As I mentioned, I've been looking at #EricKaufmann's report on #AcademicFreedom. I want to share another head-scratching moment with you today. 1/

My earlier thread:

My earlier thread:

https://twitter.com/Katja_Thieme/status/1379139835894489088?s=20

Top of the report is a set of questions for which he received answers from 803 US scholars in social sciences & humanities. Here are questions 1-3 along with the graph representing the answers. In the report, the answer key is: 1. support, 2. oppose, 3. neither, 4. don't know. 2/

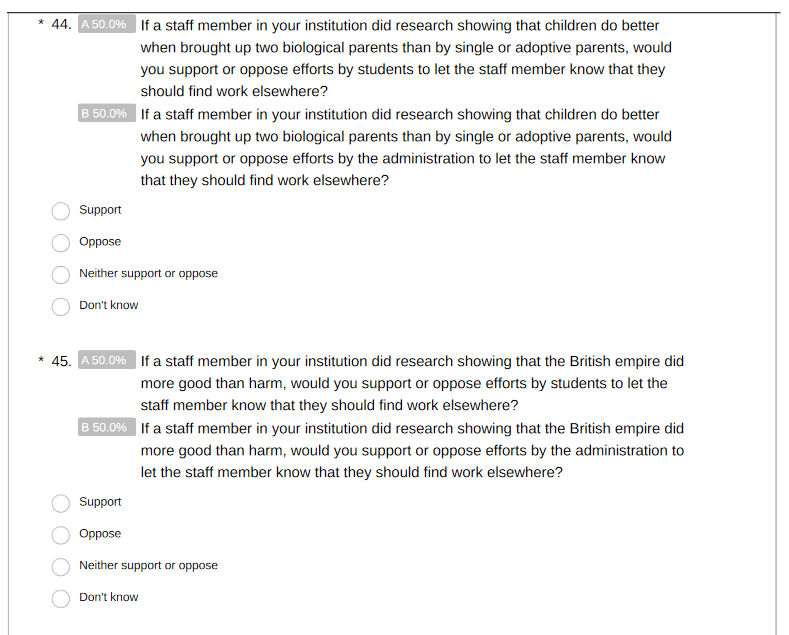

Participants were given 1 of 2 versions of each question with either students or admin campaigning. There is a difference between the two. We might question answers being lumped together into "students/the administration" as well as the very odd "find work elsewhere" phrasing. 3/

But okay. You see that in each of these questions--questions with nice parallel structures for both scenario and answer options--the number of respondents who support the campaign to "let the staff member know that they should find work elsewhere" is at 7-8%. 4/

Now comes what's question 4 in the report and in the above graph. Prepare yourself for a very convoluted scenario. 5/

My immediate thought is: Why are the answers presenting what should be scenario content, and why are there different answer options than in the previous 3 questions? The answer options here don't map at all onto a scheme of 1. support, 2. oppose, 3. neither, 4. don't know. 6/

But look how neatly #EricKaufmann managed to fit these convoluted answers that do not match the answer scheme of questions 1-3 into the same graph with questions 1-3. 7/

And lo, now we have 18% of respondents who "support" a campaign to "oust a dissenting academic." This then becomes the basis of #EricKaufmann's claim that 7-18% of US faculty "would support dismissal campaigns that directly violate academic freedom." 8/

We can add that the latter scenario has strong echos with highly publicized recent cases, e.g., James Damore and Alessandro Strumia, and that people in social sciences and humanities fields are likely aware of both these real-life cases and the research in question. 9/

The termination of Damore's employment was upheld by by a labour board and Strumia's talk was a personal diatribe far far outside his area of expertise which didn't stand up to any research standards. 10/

https://twitter.com/Katja_Thieme/status/1047132615847727108?s=20

When Strumia was kicked out at CERN that was a fellowship position from which he was fired. He retained his professorship at the University of Pisa. His academic freedom as a faculty member was not threatened. 11/

My point is: when reading Kaufmann's scenario, participants can think of several real-life cases, famous or not, where a petition to fire someone can apply to different types of positions. Only some of these will amount to a threat to academic freedom. 12/

Visiting fellowships (as in Strumia's CERN case and #JordanPeterson's at Cambridge) and administrative posts (like Stephen Hsu's vice presidentship) are different from an employment contract as a permanent or contingent faculty member.

The details matter. 13/

The details matter. 13/

Some excellent points on how administrative positions come with limits to one's #AcademicFreedom in this piece by Shannon Dea. 14/

https://twitter.com/Katja_Thieme/status/1381364869610401793?s=20

There's value in asking, as Kaufmann does, people's opinions about these hypothetical scenarios--which might be less hypothetical in respondents' minds--and taking a measure of how many people are in favour of options that are more or less threatening to academic freedom. 15/

If you really want to talk about the state of academic freedom, however, you have to look at actual cases and sort out their details. Kaufmann doesn't do any of that. 16/

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh