What does it take to make a successful #Eurovision song? And why is it that the UK can never seem to catch a break at a contest that it used to habitually win? If you'll indulge me in a little light musical theory, I have a possible explanation...

PART I: The Key

Of all the rakes that the UK consistently stamps on at Eurovision each year, the key of its songs is the biggest and spikiest. Despite the sound of the contest having changed dramatically since the UK's heyday in the 80s + 90s, we remain weirdly stuck in our ways.

Of all the rakes that the UK consistently stamps on at Eurovision each year, the key of its songs is the biggest and spikiest. Despite the sound of the contest having changed dramatically since the UK's heyday in the 80s + 90s, we remain weirdly stuck in our ways.

Since 2000, the overwhelming majority of Eurovision winners have been written in a minor key. Not only have minor keys won 3x more than major ones, major keys have come also dead last nearly 3x more than minor ones too...

To quickly explain major/minor keys – major keys are generally considered to be bright, cheering, optimistic ones; minor keys tend to be sad, moody and dark.

One helpful example:

The wedding march = major key

The funeral march = minor key

One helpful example:

The wedding march = major key

The funeral march = minor key

CAVEAT: Key isn't the *only* thing that can make a song sound happy or sad. Tears In Heaven is in a major key and is definitely sadder than Boogie Wonderland. Speed, instrumentation, performance, lyrics all play a part, but major=happy/minor=sad is a useful rule of thumb.

Over the last 20 years there's been a 180˚ shift in Eurovision – from major key dominance to minor key.

• In 2000, 18 of the 24 songs were in a major key; 6 minor

• In 2019, 19 of the 26 songs were minor; 7 major

• In 2000, 18 of the 24 songs were in a major key; 6 minor

• In 2019, 19 of the 26 songs were minor; 7 major

I'm not cherry picking those particular years:

• 2001 had 16 songs in a major key v 7 minor

• 2018 had 18 songs in a minor key v 8 major

This switchover started picking up steam around 2002 and now - in 2021 - you can barely move for minor key entries.

• 2001 had 16 songs in a major key v 7 minor

• 2018 had 18 songs in a minor key v 8 major

This switchover started picking up steam around 2002 and now - in 2021 - you can barely move for minor key entries.

Obviously, if you have three times as many minor songs in a contest you'd expect minor songs to win three times more. Stands to reason, right? But looking at the full scoreboard paints a very clear picture. Here are some graphics I prepared earlier...

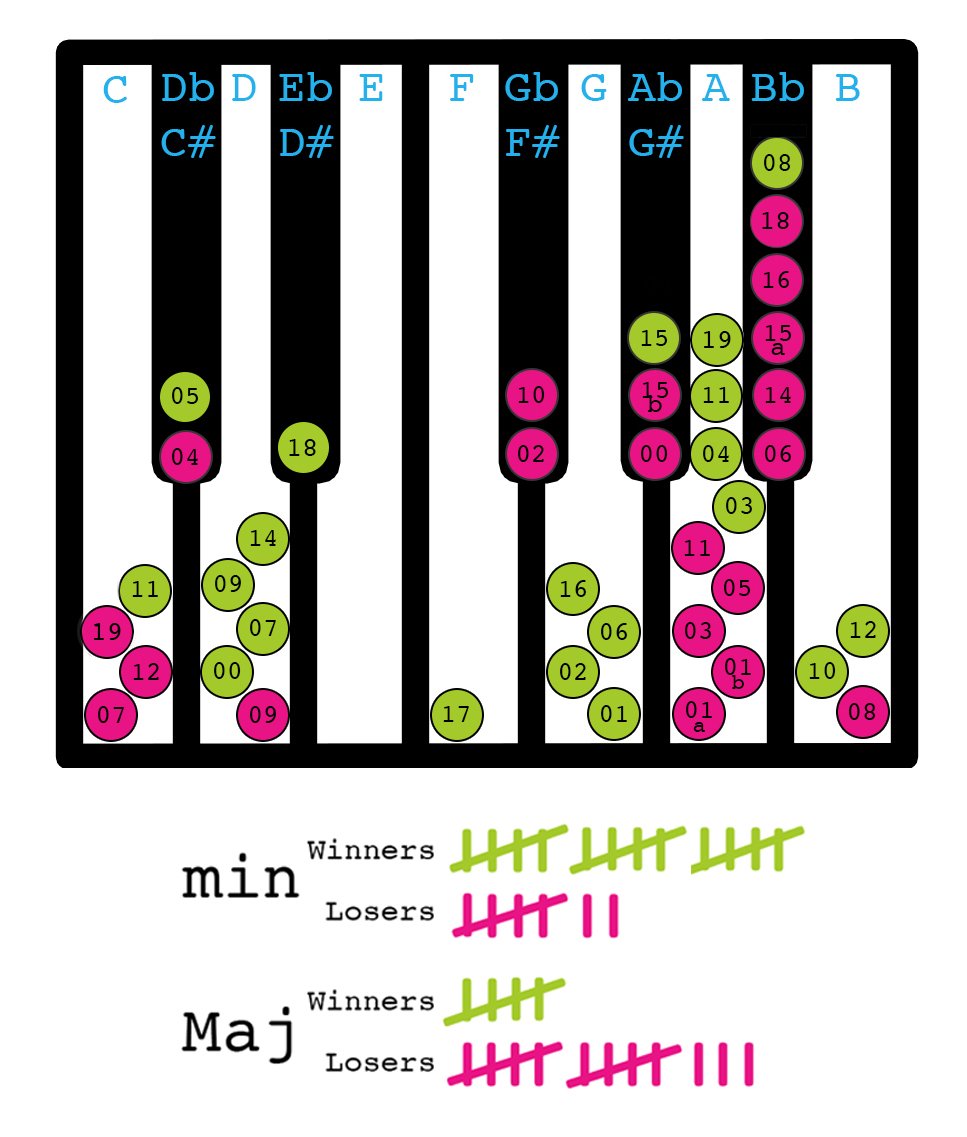

Fig. 2: The spread of minor keys v major keys at the 2019 Eurovision Song Contest, with their respective results superimposed

The bottom of the scoreboard is positively sodden with major key entries. A couple of them tend to do alright (it's nice to have a little levity in what can otherwise be an onslaught of sullenness) but the prevailing theme? MAJOR KEYS ARE CONCRETE BOOTS.

So as the overall sound of the contest has drifted definitively from major to minor over the last two decades, what has the UK been doing?

If you want to hear how steadfast the UK sound has been as the contest changed around it, I spoke about this on Radio 4’s More Or Less. Whoever produced the segment expertly demonstrated the point by blending our 2019 entry into our 1997 as I spoke. It is SEAMLESS.

NB: That whole episode is here, if you want to hear me fumbling about on one of Radio 3's proper grand pianos as I'm trying to talk... bbc.co.uk/programmes/p07…

This is what the minor/major weighting looks like for 2021. You'll notice bookies' favourites Italy, France, Malta, Iceland, Switzerland, Ukraine (etc) all in the left hand column, while long-shot outsiders Germany and the UK are on the right.

PART II: Tempo

Another foundational element of a good pop song is its beat. Looking back over the last 20 years of winners and losers, a remarkable pattern starts to emerges in the tempo markings – not so much in what helps a song to win, but what can kill its chances...

Another foundational element of a good pop song is its beat. Looking back over the last 20 years of winners and losers, a remarkable pattern starts to emerges in the tempo markings – not so much in what helps a song to win, but what can kill its chances...

Two clusters of unluckiness emerge when you inspect all the songs that have finished in last place since 2000. Weirdly, in the last decade, all but one of the losing entries has been paced at ~128bpm or ~85bpm (beats per minute).

128 is a fascinating number in pop music because it's a point where a few important staples of timing, structure and tempo all intersect. Not to get too far into the weeds, but to make sense of the next bit you need to know that most pop is written in 4/4 (a "1, 2, 3, 4!" count).

• Eurovision songs have an upper limit of three minutes

• 3 mins of an 128bpm count creates exactly 96 bars of 4/4

• As 96 is divisible by 4, 8, 12 and 16 (the building blocks of pop music phrasing) this *should* create an endlessly flexible, foolproof template for pop songs

• 3 mins of an 128bpm count creates exactly 96 bars of 4/4

• As 96 is divisible by 4, 8, 12 and 16 (the building blocks of pop music phrasing) this *should* create an endlessly flexible, foolproof template for pop songs

And yet...

Eurovision audiences have an uncanny knack for rooting out songs in 128bpm and tossing them binwards. Obviously they don't sit in front of the TV with a metronome on hand (they're not all like me) but they clearly have a natural ear (/distaste) for this cookie-cutter template...

The maths behind 84/85bpm turning people off is beyond my ken, I'm afraid – but you can't argue with results...

PART III: The Key Change

There's a really persistent idea in the UK that key changes are the backbone of Eurovision. They're a staple of the drinking games, they're always slap bang in the centre of any Eurovision Bingo Card – but they're actually surprisingly rare these days.

There's a really persistent idea in the UK that key changes are the backbone of Eurovision. They're a staple of the drinking games, they're always slap bang in the centre of any Eurovision Bingo Card – but they're actually surprisingly rare these days.

In the last 20 Eurovision contests, only three songs with a key change have won, whereas five songs with a key change have come dead last (including one hugely ambitious one that spanned SIX semitones and fell flat on its face...)

NB: I honestly have to sit at the piano and check this six-semitone key change every year, because I still can't believe it's real. She just bounces from Ab Major to D Major in the middle of the song for no real reason...

The reason we've fallen under this collective delusion that key changes are somehow an essential Eurovision element? Much like major keys, they were everywhere you turned in 2000 – but have since fallen wildly out of fashion...

• In 2000, 16 out of the 24 songs featured a key change of some description (Ireland even managed to cram two into theirs...)

• In 2019, just 4 out of 26 did.

• In 2019, just 4 out of 26 did.

Again, I'm not just cherry picking years that tell a good story:

• In 2001, 12 of the 23 songs featured a key change

• In 2018, just 2 of the 26 finalists did

• In 2001, 12 of the 23 songs featured a key change

• In 2018, just 2 of the 26 finalists did

There are three songs with key changes in this year's final. There were six at the start of the week, but half of them didn't qualify out of the semis – including two that made three-semitone leaps (pretty meaty in terms of key changes): Australia and North Macedonia.

Thankfully, key changes are one bad habit the UK has largely managed to shake. With one brief relapse...

Anyway: if you're interested in this sort of thing, I write a companion guide for Popbitch each year – vaguely in this vein, but with more jokes and a bit more swearing... popbitch.com/the-popbitch-g… #Eurovision

I'll try to tweet a bit of theory stuff about each song as the postcard is on, and then I'll probably resort to making crap jokes while the acts are actually performing.

Fig 4. The spread of minor keys v major keys at the 2021 Eurovision Song Contest, with their respective results superimposed

All of the Top Ten = minor keys

All of the Bottom Four = major keys

All of the Bottom Four = major keys

(Miscounted in yesterday's image; Spain snuck into the minors. It's Eb Major.)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh