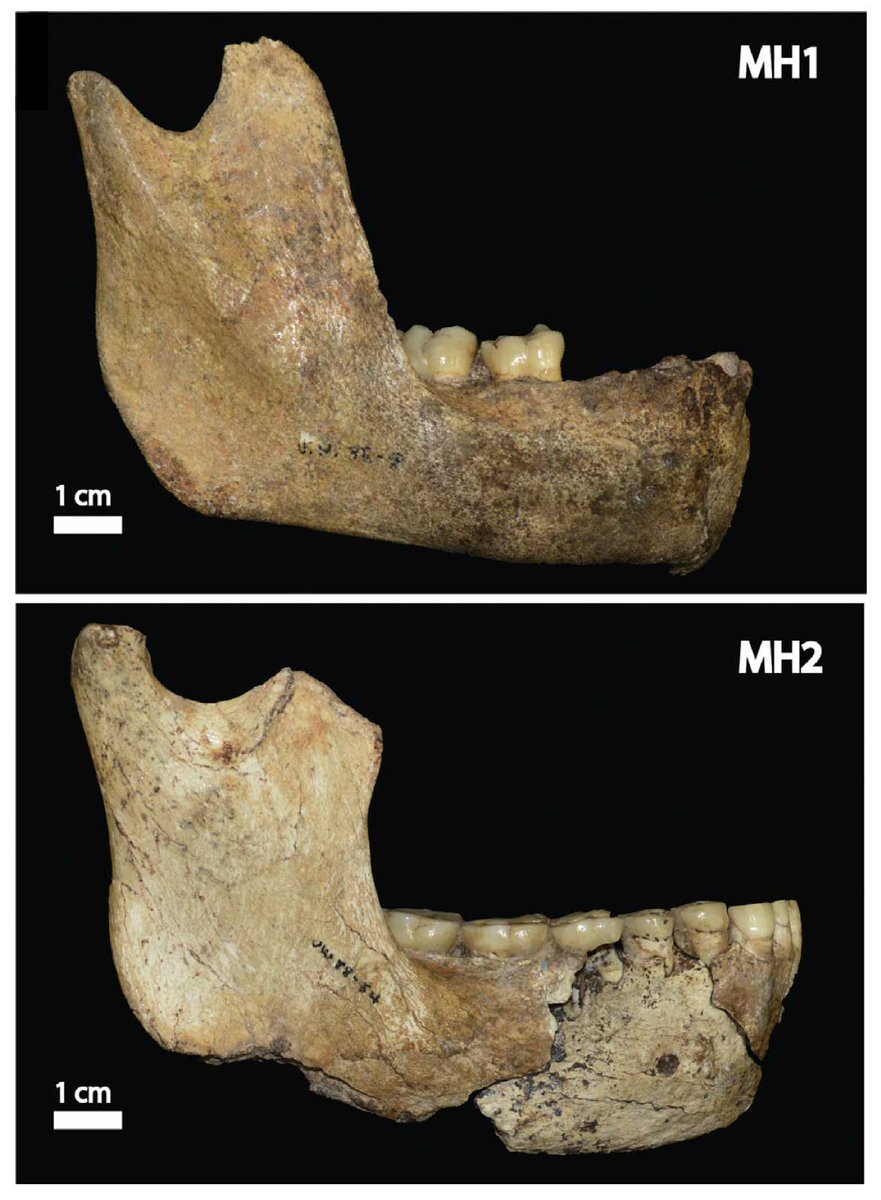

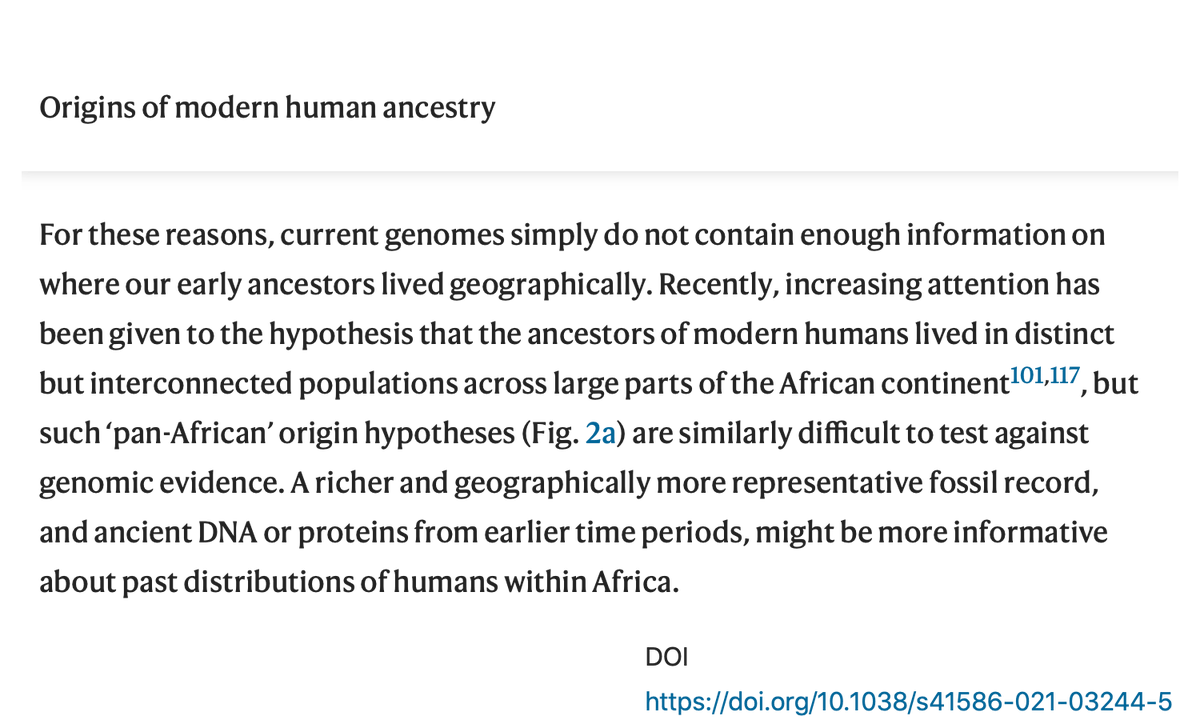

A hint of the social behavior of early Homo erectus comes from the earliest known #hominin to survive with near total loss of teeth, 1.8 million years ago. Some wild primates also survive years with little functional dentition. #paleoanthropology #FossilFriday

For years, anthropologists have looked at the survival of older people with tooth loss as a possible indication of social caring, empathy, and value of tradition and knowledge to social groups—once with Neandertals, more recently with H. erectus. #paleoanthropology

Some have criticized inferences about social care in these human relatives, by pointing out other primates that sometimes survive. This wild chimpanzee skull in the collection of the @goCMNH is a great example, with loss of all but one molar and premolars.

But all this does is show that sociality is important to survival with disability outside of hominins. Our lineage is not uniquely social—many elements of hominin social life are shared more broadly across social mammals including primates.

We do learn about humanity by working to understand the lives of exceptional individuals in the past. Sometimes the humanity we learn about is that part we share with other species.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh