We’ve talked a bit about Army training and how the history threads in this series are helping set the stage for the 1941 GHQ Maneuvers, which we will discuss later this year. But we haven’t talked much about changes to Army Doctrine.

The 1941 GHQ Maneuvers in Louisiana and the Carolinas were used to help develop and test Combined Arms Doctrine. @usacactraining @TRADOC @USArmyDoctrine @USARMYMCTP @MCTP_OGAlpha @MCTP_OGBravo @MCTP_OGCharlie @USArmy_CALL @ArmyUPress

During World War I, the US was still very much unprepared for modern war, and that meant “modern” at that time. By World War II, we would be facing a new definition of “modern war”.

Our WWI Doctrine was outdated and we had virtually nonexistent experience in the command of large forces. The coordination of arms and services was largely a matter of theoretical conjecture.

It would take 1½ years from the declaration of war to create a field army capable of mounting an offensive on the Western Front, and even in the final major operation of WWI, the Meuse-Argonne offensive, our amateurism was still painfully obvious. We lost 26,000 soldiers. @USAHEC

There are reasons for this. Our planners were overly optimistic and set unrealistic goals. Our Logistics weren’t great. Our Communications weren’t great.

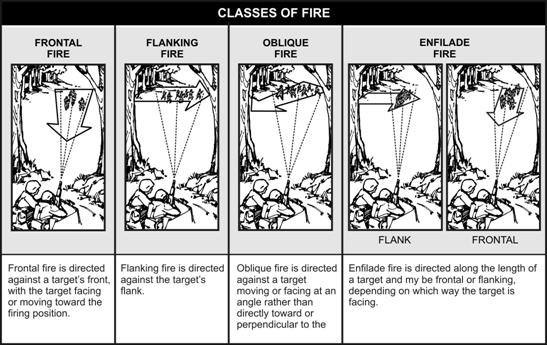

Tactical commanders resorted to frontal attacks, not quite mastering the use of support weapons. Some division commanders had to be replaced as they were just not up to the task.

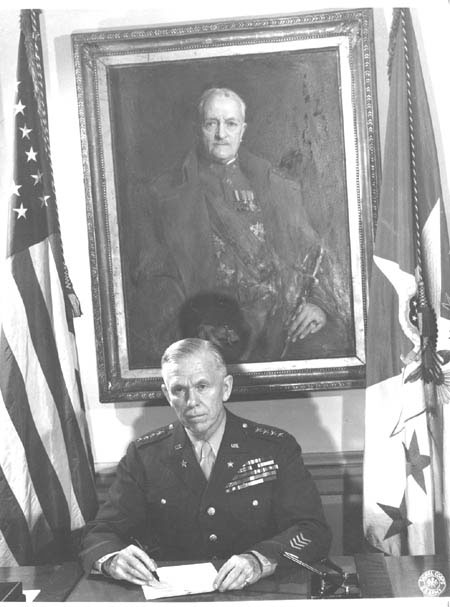

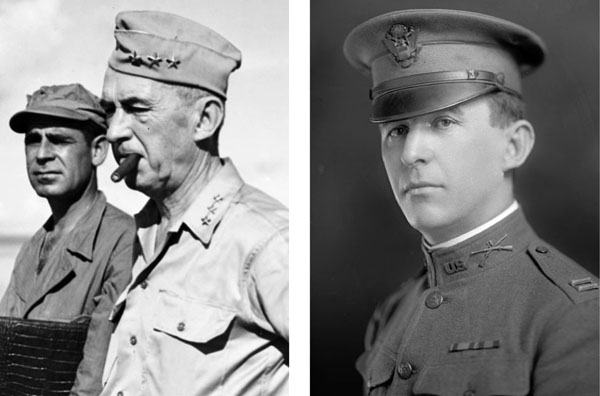

George C. Marshall was a Colonel during WWI. He would become the US Army Chief of Staff some 20 years later.

During the Interwar Years, the Army, as a whole, was inadequately funded, much of the force was skeletonized, there was no real increase in, let alone maintenance of, readiness.

The Regular Army and Army National Guard engaged in periodic maneuvers but they were little more than play-acting.

When Germany invaded Poland in September of 1939, the @USArmy ranked 17th in the world. Seventeenth.

We had only three functioning infantry divisions, all at roughly half-strength. Very few tactical units larger than a battalion. The US Army Air Corps had fewer than 20,000 men, and even though there were 62 tactical squadrons in the Air Corps, all the aircraft were obsolete.

There were no corps. No field army headquarters. The National Guard could barely keep their 18 divisions functioning at “maintenance-strength”.

Even though we all know the outcome of the war now, it all seems pretty grim when we consider these facts.

Most of the growth to the US military occurred after the attack on Pearl Harbor, with the official US declaration of war driving that progress. But the rapid expansion we were able to achieve was made possible by the pre-war mobilization efforts we’ve been talking about.

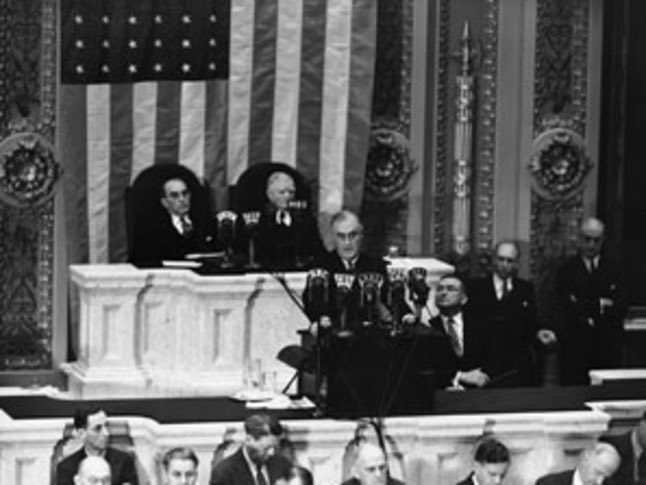

“A reasonable start date to posit for the onset of protective mobilization is 8 September 1939, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt proclaimed a ‘limited national emergency… for the purpose of strengthening our national defense within the limits of peacetime mobilizations’.”

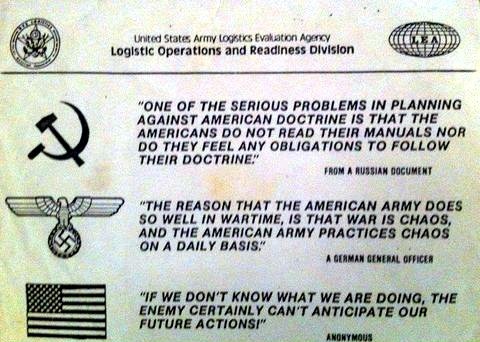

To replace old US Army Doctrine, we borrowed from the Germans in the 1930s. @USArmyDoctrine @USArmy_CALL @USACGSC @DMH_at_CGSC @us_sams

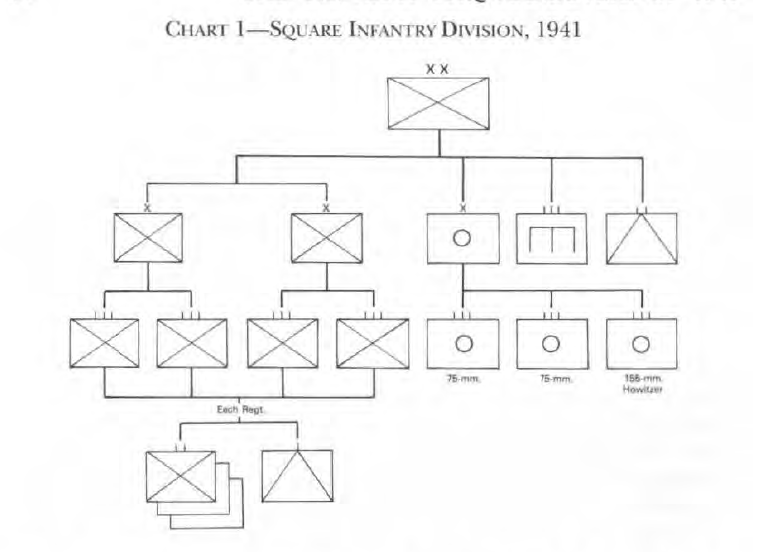

In 1937, the Infantry Chief, Major General George A. Lynch, decided to discard the old Square Division scheme. Used in WWI, Square Divisions were largely focused on trench warfare and basically tailor-made for attrition.

MG Lynch wanted to provide each Infantry company and battalion with weapons sufficient to establish their own base of fire – mortars, machine guns, etc.

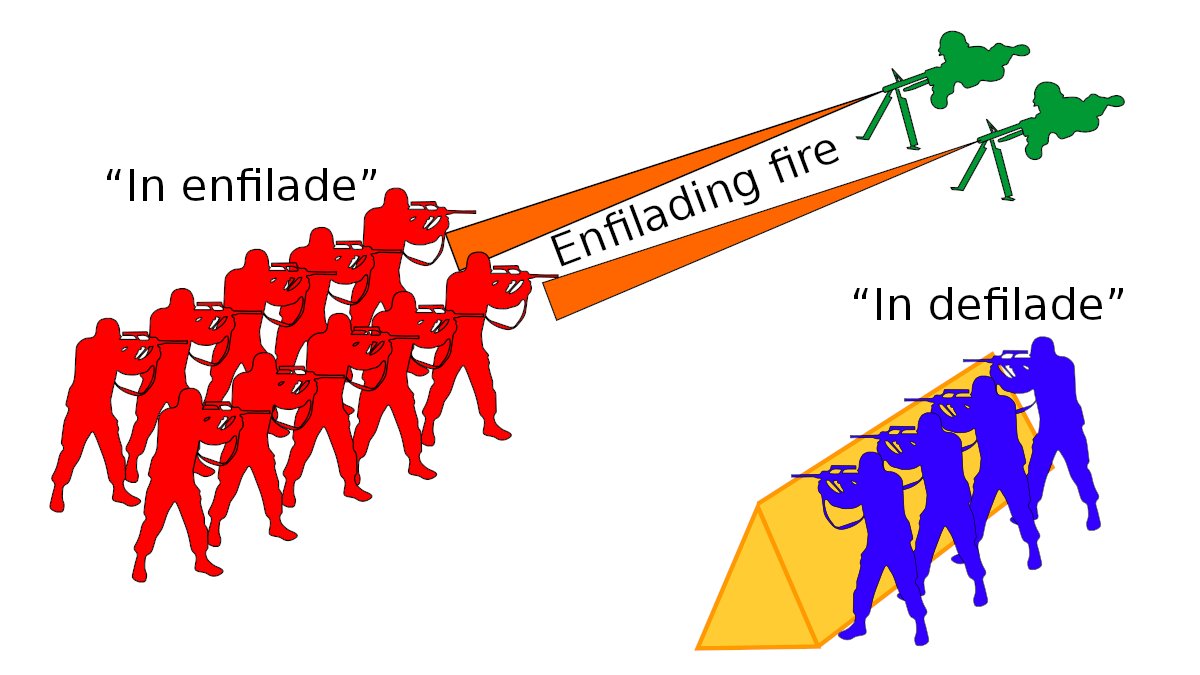

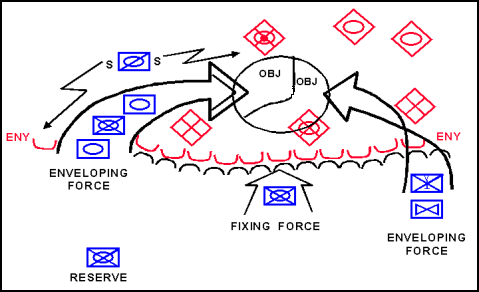

Basically, the soldiers would take advantage of frontal or flanking positions that allowed them to fire at more of the enemy soldiers. They could secure one objective and move on to the next.

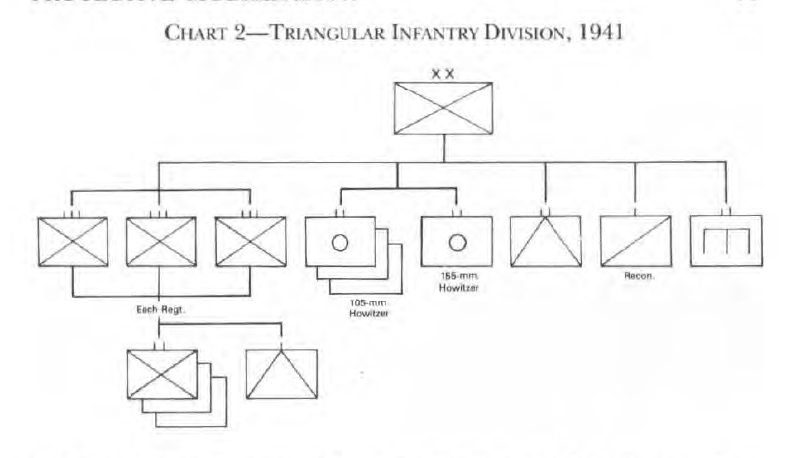

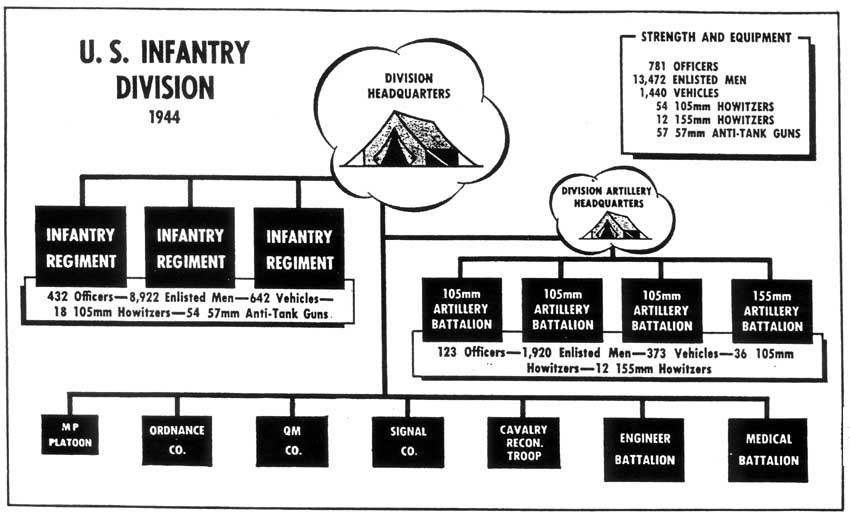

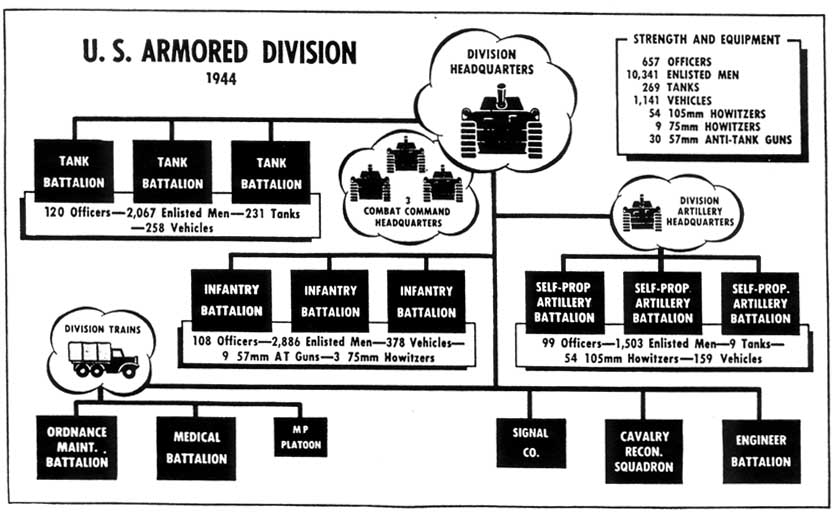

In 1939, George C. Marshall would have the @USArmy adopt Triangular Divisions which could better support this new Doctrine.

Triangular Divisions were also borrowed from the Germans – nearly every echelon within the division would now possess maneuver elements and fire support. Our Doctrine and our Army organizational structure were starting to mesh nicely.

Each echelon could establish its own base of fire using both direct and indirect fire support – fix the enemy with one maneuver element, find its flank with a second, and maintain a third in reserve. @PatDonahoeArmy @FortBenning

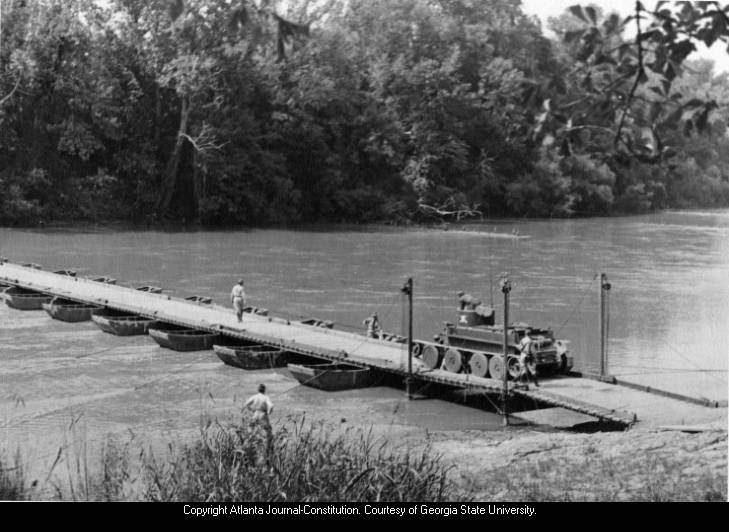

Triangular Divisions also replaced animals with motorized transport, although Infantry would still often travel on foot.

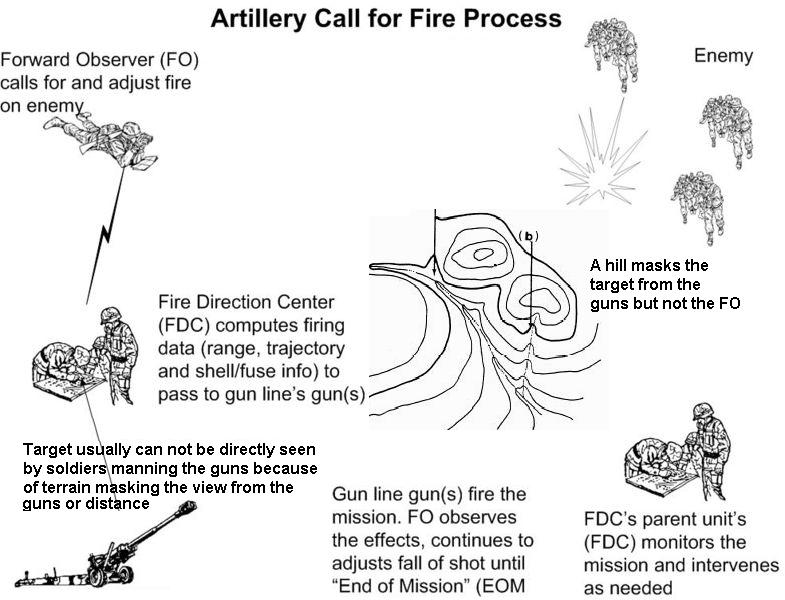

Artillery Doctrine had evolved since 1918 as well, and the move to a Triangular Division saw accuracy, responsiveness, and flexibility supplant sheer volume as Measures of Effectiveness (MOEs). @USAFAS

In Triangular Divisions, there were three battalions of light Artillery which could be attached to Infantry regiments to create “regimental combat teams”, and a battalion of medium Artillery for general support. @USAFAS

Improvements in communications and advances in techniques of observation and fire direction allowed Field Artillery to decentralize its batteries for maximum responsiveness, while still retaining its ability to mass fires when needed. @USAFAS @USArmyDoctrine

To keep the Triangular Divisions leaner (about 15,000 soldiers), the War Department “streamlined all support and service elements not essential to the Division” and pooled them in reserve at higher echelons until needed. @SCoE_CASCOM @CASCOM_CG

The new Army Doctrine and organization/force structure helped drive procurement and development of many “less glamorous” items that the Army needs, not just weapons and vehicles but things like water purifiers, cooking ranges, and food containers.

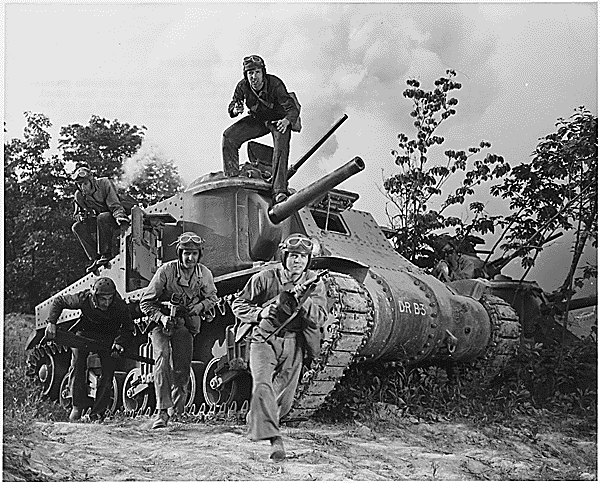

In March and April of 1940, the @USArmy assembled and tested IV Corps at @FortBenning, which was the first corps to take the field since 1918. IV Corps was comprised of 1st Division, 5th Division, and 6th Division (all in the new Triangular structure). @1stArmoredDiv

In May of 1940, IV Corps traveled to Louisiana to face off against IX Corps, which included 2nd Division and @1stCavalryDiv – this would be the first-ever Corps-vs-Corps maneuvers in @USArmy history. @USArmyCMH @DMH_at_CGSC @us_sams @USACGSC @USArmy_CALL

By June of 1940, solid progress was clearly being made, despite nearly 20 years of inadvertent neglect. The Triangular Division had been adopted and tested, and @USArmy commanders were gaining valuable experience in using Triangular Divisions under field conditions.

New and modern equipment were still scarce but MG Walter C. Short, then IV Corps commander, commented at the end of the Spring 1940 maneuvers that the equipment problem would be solved within a year or so, provided Congress continued liberal appropriations.

If you're just tuning in or you've missed any of the previous threads, you can find them all saved on this account under ⚡️Moments or with this direct link twitter.com/i/events/13642…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh