I think it’s important to explain why this take by @Dominic2306 is wrong (particularly as the thread goes on to call for - unspecified - JR reforms, on the basis that this shows why JR is damaging to good government). (Long thread)

https://twitter.com/dominic2306/status/1402575655632527363

First, when reading his criticisms of the detailed procurement rules, remember that the judge actually found that (apart from the apparent bias issue) the government complied with those rules and was entitled to use the emergency procedures.

(Judgment here: see grounds 1 and 2 - paras 71-131.) drive.google.com/file/d/1zf_3NX…

There is lots of room for improvement in the detailed rules, but the case - since it upheld the government on these points - does not really assist the complaint that they don’t allow enough room for manoeuvre in an emergency.

But what about ground 3: apparent bias?

Let’s start with a basic point. The rule against apparent bias is critical to fair and competent administrative (and judicial) decision making.

That’s because actual bias is so hard to establish (you can’t see into the decision-maker’s mind, and she will often genuinely believe she was unbiased while being subconsciously biased).

But the danger of bias infecting decision-making and making it worse - bad government- is enormous: and the perception of bias is deeply corrosive of public confidence in fair and competent decision-making (on which effective government in an open society ultimately depends).

The rule against apparent bias is therefore not an optional extra: it is actually essential to good - and legitimate - government.

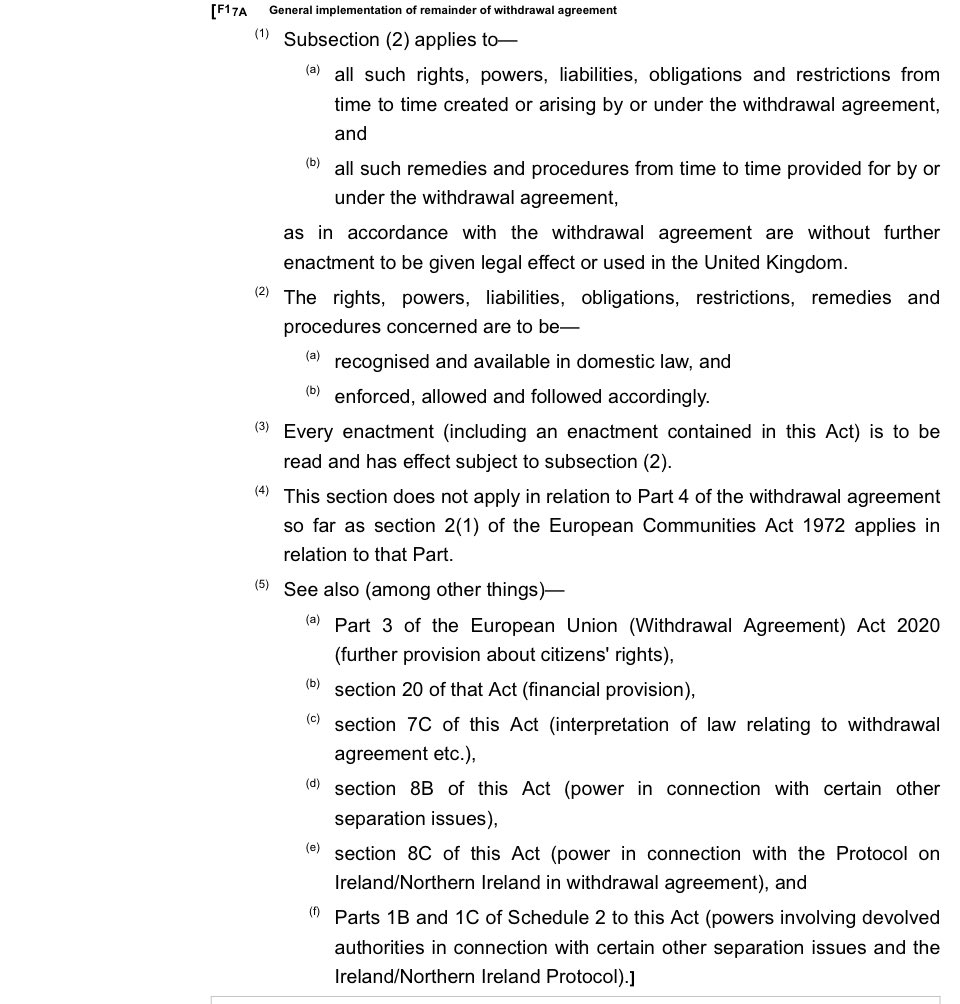

What about the complaint that it’s all about paper-trails and box-ticking? Well, have a read of paras 132-169.

First point: the court accepts that Cummings was entitled to be involved in the decision notwithstanding his knowledge of and friendships with the potential contractors: para 146.

That is realism: in a small world people will know each other, have views about each other, and sometimes be friends. But decisions about that small world need to be taken, often by people from it.

Now, the “box-ticking” complaint. It’s true that the Court did consider that there should have been a clear record of the objective criteria used: para 147. And para 153 refers to the need to be able to evidence that those criteria were applied.

But that isn’t the reason the government lost. The reason the government lost is at 157-158: it’s that (a) the government’s advanced reasons for appointing PF at speed didn’t stand up to scrutiny and (b) those weren’t actually the reasons used at the time.

The points made by the court boil down to the points that no one considered what the right criteria were; and no one considered an alternative. Those aren’t points about recording or box-ticking: they are points about substance: about whether the decision was a good one.

But what about the “extreme urgency” point? The problem is that extreme urgency doesn’t justify not spending a moment to identify what you actually want the contractor to do and who is likely to be good at doing it: that is a basic element of good procurement decision-making.

(And the key complaint isn’t that those criteria weren’t recorded: it’s that they weren’t identified at all.)

As for the “no time to identify an alternative” point, the court again doesn’t rely on an absence of records but notes that the possibility wasn’t in fact considered at all (even though PF would have to be brought up to speed - see para 162).

The complaint about box-ticking is therefore wrong-headed: the problem was with the substance of the decision, not record-keeping.

Not identifying what you need from suppliers and not thinking about alternatives is just not good procurement decision-making.

And bad decision-making is bad whether you are in an emergency or not (indeed, in an emergency with lives at stake, getting it right is more, not less, important).

The combination the accepted friendships/connections with the finding of (in essence) poor decision-making led to the finding of apparent bias. It is not about record-keeping and paper trails.

Nor does the judgment stop fast decision-making in an emergency. If you think about the right things that go into a good decision (as you shld) you will be fine. (Recording those things will help - not least because recording things often clarifies thought - but isn’t essential).

Final thought. It’s interesting (tweet 81) that Cummings takes credit for starting the “JR reform” process. Rather what many had suspected.

It is however entirely unclear to me how any of the proposed changes would have affected the present case (though many of them are highly objectionable on other grounds).

PS “Potemkin” meetings - like Potemkin anything - don’t work. In the end, public law is about reality, not form. It is thinking about the right things in the right way (the way the law and good administration require) that matters: doing things for show doesn’t (& shldn’t) work.

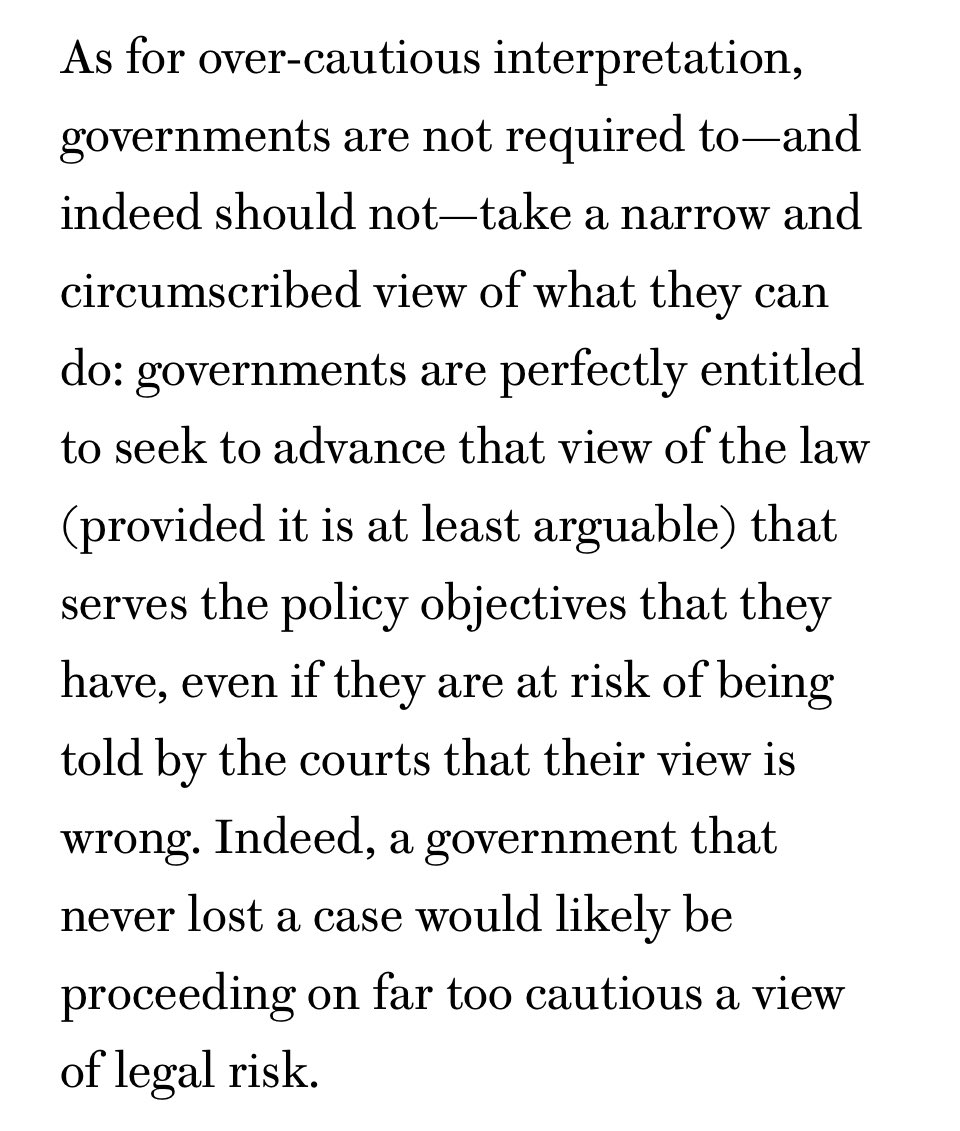

PPS: I have some sympathy with what Cummings says about a tendency in Whitehall to use a risk of JR as an excuse for inaction. See from a short blog of mine in today’s Prospect: prospectmagazine.co.uk/politics/law-l…

I (and I think most barristers who have frequently represented the govt) have come across cases where the risk of JR was being taken as a reason not to do something when, actually, there was a perfectly good legal case for it which could be confidently and properly advanced.

It also isn’t helpful that government defeats are often seized on as a humiliation for the minister concerned. They shouldn’t be*: the law is sometimes unclear, and judgments on questions of fairness or rationality can properly differ.

The sound of government losing some JRs is the sound of a system working.

(*A JR may reveal conduct that *is* a resigning matter: but the mere fact of losing a JR shouldn’t be.)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh