Hey linguists: does anyone know of a use before 1937 of "complementary distribution" (the term, not the concept) referring to allophones and phonemes? The earliest use I've found is in "The Origin of Aztec TL" by Whorf (1937). Wondering if he was first to use it that way.

The term existed infrequently in the natural sciences before it was used in linguistics, but only became frequent around the same time that Whorf coined "allophone" (see graphs).

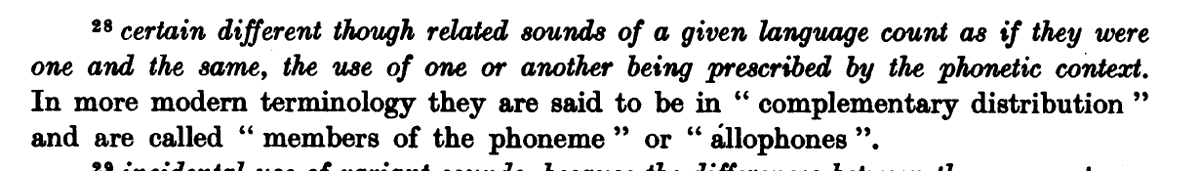

The idea of complementary distribution was around, just not that name for it. Whorf coined "allophone" ~1934, though first known use in print is Trager and Bloch (1941). Jones (1957) documents the origins of "phoneme" and "allophone", and has this footnote about his 1917 work.

The first English use of "phoneme" in the modern sense was by Jones (1917), borrowed from the Russian "fonema". The Russian term was coined in the 1870s by a student named Kruszewski, but (his teacher) Baudouin de Courtenay first developed a theory of phonemes starting ~1868.

(Jones also credits a couple of others with independently coming up with an idea similar to phonemes. Sweet in the 1870s with his “broad” vs “narrow” transcription, and probably also Passy around the same time, which went on to influenced the first IPA formulation.)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh