The legal issue here is this.

https://twitter.com/paulbranditv/status/1390775379686735875

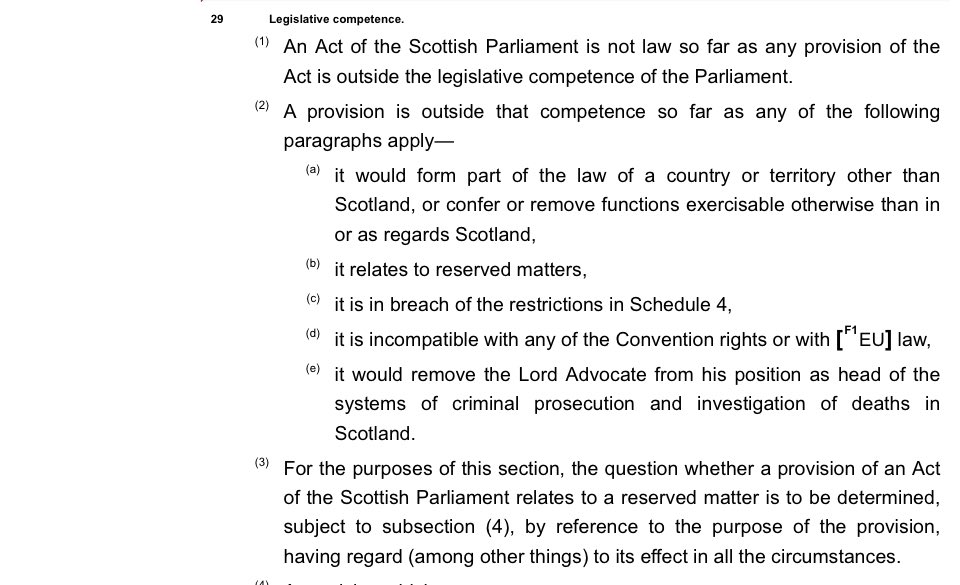

The Scotland Act 1998 says that legislation is outside the competence of the Scottish Parliament if it “relates to reserved matters”.

See section 29(3) in the above quote for some help as to what “relates to” means. You look at the purpose of the legislation at issue and its effect in all the circumstances.

So the question is this: does 🏴 Parliament legislation providing for a referendum on independence “relate to” the Union, looking at the purpose of the legislation and having regard to all the circumstances?

Put that way, it isn’t obvious to me how it could convincingly be argued that legislation for such a referendum would be within competence: what is the purpose of a referendum on independence other than to affect the Union of the Kingdoms?

But one good rule of thumb in legal commentary is that it’s dangerous to call any legal dispute until you see the arguments being run. So let’s see.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh