How Tony Blinken’s Stepfather Changed the World—and Him

He survived the Nazi death camps of Majdanek, Auschwitz and Dachau, escaping at the age of 16. At the request of Leonard Bernstein politico.com/news/magazine/…

He survived the Nazi death camps of Majdanek, Auschwitz and Dachau, escaping at the age of 16. At the request of Leonard Bernstein politico.com/news/magazine/…

The lawyer, a famed Holocaust survivor named Samuel Pisar, spoke Russian, among other languages.

Samuel Pisar at the Auschwitz Memorial in front of a map showing different locations from which people were deported to Auschwitz.

He was 10 years old when the Germans and Soviets invaded his native Poland in 1939. In the ensuing years, he and his family lived under Soviet occupation, then were temporarily shunted to a ghetto by the Nazis.

Pisar survived roughly four years in labor and death camps—including Majdanek, Auschwitz and Dachau — often through sheer instinct. In one instance, after being chosen for a group marked for the gas chamber, the boy grabbed a nearby pail and brush and began scrubbing the floor

as if that was why he was there. The ruse worked. He lived. Pisar, then 16, and two close friends from the camps who escaped with him—Ben and Niko—soon found themselves working as black marketeers in the American occupation zone of Germany, trafficking in such goods as

cigarettes and coffee. “If I had stayed in Europe, I might have become a terrorist or a gangster,” he later said.

He would receive degrees from the University of Melbourne, Harvard and the Sorbonne, preludes to an illustrious career in law that saw him advise people ranging from

He would receive degrees from the University of Melbourne, Harvard and the Sorbonne, preludes to an illustrious career in law that saw him advise people ranging from

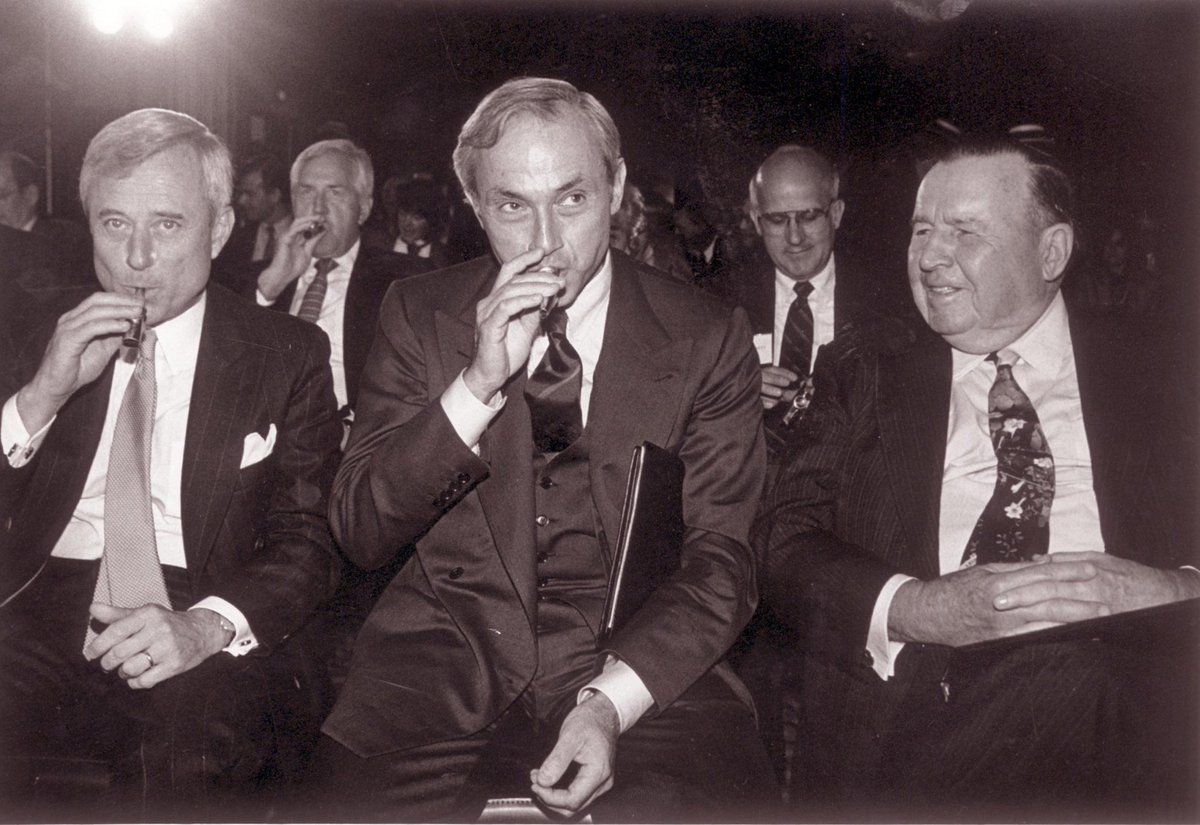

From left-right: Leah Pisar; Samuel Pisar and wife Judith Pisar, chair of Arts France; Antony Blinken; Blinken’s wife, Evan Ryan. | Bertrand Rindoff Petroff/Getty Images

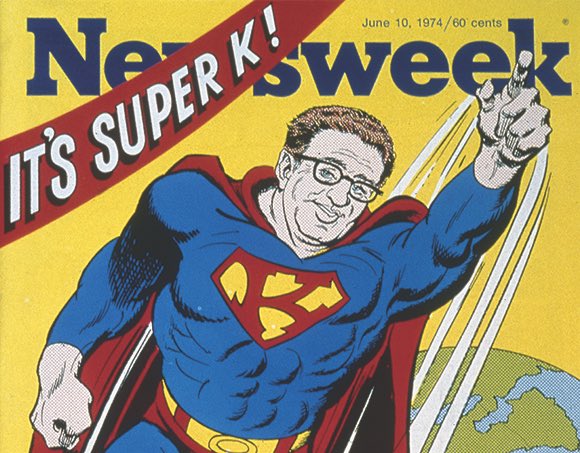

(Pisar had encountered Nixon’s national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, while at Harvard.) Blinken's late stepfather was Samuel Pisar, the longtime lawyer and confidant of Robert Maxwell - a Mossad agent and father of Ghislaine Maxwell.

Pisar was perhaps the last person to

Pisar was perhaps the last person to

speak to Robert Maxwell before he died after falling off his yacht. FOR PART OF HIS CAREER, Albert Gore Sr., received two paychecks: one from the taxpayers and another from Hammer. Hammer, who raised prize bulls, met the elder Gore at a Tennessee cattle auction in the 1940s. He

put Gore, who was then a member of the House, on the payroll of his New Jersey cattle business. Thus began a cozy relationship between the two men that would last until Hammer’s death in 1990.

Hammer personified the worst excesses of both capitalism and Communism. In his

Hammer personified the worst excesses of both capitalism and Communism. In his

biography of Hammer (Dossier: The Secret History of Armand Hammer), Edward Jay Epstein notes that Hammer built a pencil factory outside Moscow in 1926 and returned to the United States soon after to launder funds for the Communist Party. In the 1930s, Hammer marketed something

he called the “Romanoff Treasure,” a collection of fake Russian art that he passed off as genuine. In April 1968, Senator Gore stood by Hammer’s side when the industrialist officially opened his Libyan oil fields. Occidental was not a player in world crude-oil markets until

Hammer bribed King Idris and some of his officials to gain a concession to the huge reserves there. Two years after Gore left the Senate, Hammer placed him on Occidental’s board of directors, where he earned a much higher salary than he had as a U.S. senator.

Gore and Chernomyrdin signed a 20-year, $12 billion deal under which Russia would ship its weapons-grade uranium to the United States. The U.S. Enrichment Corp. (then government-owned) would buy the highly enriched uranium, process it into lower grade, reactor-friendly uranium

and sell it to nuclear power plants in the United States. The cash-starved Russian government would get much-needed dollars to pay its nuclear scientists, those scientists would not be tempted to offer their services around the world, and nuclear material would be under the

protection of the United States.

IT LOOKED GOOD ON PAPER, but it didn’t work out that way. In 1996, Congress passed a bill to privatize the U.S. Enrichment Corp., a move that threatened the Gore-Chernomyrdin agreement, though one that in fact would ultimately benefit Gore.

IT LOOKED GOOD ON PAPER, but it didn’t work out that way. In 1996, Congress passed a bill to privatize the U.S. Enrichment Corp., a move that threatened the Gore-Chernomyrdin agreement, though one that in fact would ultimately benefit Gore.

Foreign policy experts including Thomas Neff, a senior researcher for the Center for International Studies at the Massachusetts Institute for Technology, who conceived of the uranium agreement warned that privatization threatened the deal. A privatized, profit-seeking U.S.

Enrichment Corp., would pay Russia far less cash for its uranium than the amount Gore and Chernomyrdin had originally agreed on. Gore, as the broker of the deal, was in a perfect position to lobby against the privatization scheme. He didn’t. Instead, the Clinton-Gore

administration wholeheartedly supported privatization of USEC as part of its efforts to “reinvent government.”

USEC’s board of directors, led by William Rainer, a large donor to the Presidential Inaugural Committee in 1993, had decided to consider two options: Sell the company

USEC’s board of directors, led by William Rainer, a large donor to the Presidential Inaugural Committee in 1993, had decided to consider two options: Sell the company

to a behemoth like Lockheed Martin Corp., or go it alone with an initial public offering. AS NEFF AND OTHER EXPERTS had predicted, however, the deal soon began to unravel. Later in 1998 USEC announced that it had received shipments of uranium from the U.S. Department of Energy.

The sudden glut caused the worldwide price of uranium to plummet, and the Russians suddenly stood to receive less money than they had been promised. Yeltsin’s government cried foul and threatened to sell its nuclear material to other countries, including Iran. The White House

scrambled to come up with the money the Russians demanded, and managed to quietly slip an extra $325 million for the Russians a taxpayer-financed bailout into an omnibus appropriations bill before Congress.

Neff, the architect of the plan to ship Russia’s weapons-grade uranium to USEC for reprocessing, estimates that it will cost taxpayers $140 million a year for 15 years to continue purchasing the Russian nuclear material, for a total cost of $2.1 billion or $200 million more than

the sale of USEC brought in. Gore’s “reinvention” of USEC made a lot of money for some of his most reliable political patrons. It also endangered nuclear arms control and left in private hands the management of facilities that are contaminated with deadly substances.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh