A 🧵 about American politics, political history, and historical memory—and a text so often found at the crossroads of all three: The Federalist Papers.

Teaser: Read on to find out how a 1961 book cover used an 1848 painting to depict—and distort—1787/88.

Teaser: Read on to find out how a 1961 book cover used an 1848 painting to depict—and distort—1787/88.

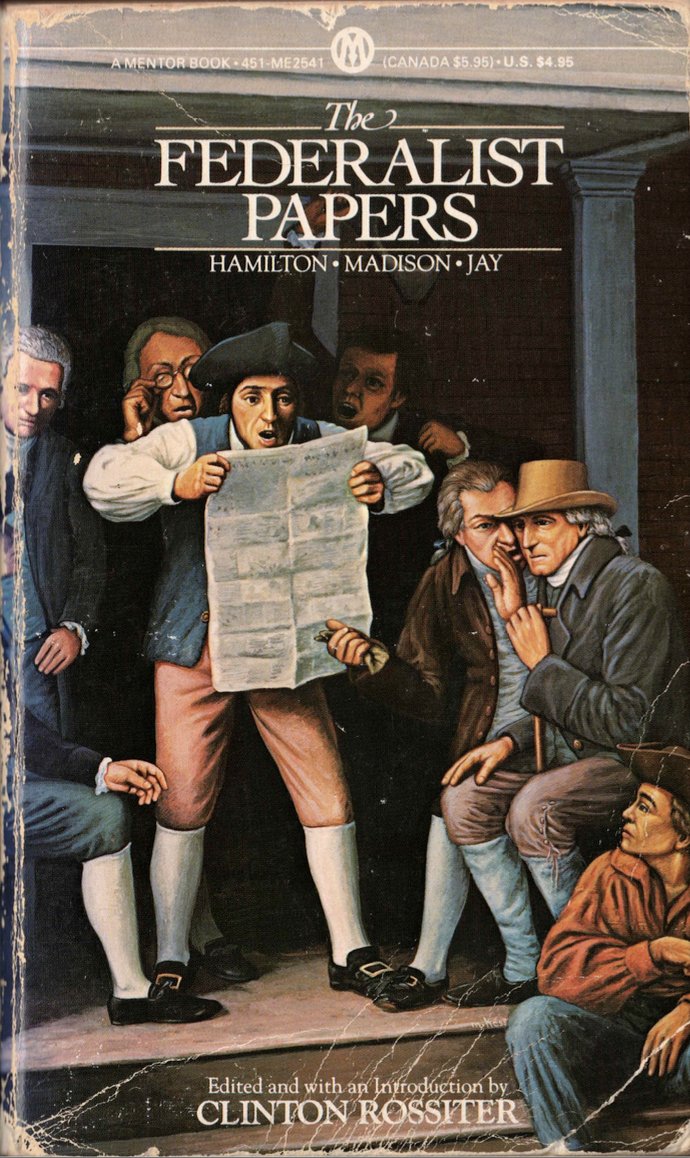

To start, here’s the cover of the 1961 edition of The Federalist Papers (TFP), edited by Clinton Rossiter and published by Mentor Books. Those who teach TFP have probably seen this image…a lot. It’s one of the most ubiquitous copies of the text.

The cover image seems straight-forward: Citizens are reading news about the proposed constitution! And this makes sense. After all, the essays we now call The Federalist Papers were initially printed in and read from newspapers.

The people seem shocked, enthused, and enthralled by what they are reading and hearing. That too makes sense—it’s not every day you (maybe) get a new constitution!

But it’s also an odd picture. For one thing, it wasn’t original. It was based on this 1848 painting by Richard Caton Woodvile, "War News from Mexico." Woodville’s painting is *much* more detailed and *much* more interesting than the version that appears on the cover of TFP. Look!

As the title suggests, Woodville’s panting depicts the publication & reception of news about the Mexican-American War. In the treaty that concluded the war, Mexico ceded to the United States the territory that would eventually become all or part of TX, NM, CO, AZ, UT, NV, and CA.

That expansion would re-pose the central question of the era: Would the states-to-be-added be slave states or free states? Woodville’s paining depicts the uncertainty & division of opinion about the war. Perhaps that’s why the “American Hotel” sign at the top is cut in half.

Was the news good or bad? Who knows! The painting illustrates layers of interpretation: while some read the newspaper, others listen to what is being read, and still others have that heard message translated for them. Some are shocked, others happy, yet others unsure.

Finally, and typical of genre paintings, there’s the social hierarchy. The central characters, white men all, are framed by the portico. At the margins are three other figures: an old woman looking out from inside the building, & a Black man with what appears to be his child.

Just as the woman is placed inside the building and at the edge of the painting, the Black figures are placed lower than—literally a step below—the white figures.

So much more could be said about the detail and meaning of Woodville’s painting, but the important point is this: The version used for the cover of The Federalist Papers removes nearly all of that! And it’s not just cropped; it’s altered and distorted.

Some of this was presumably a consequence of the format of the book cover. Even so, the central figures in both versions are virtually identical. So I think the differences are important and instructive.

Perhaps most striking, the figure in the bottom right is not obviously Black! He’s lightened, made more respectable & less socially distant from the main figures. And, of course, there is no child. The centrality of slavery to the original painting has been obscured.

(Maybe this is just me, but after years of reading and teaching from this book, it took seeing Woodville’s painting to realize that that man might actually be Black.)

The only woman in Woodville’s painting is cut out entirely. So while Woodville *depicted* the social/legal/political marginalization and exclusion of the time, the cover of TFP enacts or performs that marginalization and exclusion.

Comparing the two images, it seems to me that nearly all of the important detail of the original has been removed: The layers of political meaning are compressed & flattened, the social hierarchy is absent, & the story it tells is simultaneously abstracted & homogenized.

Wrenched from its original context & shorn of its detail & complexity, the image tells not just a different story but a less true & less meaningful one. And that, it seems to me, is quite relevant to current discussions about how & what we teach about American politics & history.

Thanks to @RrjohnR who (in response to a tweet by @UnlawfulEntries) flagged the use of Woodville’s painting for the cover. For more about the painting, check out this *incredible* article and video put together by @Smarthistory. smarthistory.org/richard-caton-…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh