Lactase persistence and dairying on the surface seem to be a simple and compelling example of gene-culture coevolution in humans. And yet there are patterns that confound the simplistic story. I appreciate that @Maddy_Bleasdale et al discuss some of those. nature.com/articles/s4146…

Several aspects of lactase persistence genetics are not being covered well by press accounts of this paper. Journalists have gone with a pretty simple "counterintuitive lede", i.e., people were drinking milk before lactase persistence mutations were common.

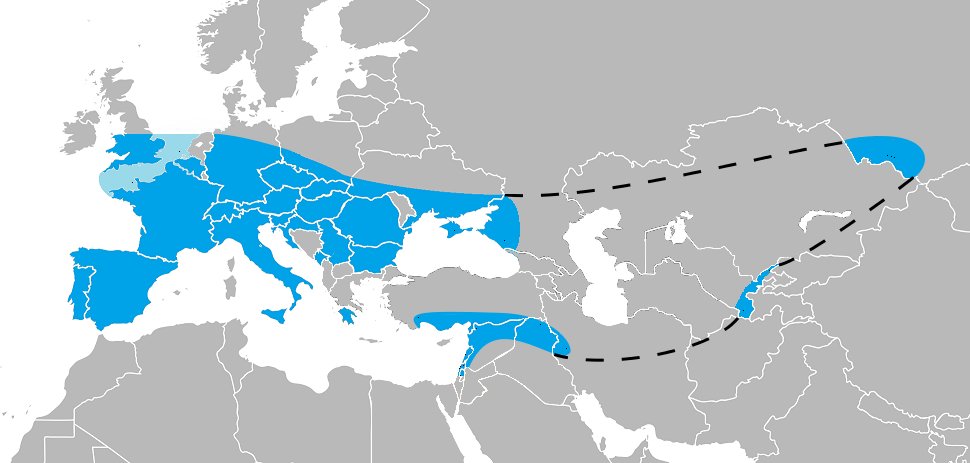

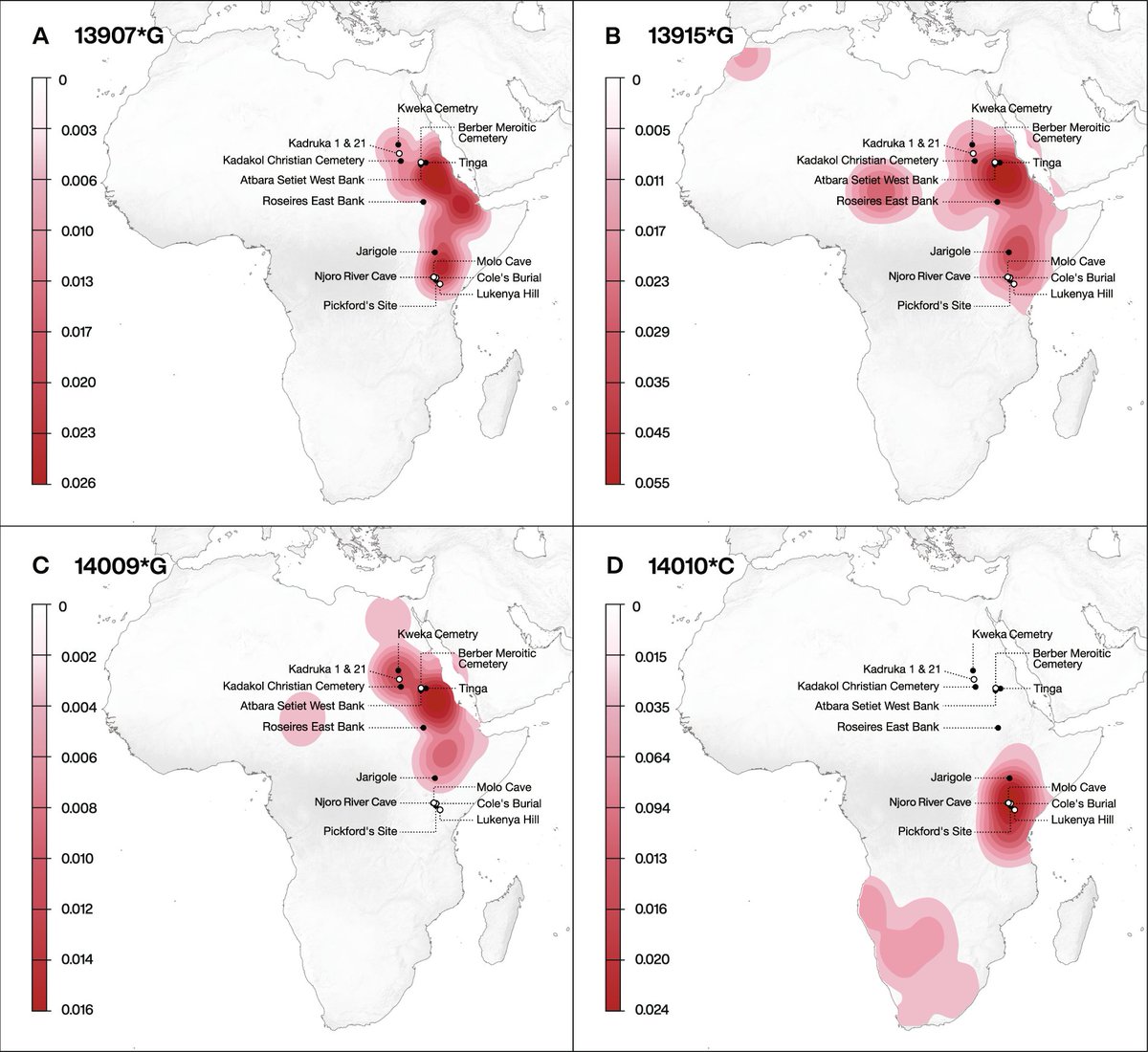

A look at the great frequency maps in the paper is enough to remind folks of the reality that most lactase persistence-associated alleles *still* aren't very common. They have frequency maxima of 2-5% today and are highly localized.

A complication is that when different mutations with similar effects exist within a local population, selection eventually becomes less effective on any one of them alone. Lots of overlap in these distributions (and we can include the 13910 C>T variant introduced from Eurasia).

It's tough to assess presence/absence of low frequency variants with aDNA, which has small sample size. As the paper points out, so far with n~100, only one archaeological individual had one of the alleles. But the skeletal sample doesn't match up well with the current hotspots.

Understanding the joint dynamics of the five alleles would be amazing, and the lack of them in archaeological samples makes it seem this might be in reach with sequencing of large samples in the areas where the mutations are common today.

But to be honest, while it's a great evolution question, we should be focusing on aspects of it that make a difference to future research participants. The archaeology and calculus work is valuable because it builds connections across cultural and genealogical histories.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh