#apaperaday Today’s pick is published in @FASEBorg journal by Chu et al on the long term effects of expression of a mini-dystrophin in an mdx mouse background.

Duchenne is caused by lack of dystrophin. Gene addition therapy aims to restore dystrophin production in muscle and heart by providing a copy of the gene code using adeno-associated viral vectors (AAV). However, AAV capacity is too small for complete dystrophin.

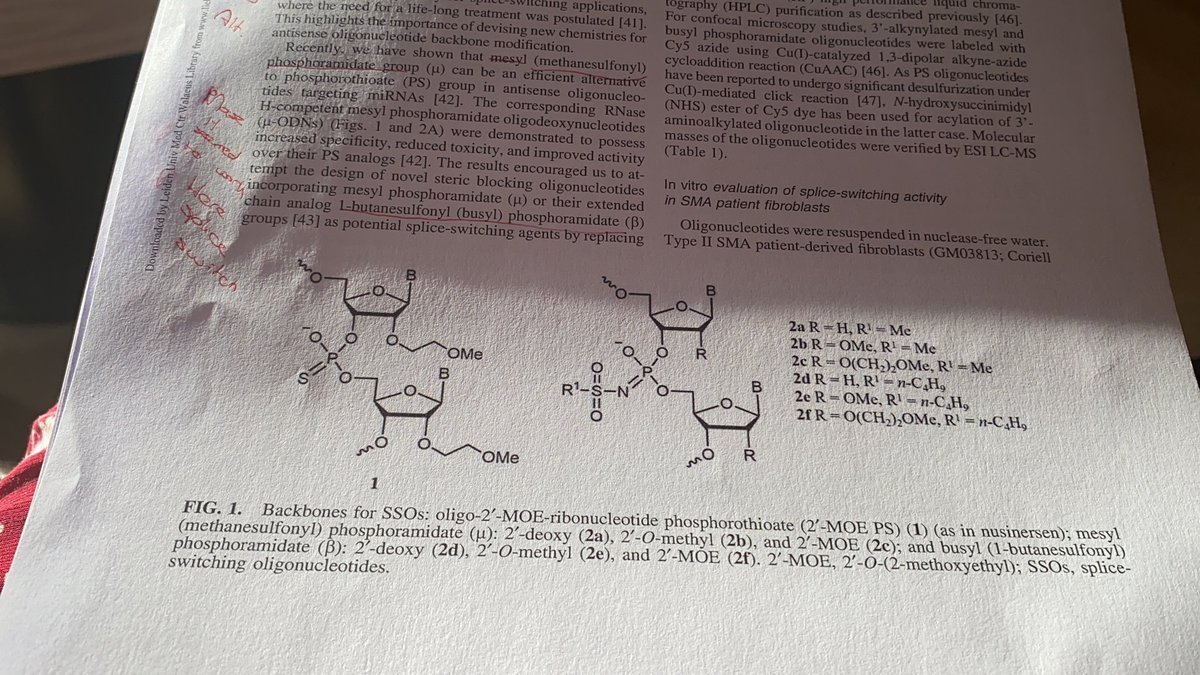

Thus several shorter dystrophins (microdystrophins) have been produced containing only most crucial domains for which the gene code fits inside AAV vector. 3 are in clinical trials, containing N-terminal actin binding, cysteine rich domain and 4-5 spectrin repeats and 2-3 hinges

Here authors have another microdystrophin: N-terminal actin binding, 2 hinges, 4 repeats and a longer cysterin rich/C-terminal domain. This contains also the part that binds to syntrophin. Authors call it mini-dystrophin but size is equally small as the micro-dystrophins

To test functionality of this human micro-dystrophin in muscle authors generated transgenic mice in a mouse dystrophin-negative background. This means the mice expressed the microdystrophin from conception (not comparable to AAV delivery at later time point).

The microdystrophin was expressed in all skeltal muscle fibers, but not in heart and at low levels in diaphragm. this is due to the promoter used (the volume button that genes have - the one used (modified CK) expresses in this manner).

Microdystrophin restored associated proteins (sarcoglycans and dystroglycans) and nNOS as well. The nNOS binding is due to indirect binding via syntrophin (the domain for direct nNOS binding is not present in this microdystrophin).

Microdystrophin restoration resulted in lower need for regeneration (less centrally located nuclei) & increased membrane stability (less Evans blue dye uptake). It resulted in increased muscle strength and endurance until 20 months of age. Muscles were less hypertrophic than mdx.

Authors mention 2 limitations: 1) the promotor used needs to be changed for clinical application because also heart and diaphragm needs to be targeted. 2) the mdx model is mildly affected, so unclear how functional this dystrophin is in more severely affected model as yet.

My own comments: authors use a transgenic model and show long term effects (20 months is long term for mice). However, this is not comparable to AAV gene transfer, where not all muscles are transduced and there is dilution of transgene with time.

This limitation is not mentioned by the authors which I find surprising. AAV gene therapy for Duchenne has overcome several issues and body wide delivery of skeletal muscle is now possible. However, transduction is not 100% and we know with time there will be loss of transgenes.

What we do not know is how long this will take (hopefully decades). This study shows the microdystrophin is functional in mouse but I am not surprised effects are long term given that this is a transgenic model. Hope to see AAV preclinical studies from this group next.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh