily a bank-led market.

We see greater opportunities for non-bank lenders as banks retrench and the maturity wall mounts."

A large RE debt fund shared mindblowing statistic:

"Australia's major banks share of the commercial real estate debt had reduced from 85% to 71%. The expectation is it will fall further to 65% in coming years."

Private capital is filling the funding gap via mezz products.

"Australia's major banks share of the commercial real estate debt had reduced from 85% to 71%. The expectation is it will fall further to 65% in coming years."

Private capital is filling the funding gap via mezz products.

Before we discuss different types of mezzanine products (they range from debt-like to equity-like bets),

I want to share a story of Warren Buffett — who is one of the most famous and extremely opportunistic mezz investors out there.

The bet he made in Sept 2008 is legendary!

I want to share a story of Warren Buffett — who is one of the most famous and extremely opportunistic mezz investors out there.

The bet he made in Sept 2008 is legendary!

Global banks together with many other financial firms were facing completely frozen capital markets and lending lines.

Even for the mighty Goldman Sachs, the ability to tap new funding lines via markets was shut off.

The crisis was now in full swing & Mr Buffett knew it.

Even for the mighty Goldman Sachs, the ability to tap new funding lines via markets was shut off.

The crisis was now in full swing & Mr Buffett knew it.

It was during this time, as the majority of market participants became desperate for capital, that Buffett & Berkshire made a $5 billion investment — neither a classic senior loan nor a common equity position.

A canny mezzanine deal negotiated partly as debt & partly as equity.

A canny mezzanine deal negotiated partly as debt & partly as equity.

Warren entered into a deal with GS by negotiating a 10% fixed dividend on preferred shares, which will go on to yield $500 million annually.

On top of that, he also negotiated an additional warrant attached to the pref shares with GS having an option to call in for redemption.

On top of that, he also negotiated an additional warrant attached to the pref shares with GS having an option to call in for redemption.

The bank did so in 2011, but a premium of 10% had to be paid over par value, plus accrued dividends (dividends for pref share must always be paid, or go into arrears).

In the end, Warren took home a massive return over the 3 year period, without buying more risky common stock.

In the end, Warren took home a massive return over the 3 year period, without buying more risky common stock.

While we aren't Warren Buffett and we won't be negotiating billion-dollar deals with Goldman's of this world,

All of these mezzanine family of products and the ability to negotiate deals are available to private investors like us in smaller PE, VC & RE opportunities worldwide.

All of these mezzanine family of products and the ability to negotiate deals are available to private investors like us in smaller PE, VC & RE opportunities worldwide.

From a balance sheet perspective, a mezzanine group of products is positioned in between senior debt & common equity.

The risk is therefore subordinated to traditional bank loans but safer to common equity.

So is the return, which is higher than debt but lower than equity.

The risk is therefore subordinated to traditional bank loans but safer to common equity.

So is the return, which is higher than debt but lower than equity.

Mezzanine investors are bipolar in many ways.

On one side, they are often concerned about protecting capital.

Due to its senior nature to comm equity, mezzanine investments have a "margin of safety" or protection buffer over common equity (this is credit investors' hat).

On one side, they are often concerned about protecting capital.

Due to its senior nature to comm equity, mezzanine investments have a "margin of safety" or protection buffer over common equity (this is credit investors' hat).

On the other side, they are often very good negotiators — this is probably one of the more important aspects of investing in mezzanine debt.

Therefore, they also attempt to structure opportunities so giving them participation in the upside (this is the equity investors' hat).

Therefore, they also attempt to structure opportunities so giving them participation in the upside (this is the equity investors' hat).

Plenty of real-world examples and case scenarios coming later on in the thread, including:

• deals we have done in different countries

• good deals we negotiated into great deals

• deals we didn't invest in & reasons why

• deals we have done in different countries

• good deals we negotiated into great deals

• deals we didn't invest in & reasons why

https://twitter.com/EvanSBernstein/status/1377058766278000643?s=20

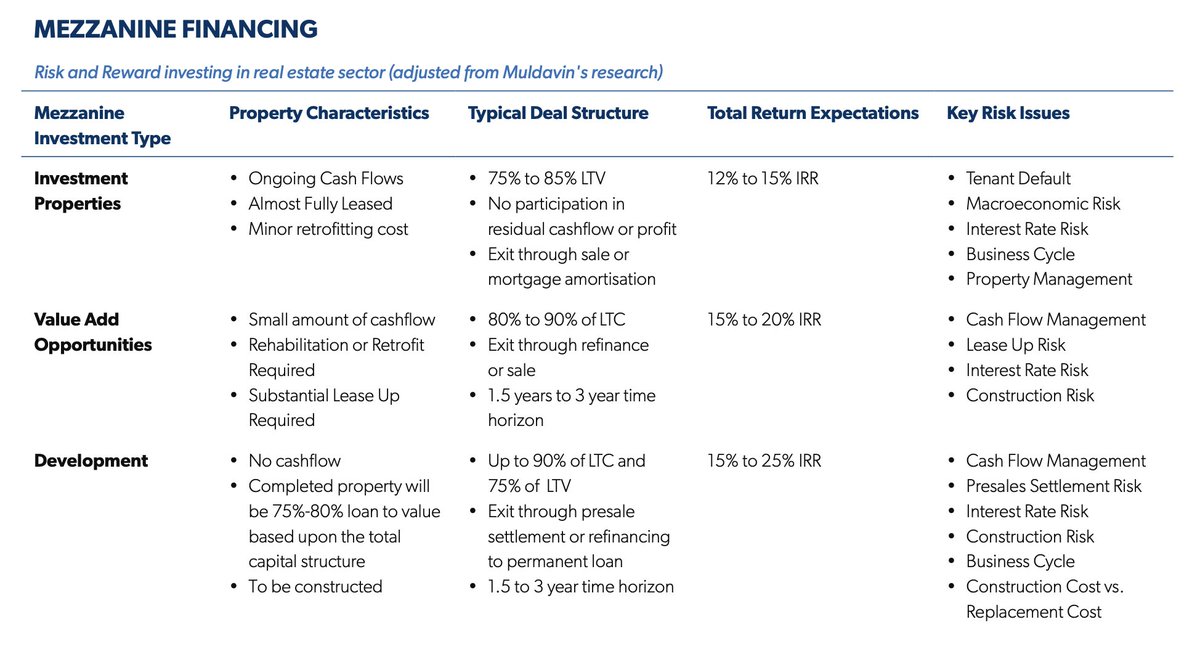

While mezzanine financing is used in recapitalization, LBOs, M&A, etc — we are most familiar with bridging & development finance in real estate.

Typical RE mezzanine deals are:

• (partly) stabilized properties

• value add / rehab projects

• developments / repositioning

Typical RE mezzanine deals are:

• (partly) stabilized properties

• value add / rehab projects

• developments / repositioning

Most investors will look at the table in the previous tweet & assume one of two things:

1) are such high rates of return possible, while the stock market has averaged only 8-10% over the last 20, 50 & 100 years?

Answer: illiquid assets (alternatives) have a return premium.

1) are such high rates of return possible, while the stock market has averaged only 8-10% over the last 20, 50 & 100 years?

Answer: illiquid assets (alternatives) have a return premium.

2) are such high rates of return possible, considering return compression today & the future expected returns falling even further?

Answer: broadly speaking, yes but several countries (i.e. UK) have experienced a credit crunch due to #Brexit & offer amazing opportunities.

Answer: broadly speaking, yes but several countries (i.e. UK) have experienced a credit crunch due to #Brexit & offer amazing opportunities.

Since mezzanine risk theoretically sits inbetween senior debt & common equity, so should the reward.

However, success comes from achieving superior risk-adjusted returns.

This is accomplished by either finding high mezzanine returns for senior-like risk, or better yet...

However, success comes from achieving superior risk-adjusted returns.

This is accomplished by either finding high mezzanine returns for senior-like risk, or better yet...

...very high equity-like returns for 2nd lien-like risk. One is compensated a high return for a lower risk being taken.

Additionally, while performing due diligence, mezzanine investors shouldn't only think like bankers or lenders, but instead also like equity investors.

Additionally, while performing due diligence, mezzanine investors shouldn't only think like bankers or lenders, but instead also like equity investors.

Can such superior risk-adjusted returns be easily accomplished?

Definitely not. Fantastic deals are often found with motivated counterparties & in distressed situations.

It is all very similar in any asset class & any investment strategy. Finding needles in the haystack.

Definitely not. Fantastic deals are often found with motivated counterparties & in distressed situations.

It is all very similar in any asset class & any investment strategy. Finding needles in the haystack.

Let us get back to the real estate side of mezzanine financing.

There are numerous ways to participate in an opportunity & the execution is only limited by your imagination + negotiation skills.

(I will probably repeat many more times that mezzanine finance = negotiations)

There are numerous ways to participate in an opportunity & the execution is only limited by your imagination + negotiation skills.

(I will probably repeat many more times that mezzanine finance = negotiations)

Why do we prefer mezzanine finance applied in real estate, over companies and other opportunities?

Ultimately it comes down to collateral. Putting your creditor hat on, we know (all else being equal) that real estate collateral is stronger than personal or corporate collateral.

Ultimately it comes down to collateral. Putting your creditor hat on, we know (all else being equal) that real estate collateral is stronger than personal or corporate collateral.

In the RE mezzanine group, there are equity deals structured as debt for various reasons (better protection in case of bankruptcy).

Also, there are actual loans structured as equity, also for various reasons (e.g. taking advantage of the US 1031 exchange).

Get creative.

Also, there are actual loans structured as equity, also for various reasons (e.g. taking advantage of the US 1031 exchange).

Get creative.

Furthermore, sometimes senior lenders will not allow mezzanine, so instead of being creative, you’ll have to be a problem solver.

Typically, the mezzanine lender will change his outfit by becoming a preferred equity investor.

This still gives the lender a preferred return…

Typically, the mezzanine lender will change his outfit by becoming a preferred equity investor.

This still gives the lender a preferred return…

…plus priority in the unlikely event deal would enter administration (a process where a third party trustee liquidates assets) & finally a priority of exit in the event of a sale, refinance, or any other form of exit.

Obviously, pref equity isn’t as sound as a 2nd lien…

Obviously, pref equity isn’t as sound as a 2nd lien…

…therefore an investor will have an upper hand during negotiations with the sponsor.

It is critical to explain how the situation has changed whereby the lender is now taking on far more equity-like entrepreneurial risk.

Hence, the compensation should match that risk.

It is critical to explain how the situation has changed whereby the lender is now taking on far more equity-like entrepreneurial risk.

Hence, the compensation should match that risk.

The common theme of mezzanine debt investing is for potential returns to be close to those offered by private equity & superior to public equity — but with reduced risk.

While this isn't going to be broadly available all the time, correct deal selection will accomplish the goal.

While this isn't going to be broadly available all the time, correct deal selection will accomplish the goal.

The key to achieving superior returns with lower risk:

• relationships in the industry to access attractive deal flow

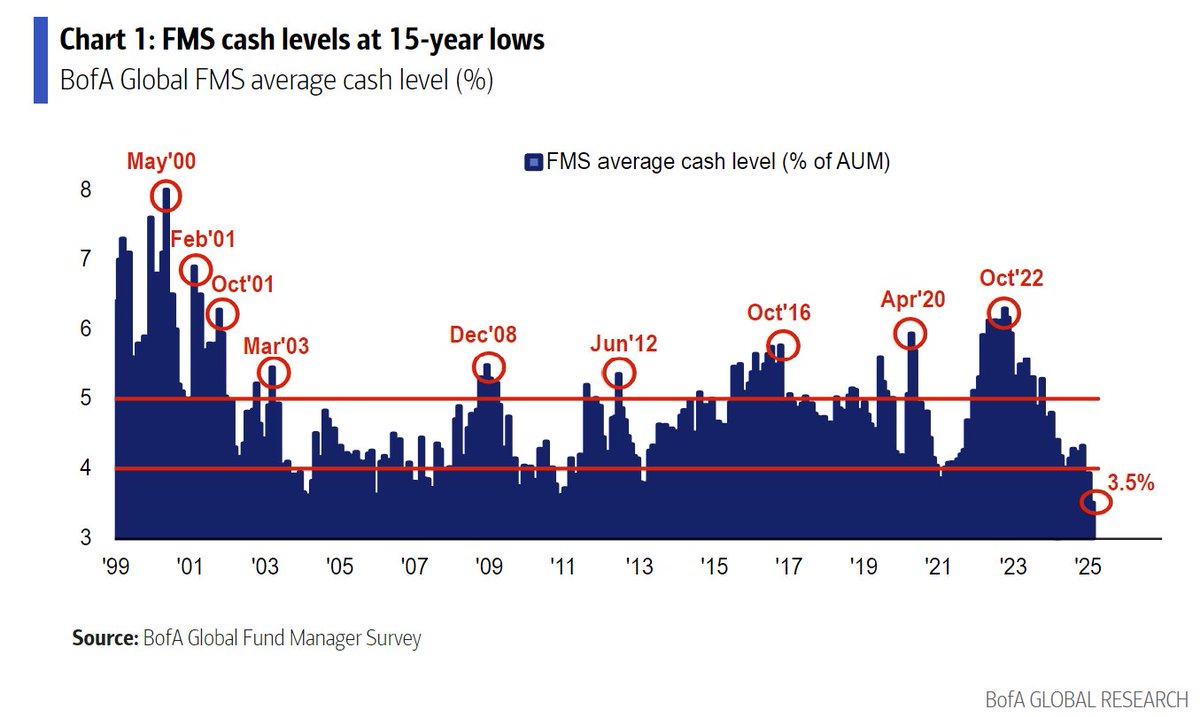

• timing the cycle as distress has funding gaps & need for capital

• negotiate to captures upside from equity participation while receiving mezz interest

• relationships in the industry to access attractive deal flow

• timing the cycle as distress has funding gaps & need for capital

• negotiate to captures upside from equity participation while receiving mezz interest

Mezzanine finance as an investment proposition takes form in many different ways & styles.

Either short-term funding needs or long-term loans in asset sectors like private equity, infrastructure, project financing & real estate.

It is all about negotiated bespoke solutions.

Either short-term funding needs or long-term loans in asset sectors like private equity, infrastructure, project financing & real estate.

It is all about negotiated bespoke solutions.

Since (almost) everything is negotiable, mezzanine investors should consider the following playbook to reduce the risk of default:

• superior access to full information (macro & micro) regarding a particular opportunity to make the best possible decision/judgment

• superior access to full information (macro & micro) regarding a particular opportunity to make the best possible decision/judgment

• deal selection should start with a banker's hat, meaning thinking more like a lender instead of like an equity investor

• deal selection should also focus on credit quality & creditworthy borrowers with strong balance sheets + reliable recourse (personal guarantees)

• deal selection should also focus on credit quality & creditworthy borrowers with strong balance sheets + reliable recourse (personal guarantees)

• well negotiated terms & conditions add downside protection structure while maintaining very high levels of return (something common equity cannot achieve)

• negotiate a seat at the table with voting rights, in the unlikely event project goes into administration (default)

• negotiate a seat at the table with voting rights, in the unlikely event project goes into administration (default)

KKR's London-based mezzanine finance office on the advantages of this strategy...

The reasons mezzanine is favored over high yield:

• certainty of execution

• flexibility on the design of terms

• sponsor/dealer relationship through the life of the transaction

The reasons mezzanine is favored over high yield:

• certainty of execution

• flexibility on the design of terms

• sponsor/dealer relationship through the life of the transaction

While the risks with mezzanine investing are lower than that of equity, they aren't to be taken lightly.

Various research over the years shows, on average 10-15% of mezz loans can default.

Positive caveat?

Research also shows, on average, 40-50% of the money is recovered.

Various research over the years shows, on average 10-15% of mezz loans can default.

Positive caveat?

Research also shows, on average, 40-50% of the money is recovered.

If you've gotten anything from the thread so far, it should be to focus your attention on the cycle risks (early-cycle vs late-cycle valuation risks); strong credit quality & borrower creditworthiness; well-negotiated terms for downside protection & several other key factors.

Also do not underestimate investor behavior in different regions of the world, and their aggressive vs conservative underwriting styles.

Centre of Private Equity Research covered over 4,200 mezzanine transactions from 1982 until 2008 (prior to the Global Financial Crisis).

👇

Centre of Private Equity Research covered over 4,200 mezzanine transactions from 1982 until 2008 (prior to the Global Financial Crisis).

👇

• In the US, 70% of mezz are for buy-outs & 30% for growth strategies. In Europe 88% for buy-outs.

• Interestingly, Euro mezz deals tend to have lower defaults & higher recoveries than the US

• Total loss rates, after default & recoveries, are 2.8% in EU & 8.1% in the US

• Interestingly, Euro mezz deals tend to have lower defaults & higher recoveries than the US

• Total loss rates, after default & recoveries, are 2.8% in EU & 8.1% in the US

Those two stats should stand out.

In summary, while 10-15% of the mezz deals could default (to be higher in the next downturn), after recoveries the default rate is far smaller.

Therefore, our goal has always great deal selection to achieve equity-like returns for debt risk.

In summary, while 10-15% of the mezz deals could default (to be higher in the next downturn), after recoveries the default rate is far smaller.

Therefore, our goal has always great deal selection to achieve equity-like returns for debt risk.

Howard Marks & Raj Makam of Oaktree discuss risk management between mezzanine vs equity investments.

While brief, the video gives a perfect example of how private investors can actively choose their risk tolerance & execute their preferred mandate.

👇

While brief, the video gives a perfect example of how private investors can actively choose their risk tolerance & execute their preferred mandate.

👇

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh