NEW: latest update on B.1.617.2 in UK

Story: ft.com/content/ce0730…

Thread:

First, today’s Sanger data on variants at local level. On the surface, this doesn’t look good. Cases of non-B.1.617.2 are in decline, but those red peaks are the variant sending overall rates climbing

Story: ft.com/content/ce0730…

Thread:

First, today’s Sanger data on variants at local level. On the surface, this doesn’t look good. Cases of non-B.1.617.2 are in decline, but those red peaks are the variant sending overall rates climbing

To state the obvious: that pattern is not what we want to see, and if things keep going in that direction, we could see national cases rapidly climb again.

But there are a couple of reasons to pause before assuming we’re going to see those peaks steepen and proliferate.

But there are a couple of reasons to pause before assuming we’re going to see those peaks steepen and proliferate.

First, the Sanger data is sequences with specimen date before May 8.

We’ve got more days of data since then. It’s not broken down by variant, but it can show us what’s happened to total cases in those areas since May 8.

Answer: growth rates have slowed, in some cases reversed

We’ve got more days of data since then. It’s not broken down by variant, but it can show us what’s happened to total cases in those areas since May 8.

Answer: growth rates have slowed, in some cases reversed

That’s also apparent in a plot of B.1.617.2 prevalence vs overall weekly growth.

The diagonal upward trend here is becoming less clear. Some areas where B.1.617.2 is though to be dominant are seeing cases fall. Many areas where little B.1.617.2 has been detected are seeing rises

The diagonal upward trend here is becoming less clear. Some areas where B.1.617.2 is though to be dominant are seeing cases fall. Many areas where little B.1.617.2 has been detected are seeing rises

It’s certainly very much possible that there *is* still a link between the two (which would suggest greater transmissibility of B.1.617.2).

A lot of local authorities have had very few cases sequenced, meaning we don’t really know how prevalent the variant is in many areas.

A lot of local authorities have had very few cases sequenced, meaning we don’t really know how prevalent the variant is in many areas.

But between the slowdowns and reversals in B.1.617.2 hotspots, and the increasingly fuzzy relationship between its prevalence and overall growth, that link feels less clear today than it has done to date.

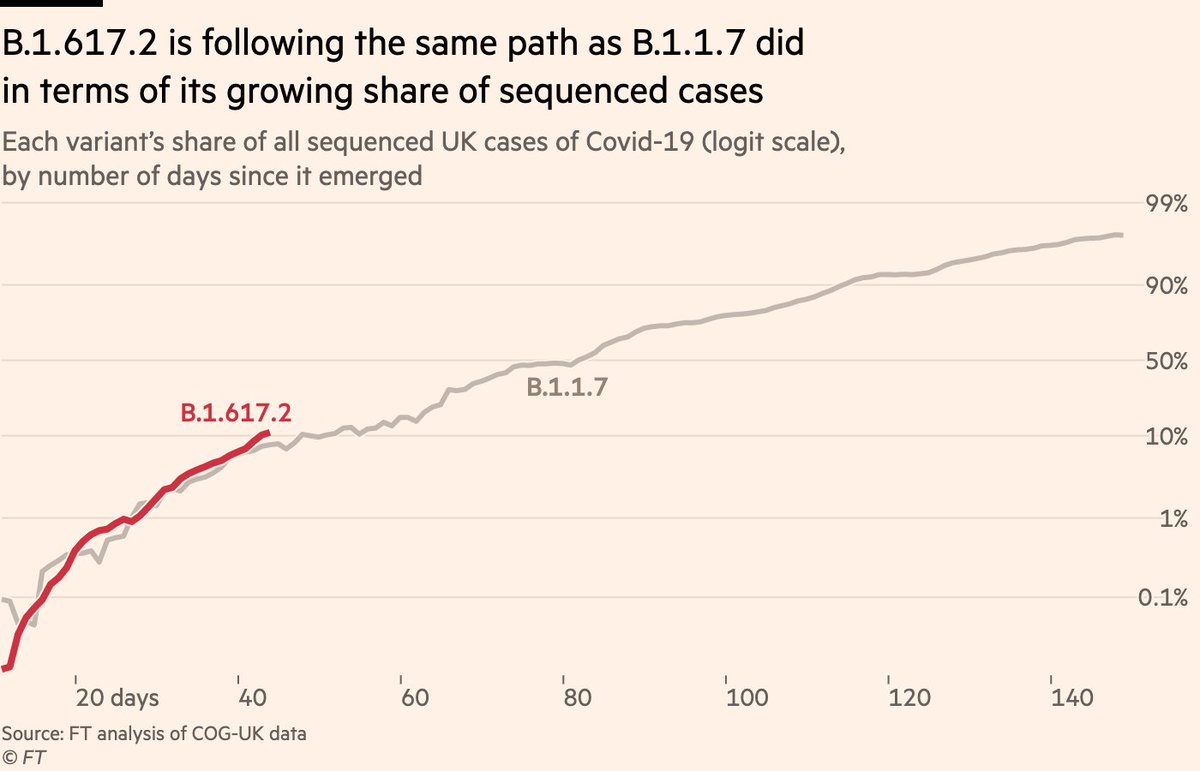

This would be in line with what some, including @arambaut @andrew_croxford @mugecevik have theorised, which is that the higher early growth rates seen from B.1.617.2 may be caused by other factors than an innate transmissibility advantage:

https://twitter.com/andrew_croxford/status/1393258338067091461

One possibility is that the contrast between very very low rates of the virus in early April, vs the sheer volume of cases imported from India, caused travel-linked clusters to have an outsized impact on overall rates.

Essentially, you have a scattering of clusters sparked by the introduction of B.1.617.2 from abroad. These are concentrated in highly vulnerable communities: low vaccination rates, dense living conditions etc, so they initially spread relatively efficiently within these areas.

After a couple of generations of transmission, they lose momentum. In some areas (perhaps Sefton) they burn out entirely and cases recede back towards their baseline level. In others, conditions are ripe for a longer initial burst, but then that gradually loses momentum.

This would initially look like a transmissibility advantage, but when you consider how low rates were in Bolton in early April (20 confirmed cases per day in a town of ~200,000 people), it’s arguable B.1.617.2 was never really "in competition" with B.1.1.7 in any meaningful sense

And as pointed out by @mugecevik, this pattern — imported variant causes spikes in prevalence that then peter out — is not new. Some of you may remember 20A:EU1 (originated in Spain) that arrived last summer to much fanfare but never took hold here

https://twitter.com/mugecevik/status/1394275407885709317

To be clear, the above is just one theory. It remains entirely possible B.1.617.2 is more transmissible and could fuel a UK resurgence.

But so far, that’s not happening. A brief rise in cases last week now appears as a small bump, possibly caused by bank holiday testing patterns

But so far, that’s not happening. A brief rise in cases last week now appears as a small bump, possibly caused by bank holiday testing patterns

And here’s an update of case rates by age in some of the areas of concern, again showing that the rise has been concentrated among younger, less-vaccinated groups while cases among older groups remain at low levels.

So I’d continue to suggest that we all keep a very close eye on this, but I don’t feel more worried today than I was before.

And regardless, any prolonged rise in cases anywhere in the UK is worthy of investigation, regardless of the role B.1.617.2 may be playing.

And regardless, any prolonged rise in cases anywhere in the UK is worthy of investigation, regardless of the role B.1.617.2 may be playing.

Finally, I’d strongly encourage people to listen to what @kallmemeg and co at @PHE_uk have to say in their next variant update later this week, where we can also expect updated S-gene figures. Those technical reports are rapidly becoming indispensable gov.uk/government/pub…

And one addendum:

I think that in some cases, the focus on B.1617.2 is providing more heat than light.

What really matters is whether more people are getting sick or hospitalised, not the number or % of B.1.617.2 sequences.

I think that in some cases, the focus on B.1617.2 is providing more heat than light.

What really matters is whether more people are getting sick or hospitalised, not the number or % of B.1.617.2 sequences.

If a new variant is what tips a country into a new, lethal wave, it’s important to spot it & to use that understanding to turn things around.

But at the moment it feels like there’s a lot of "B.1.617.2 numbers are up!" without reference to whether it’s causing things to worsen.

But at the moment it feels like there’s a lot of "B.1.617.2 numbers are up!" without reference to whether it’s causing things to worsen.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh