It's incredibly thrilling to have this paper out at last! 🎉

"Spread of a #SARSCoV2 variant through Europe in the summer of 2020"

(aka The Tale of Europe, Summer Travel, & EU1)

But why should we care about summer 2020 now? Let's take a look...

nature.com/articles/s4158…

1/24

"Spread of a #SARSCoV2 variant through Europe in the summer of 2020"

(aka The Tale of Europe, Summer Travel, & EU1)

But why should we care about summer 2020 now? Let's take a look...

nature.com/articles/s4158…

1/24

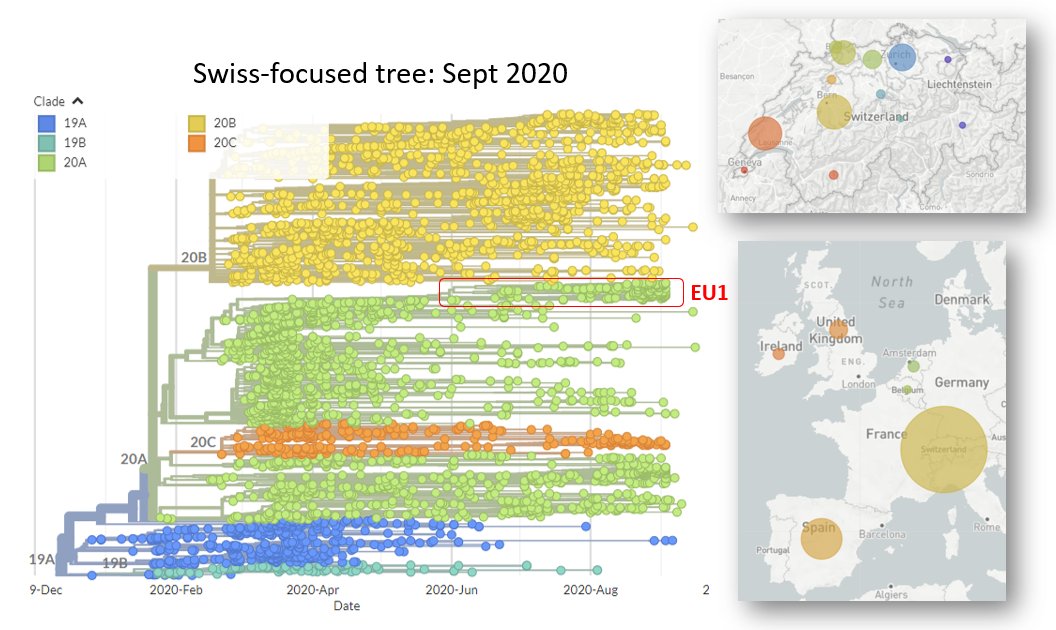

Last Sept, while looking for #SARSCoV2 sequences that could help us understand transmission across #Switzerland, I noticed a cluster that was present not just across Switzerland, but also the UK & Spain. This is the cluster that eventually came to be known as 20E (EU1).

2/24

2/24

EU1 had a mutation at position 222 in spike - this caught my eye.

From mid-summer 2020, EU1 (orange) expanded across Europe - becoming the most prevalent variant in most of Western Europe, & accounting for >30% of sequences in Europe by the end of 2020.

3/24

From mid-summer 2020, EU1 (orange) expanded across Europe - becoming the most prevalent variant in most of Western Europe, & accounting for >30% of sequences in Europe by the end of 2020.

3/24

We can see how EU1 rose over summer 2020 by looking at % of sequences each week that fell into EU1.

From initially expanding in Spain 🇪🇸, it quickly started being detected in other countries soon after EU borders opened in mid-June. ✈️🔛

4/24

From initially expanding in Spain 🇪🇸, it quickly started being detected in other countries soon after EU borders opened in mid-June. ✈️🔛

4/24

We see a general pattern of a rise, then a plateau in proportion, & a wide variation in how much EU1 dominated in different countries: in Spain, Ireland, & UK it was >60% sequences - in Norway & France it was <=20% by end of 2020, with other countries in between.

5/24

5/24

We were able to confirm Spain as the origin of expansion through phylogenetics - a collapsed phylogeny of seqs up to 30 Sept shows countries with shared genotypes as pie charts.

The earliest diversity is found in Spain (red) & shared with many other countries.

6/24

The earliest diversity is found in Spain (red) & shared with many other countries.

6/24

My initial concern was that EU1 was what we were all fearing in 2020: a more transmissible variant. 😱

But laboratory work showed no difference in antibody binding (pic 1) or pseudoviral titers (pic 2).

So how did it spread so successfully?🤔

7/24

But laboratory work showed no difference in antibody binding (pic 1) or pseudoviral titers (pic 2).

So how did it spread so successfully?🤔

7/24

The summer of 2020 followed on from one of the hardest springs in memory.

On heels of lockdowns, economic hurt, hospitalizations & death, it was defined by hopeful restriction loosening & a longing to regain normality.

Could travel have played a role in EU1's success? 🧳🛫

8/24

On heels of lockdowns, economic hurt, hospitalizations & death, it was defined by hopeful restriction loosening & a longing to regain normality.

Could travel have played a role in EU1's success? 🧳🛫

8/24

We were able to look closely at #SARSCoV2 cases across Europe over the summer (pic 1), including cases by Spanish province.

In addition, we looked at travel (pic 2). We used📱roaming data from across Europe to see when & where in Spain visitors went.

9/24

In addition, we looked at travel (pic 2). We used📱roaming data from across Europe to see when & where in Spain visitors went.

9/24

By combining the case numbers per province over time😷, with the location data 🗺️, plus info on their home country epidemic, we knew (generally) where people came from, where they went in Spain, & when.

We could use this in a simple model to predict how EU1 spread:🔀

10/24

We could use this in a simple model to predict how EU1 spread:🔀

10/24

While this matches the dynamics fairly well, our model was underestimating the proportion of EU1 cases.

In some countries we did well (France), in others off by 2-4x (pic 1). But in others we were off between 7-11x (pic 2)!

What wasn't our model capturing? 🤔

11/24

In some countries we did well (France), in others off by 2-4x (pic 1). But in others we were off between 7-11x (pic 2)!

What wasn't our model capturing? 🤔

11/24

When we compared our estimated travel-related cases with those reported by the German & Swiss govts (only German shown), we confirmed that our model was underestimating the likelihood of bringing EU1 home.

Our model really was simple: there's plenty it doesn't capture...

12/24

Our model really was simple: there's plenty it doesn't capture...

12/24

For example: people don't go to the same places in Spain on holiday! French visitors stay north 🌄, whereas UK holidaymakers head south & to islands 🏖️ (pic 1).

Countries have similar & differing travel patterns (pic 2).

13/24

Countries have similar & differing travel patterns (pic 2).

13/24

See the paper for full discussion, but what our model's underestimation suggests is that travel related activities are associated with more cases than expected:

Demographics, behaviour, & variation in incidence (city vs province-level) likely play a role.

🚶🏻♀️🍽️🏊🏻♀️🕺🏻💃🏻👨👧

14/24

Demographics, behaviour, & variation in incidence (city vs province-level) likely play a role.

🚶🏻♀️🍽️🏊🏻♀️🕺🏻💃🏻👨👧

14/24

But this was last summer... & EU1 isn't even more transmissible. So why should we care about it now?! 🤨

As we head once again into summer & the balance of travel & transmission, while hearing about new variants -

I think EU1 can still tell us some very important things!

15/24

As we head once again into summer & the balance of travel & transmission, while hearing about new variants -

I think EU1 can still tell us some very important things!

15/24

EU1 underscores the potential impact of travel.

Last summer in Europe travel persisted as cases rose in Spain. There was essentially no testing, & quarantine may not have worked as well as we wished. Test&Trace didn't stop transmission chains.

16/24

ft.com/content/d214ef…

Last summer in Europe travel persisted as cases rose in Spain. There was essentially no testing, & quarantine may not have worked as well as we wished. Test&Trace didn't stop transmission chains.

16/24

ft.com/content/d214ef…

Differing travel volumes, locations & behaviours likely played a role.

Similarly, when we look at the spread of the Delta variant now in the UK vs other European countries, closer ties to India likely meant the UK has had many more introductions.

17/24

nriol.com/indiandiaspora…

Similarly, when we look at the spread of the Delta variant now in the UK vs other European countries, closer ties to India likely meant the UK has had many more introductions.

17/24

nriol.com/indiandiaspora…

EU1 also highlights that bans to just one country probably aren't enough on their own:

By end-Sept 2020, there was more EU1 in Europe outside of Spain than inside of Spain.

It wasn't about Spain anymore: other Europe countries were transmitting after failing to control it.

18/24

By end-Sept 2020, there was more EU1 in Europe outside of Spain than inside of Spain.

It wasn't about Spain anymore: other Europe countries were transmitting after failing to control it.

18/24

But perhaps most importantly of all, EU1 shows us that not all rising frequencies are due to viral change.

EU1 rose in frequency when cases were rising, & had a spike mutation - an alarming combination. But it was not a variant of concern - rather a travel opportunist.

19/24

EU1 rose in frequency when cases were rising, & had a spike mutation - an alarming combination. But it was not a variant of concern - rather a travel opportunist.

19/24

As we identify new variants, the critical question is to what degree viral changes are influencing transmission & cases, & how much might be changes in restrictions, behaviour, introductions & more.

EU1 reminds us how important it is not to underestimate the latter!

20/24

EU1 reminds us how important it is not to underestimate the latter!

20/24

EU1:

- Underscores the potential impact of travel particularly when incidence differs between countries 🛫🧳

- Highlights what didn't work last summer 😷🏖️

- Reminds us that not all rising frequencies are due to viral change! 📈🦠

21/24

- Underscores the potential impact of travel particularly when incidence differs between countries 🛫🧳

- Highlights what didn't work last summer 😷🏖️

- Reminds us that not all rising frequencies are due to viral change! 📈🦠

21/24

This work thanks to:👏🏻

@MoiraZuber @SarahNadeau19 Tim Vaughan @khdcrawford @C_Althaus Martina Reichmuth, John Bowen @coronalexington Davide Corti @VirBiotech @jbloom_lab @veeslerlab David Mateo @kidodynamics Alberto Hernando @icoes @fgonzalef @TanjaStadler_CH @richardneher

22/24

@MoiraZuber @SarahNadeau19 Tim Vaughan @khdcrawford @C_Althaus Martina Reichmuth, John Bowen @coronalexington Davide Corti @VirBiotech @jbloom_lab @veeslerlab David Mateo @kidodynamics Alberto Hernando @icoes @fgonzalef @TanjaStadler_CH @richardneher

22/24

I'm absolutely honoured to have worked with so many amazing people on the EU1 story.

They not only made it possible through collaboration & data sharing - they made it better & made it a true pleasure to work on. 🙏🏻

In this pandemic, the only way forward is together. 👩🏻🤝👨🏾

23/24

They not only made it possible through collaboration & data sharing - they made it better & made it a true pleasure to work on. 🙏🏻

In this pandemic, the only way forward is together. 👩🏻🤝👨🏾

23/24

A short informal 'press release' covering the new paper can be found here:

docs.google.com/document/d/1b0…

24/24

docs.google.com/document/d/1b0…

24/24

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh