What does it mean to belong somewhere? #APAHM on.natgeo.com/3vkZHDn

"That question of belonging is at the heart of our essay exploring how Asian Americans across generations navigate the balancing act of their identities and carve out a place for themselves in this country," writes Elaine Teng (@elteng12) email.nationalgeographic.com/H/2/v600000179…

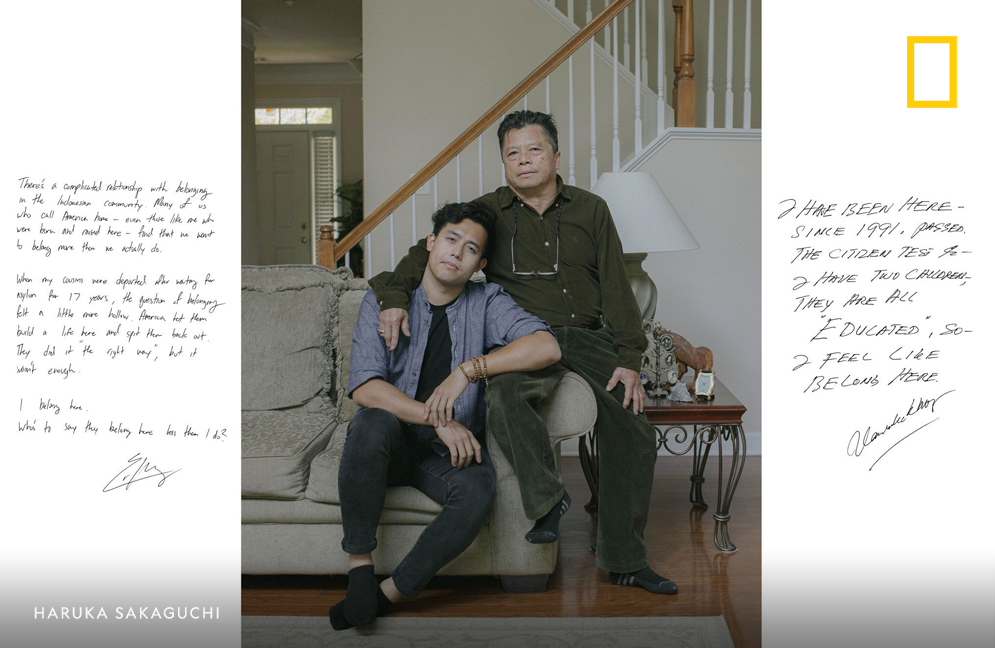

Elaine and photographer Haruka Sakaguchi (@hsakagphoto) met with over a dozen families in the Atlanta area, the site of the deadliest anti-Asian hate crime in the last year, to ask what belonging means to them, and what their American Dream looks like.

Handoko Khong, right, left Indonesia in 1991 to escape religious and ethnic persecution. For the last three years, he and his son Eric have been helping to care for two younger relatives whose parents were deported after living in the U.S. for 17 years.

Ramanaresh Pathak poses w/ his granddaughters Ishani & Kiran. Born in India, he lived in England for 20 yrs then moved to New Jersey in 1987 because he believed his kids would receive better educations. "I don’t feel connected to any place except wherever [my grandchildren] are."

Hannah Son, right, tries to imagine what it was like for her mother, Christina, to leave Korea at 23 to start a new life in a country where she didn’t speak the language and didn’t know anyone. "I can’t fathom that," she says.

Kylie Wen, right, is the daughter of Taiwanese-American Shawn and his wife, who is Black. They regularly teach their daughter about Black and Asian history so she can understand her heritage—and the potential pushback.

Loan Tran, right, and her siblings cried the first few months their parents moved them from a tight-knit Vietnamese community in Massachusetts to rural Georgia. Both of her parents fled the Vietnam War. "They tethered their hands together and made sure they were never separated."

Kathryn Iwasaki, right, is Chinese on her mother’s side and Japanese on her father’s. Her paternal grandmother survived the atomic bomb in Hiroshima but lost three siblings, while her grandfather lived through an internment camp in Arkansas.

Urvashi Gadi poses with her daughters Prisha, left, and Akriti. She moved to the U.S. from India in 2001 to be with her husband. She remembers how hard it was then to even get small things done, like finding a handyman, and today she still considers returning.

Ruth McMullin, right, whose Black father and Vietnamese mother fled Vietnam, grew up in small-town Alabama where she was one of the only biracial children. She tells her daughter Anh, who has albinism, not to let other people’s perspectives define her.

Read about other Asian American families across generations as they reflect on the ways they hold on to their cultures while finding a place in America. on.natgeo.com/3vkZHDn #APAHM #AAPIHM

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh