1/ The @nytimes has a good interactive story on the safety of flying during the pandemic, but they didn’t discuss boarding & deboarding. Judging by CO2 readings I saw on recent flights, this is the most dangerous part of flying. #covidco2 #COVIDisairborne

nytimes.com/interactive/20…

nytimes.com/interactive/20…

2/ By now there is overwhelming evidence #COVIDisAirborne. It’s transmitted mainly by shared air, i.e. inhaling the air others have exhaled, which contain aerosols—tiny, liquid particles that float suspended in air for seconds to hours, depending on size.

https://twitter.com/kprather88/status/1301531865283616768

3/ There’s no easy way to measure virus levels in the air, but CO2 is a good proxy measure of risk. Outdoor CO2 levels are ~410 ppm, but since we exhale CO2, indoor concentrations are higher. The higher the CO2 level, the more air you’re sharing.

https://twitter.com/jljcolorado/status/1379940559763214339

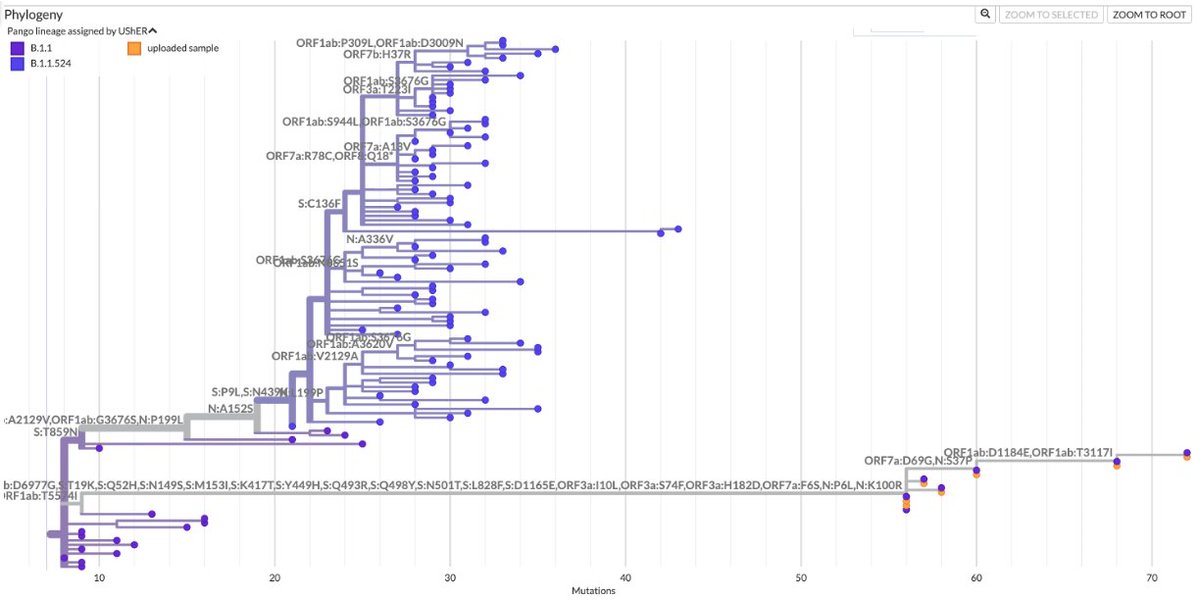

4/ I used an Aranet CO2 meter, which was tested & recommended by @jljcolorado, a top aerosol expert. I flew from Ft. Wayne, IN (FWA), to Rochester, MN (RST) with a layover at Chicago. FWA was not busy, & the CO2 ranged from 516 to 546 ppm.

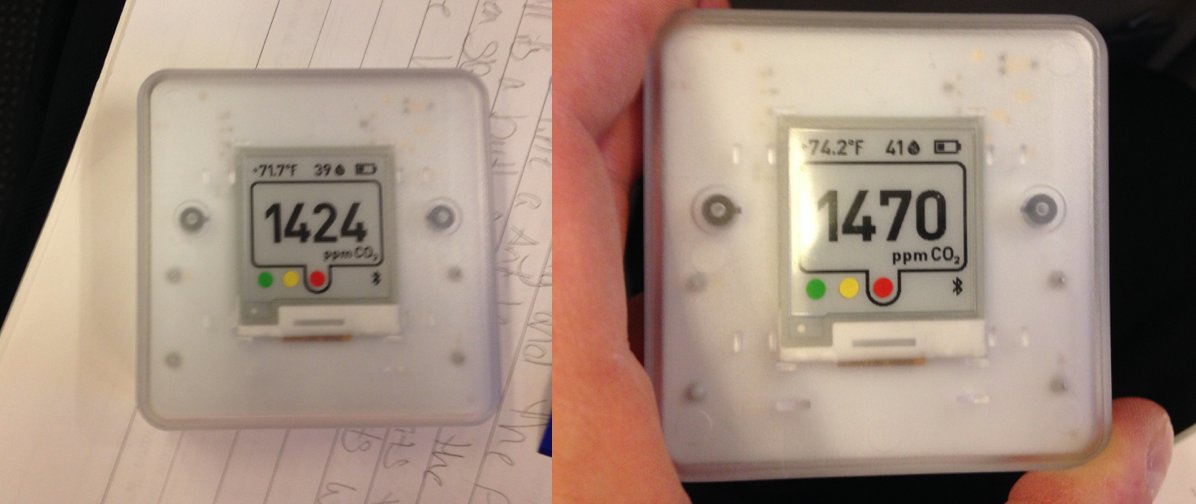

5/ When we first sat down on the plane, the CO2 level was at 1424. Four minutes later, it was 1470. Over the course of the next 6 minutes, the CO2 concentration rose steadily.

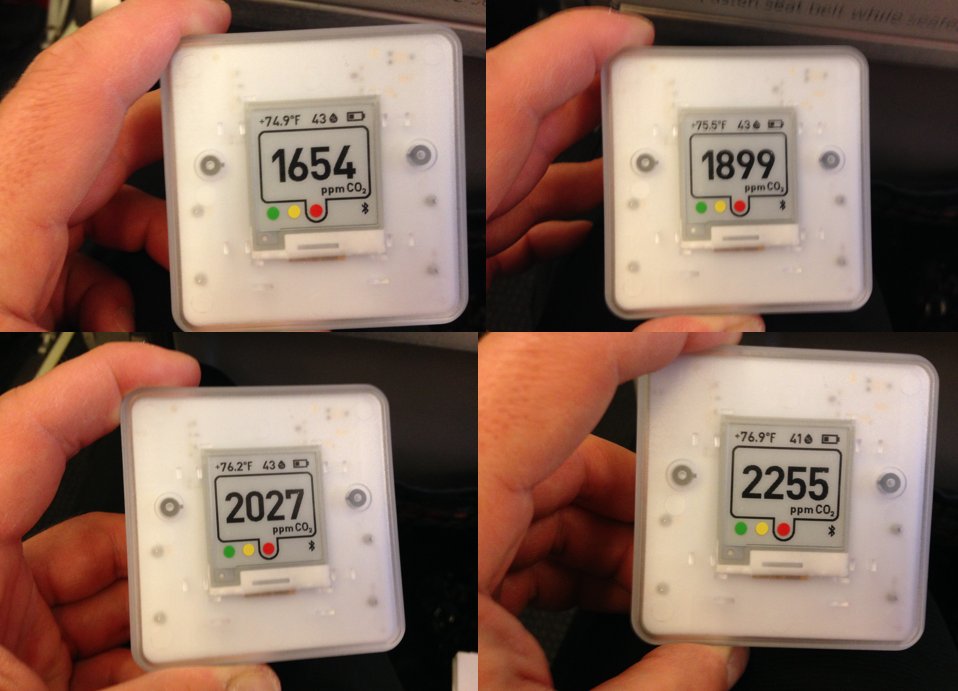

6/ In the next four minutes, the CO2 level rose from 1654 ppm to 1899 to 2027 to 2255. Most IAQ experts, including @linseymarr, recommend keeping CO2 below 700 for a multitude of reasons.

https://twitter.com/linseymarr/status/1374069662930112519

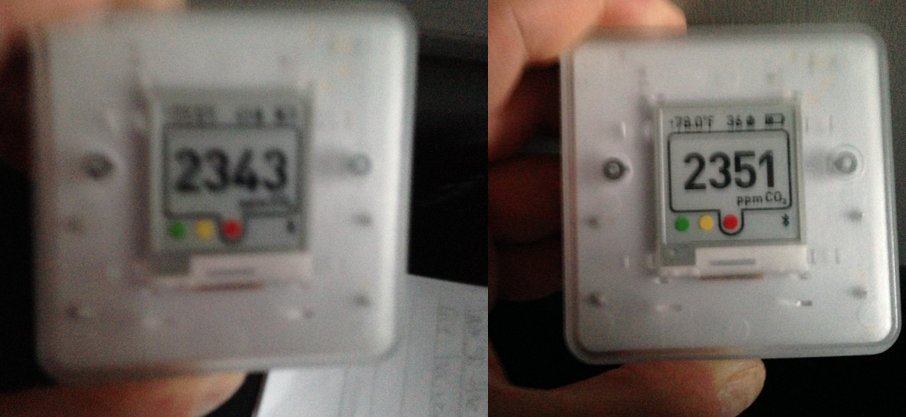

7/ The next two pictures are quite blurry because the plane started to move, but you can tell the CO2 rose to 2343, then 2351 ppm.

8/ I think the ventilation system started bringing in outdoor air when the plane began taxiing but that it took a couple minutes for the CO2 to begin to decline. Two minutes after peaking at 2351 ppm, it had decreased to 2026, and two minutes after that it was 1738.

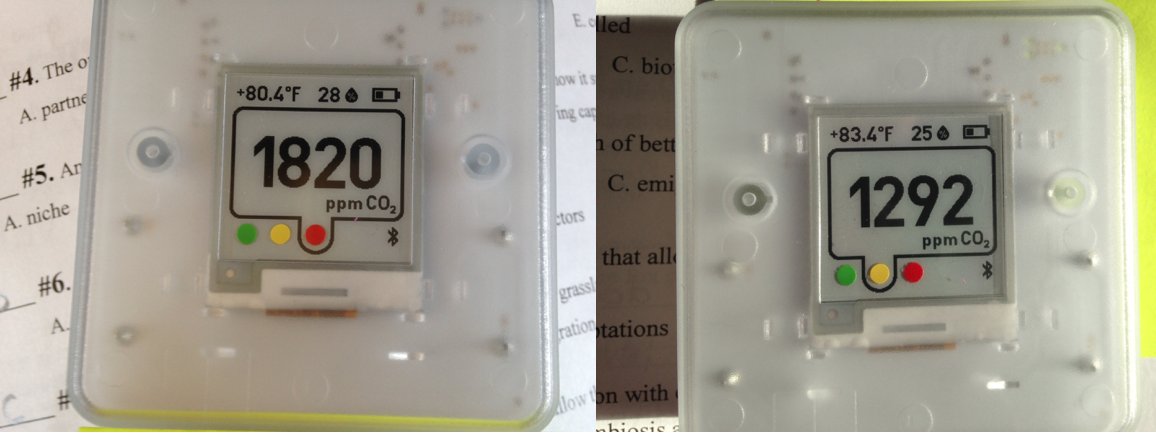

9/ By the time we took off the CO2 was around 1400 ppm, and it stayed right around that level for the entire flight.

10/ Chicago’s O’Hare Airport appeared to have quite good ventilation. The CO2 level stayed in the low-600 range where I was. I did not venture into the crowded cafeteria area nearby, where I imagine the levels were significantly higher.

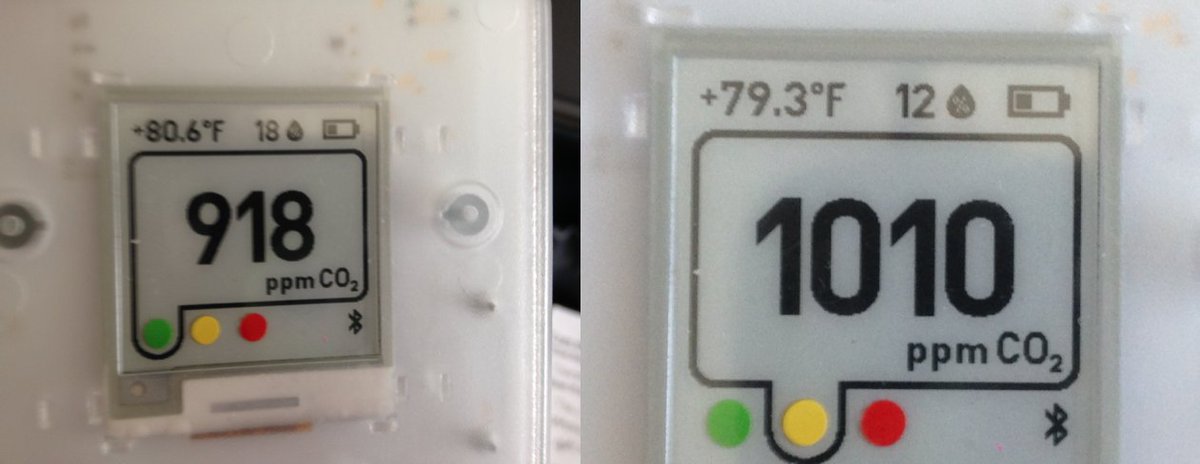

11/ The next flight was to Rochester, MN, also on American Airlines. Immediately after boarding, the CO2 was already at 2096 ppm.

12/ Five minutes later, the CO2 concentration had risen to 2393 ppm, and in the next two minutes it rose further, to 2548 before peaking at 2650 ppm.

13/ At this point there was a revving noise, and CO2 levels started to decline, falling to 1820 ppm seven minutes later. 20 minutes after the peak 2650 reading, CO2 had declined to 1292 when we started taxiing.

14/ After taxiing for several minutes, we stopped. CO2 once again rose, but only to 1546, after which the plane started rolling again and levels declined.

15/ During this flight, which seemed equally crowded as the first flight and on a similarly small plane, CO2 concentrations were lower, ranging between 900-1030 ppm. Notably, relative humidity got as low as 12% later on in the flight.

16/ The Rochester Airport wasn’t very crowded, but with CO2 at 492 ppm, it still must have had good ventilation. Doors about 10 meters away likely helped.

17/ I’ll stop there for now. Later I’ll add info about the CO2 levels at Mayo Clinic and our hotel. Our return flights, again with a layover at O’Hare, are later today, and it will be interesting to see how they compare.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh