A series of points on the Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol.

1. It sets out binding obligations under international law - as an integral part of the Withdrawal Agreement.

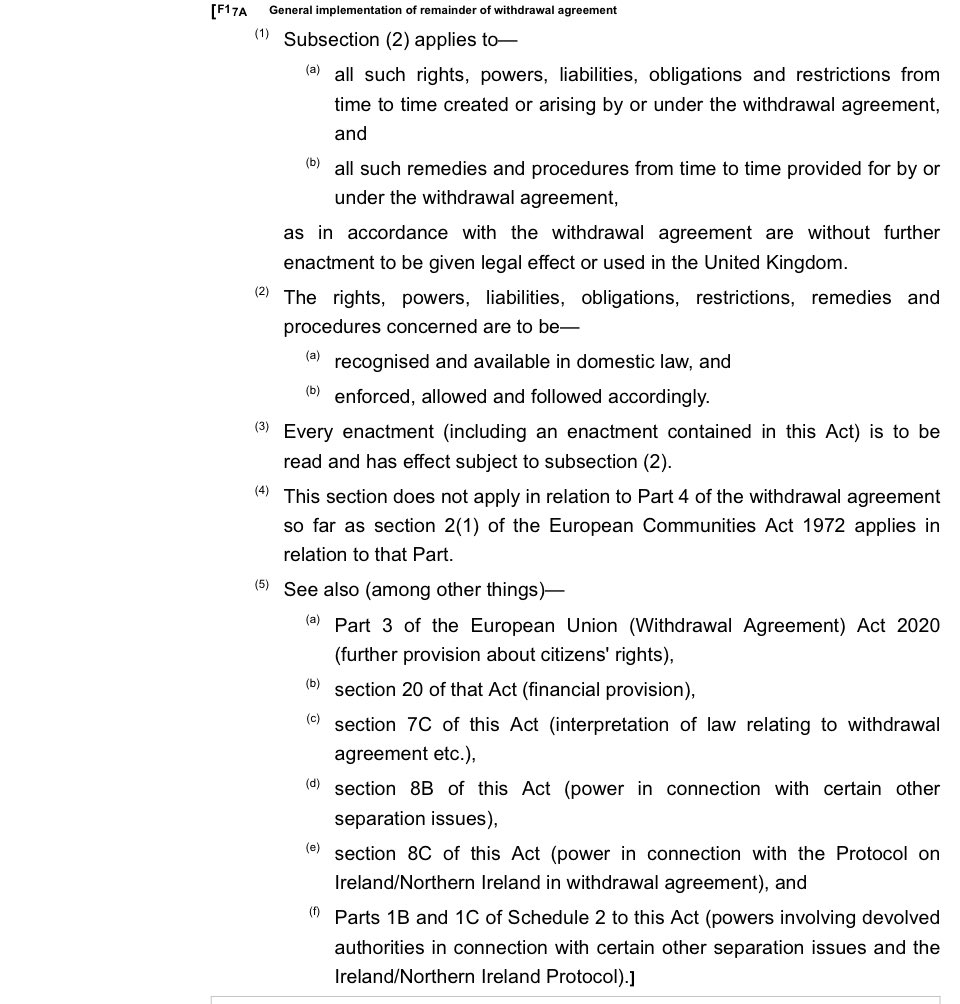

2. It is also incorporated into U.K. law (s.7A of the EU Withdrawal Agreement). It binds the U.K. government as a matter of domestic law (subject to legislation clearly overriding it, which would be unlikely to clear the House of Lords).

3. No, Secretary of State: it is not a “policy document”: it is U.K. and international law.

https://twitter.com/adampayne26/status/1405175076799008773

4. No, Secretary of State: the requirements for GB-NI checks and controls are set out in the Protocol with legal clarity (albeit in a way that is designed to distract a lazy reader - but no one in the current govt falls under that head).

https://twitter.com/adampayne26/status/1405175076799008773

5. The Protocol provides that, with limited exceptions to be agreed by the EU, EU law on the regulation of goods, VAT, state aid (some wrinkles there), and customs applies in full to NI.

6. That means that if GB chooses, in those fields, to diverge from the EU, GB/NI divergence grows too. Those who claim to value the Union need to hold onto that fact, in making choices for GB.

7. NI didn’t consent to the Protocol: though it can get rid of it in 2024.

8. Those complaining about that fact need to remember that NI didn’t consent to Brexit either. But it happened.

9. It is undemocratic - and possibly a breach of A3P1 of the ECHR - that NI is now subject to tax and regulatory laws in which it has no say.

10. Any claim that the Protocol is a technical trade matter and not of constitutional significance fails to grapple with the point that constitutions usually have quite a lot to say about internal trade, and also on who determines tax and regulation.

11. But the fact that the Protocol is constitutional doesn’t necessarily mean that it represents a change in NI’s status as part of the U.K. to which the people of NI should consent, under the Good Friday Agreement.

12. The democratic issue was obvious to anyone who read the Protocol in 2019. The term “shameless effrontery” is apt to cover those who now complain about it, but in 2019 voted for it, went along with it, said it was a “great deal”, or said no one needed to scrutinise it.

13. The Protocol compromises the sovereignty of the U.K. It also compromises the sovereignty of the EU27. That’s what treaties are: compromises of sovereignty.

14. Proposals that the EU drop its standards, relax its controls, or treat Ireland differently from other Member States are demands that EU27 States compromise their sovereignty. See 13 above.

15. The Protocol means that NI producers of goods can sell throughout the EU without trade and customs barriers. They do not face the huge trade obstacles now facing GB exporters to the EU. And NI suppliers can also sell freely to GB. There are some advantages, there.

16. The Protocol is the answer to the tragic problem: a problem to which there is and can be no satisfactory answer. It is easy to criticise it. But the criticism is interesting only if it has (non- 🦄) solutions attached.

17. Finding solutions to practical problems involves compromise and some acceptance of risk on the EU side. The Protocol requires the EU to address such ameliorations constructively.

18. But getting the EU to trust the current government, and to accept risk, has been made harder by the current government’s persistent misrepresentation of what the NIP says, of its binding nature, and by its threats to breach it.

19. In the medium to long run, the democratic deficiency - the lack of say by the people of NI in many of rules and taxes that apply to them - is going to be a problem. Wise heads will be thinking about how to deal with that: the answer isn’t going to be simple (it never is).

PS worth noting the two errors in this tweet (what was agreed on customs - where the tweet is just wrong as brilliantly explained here eulawanalysis.blogspot.com/2020/03/the-pr… - and the “contrary to the GFA” point, as to which see 11 above.

https://twitter.com/bencorke/status/1405514550242390016

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh