It's time to talk about time, or perhaps rather the taming of time, or however you say it. It's time to talk about calendars.

There are several independent, or nearly, parts of a calendar: 7-day weeks (whatever you call the days), months, and how many years since X.

1/x ~tac

There are several independent, or nearly, parts of a calendar: 7-day weeks (whatever you call the days), months, and how many years since X.

1/x ~tac

The three big questions shaping any calendar are:

(1) are months based on the moon (lunar), or a fixed numbers of days?

(2) is the year based on the sun (solar), or a fixed number of months?

(3) do they vary?

2/x ~tac

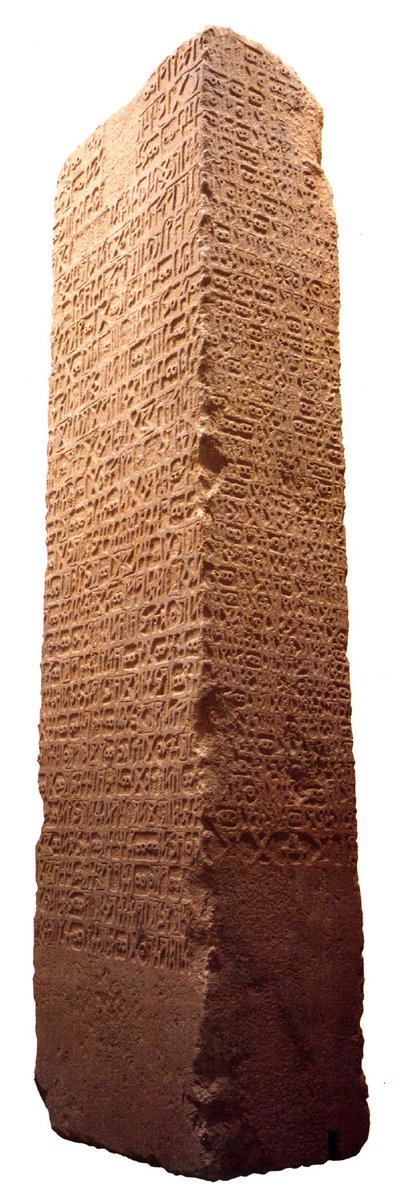

Pic by Baykar Sepoyan, CC BY-SA 4.0, commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?cu…

(1) are months based on the moon (lunar), or a fixed numbers of days?

(2) is the year based on the sun (solar), or a fixed number of months?

(3) do they vary?

2/x ~tac

Pic by Baykar Sepoyan, CC BY-SA 4.0, commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?cu…

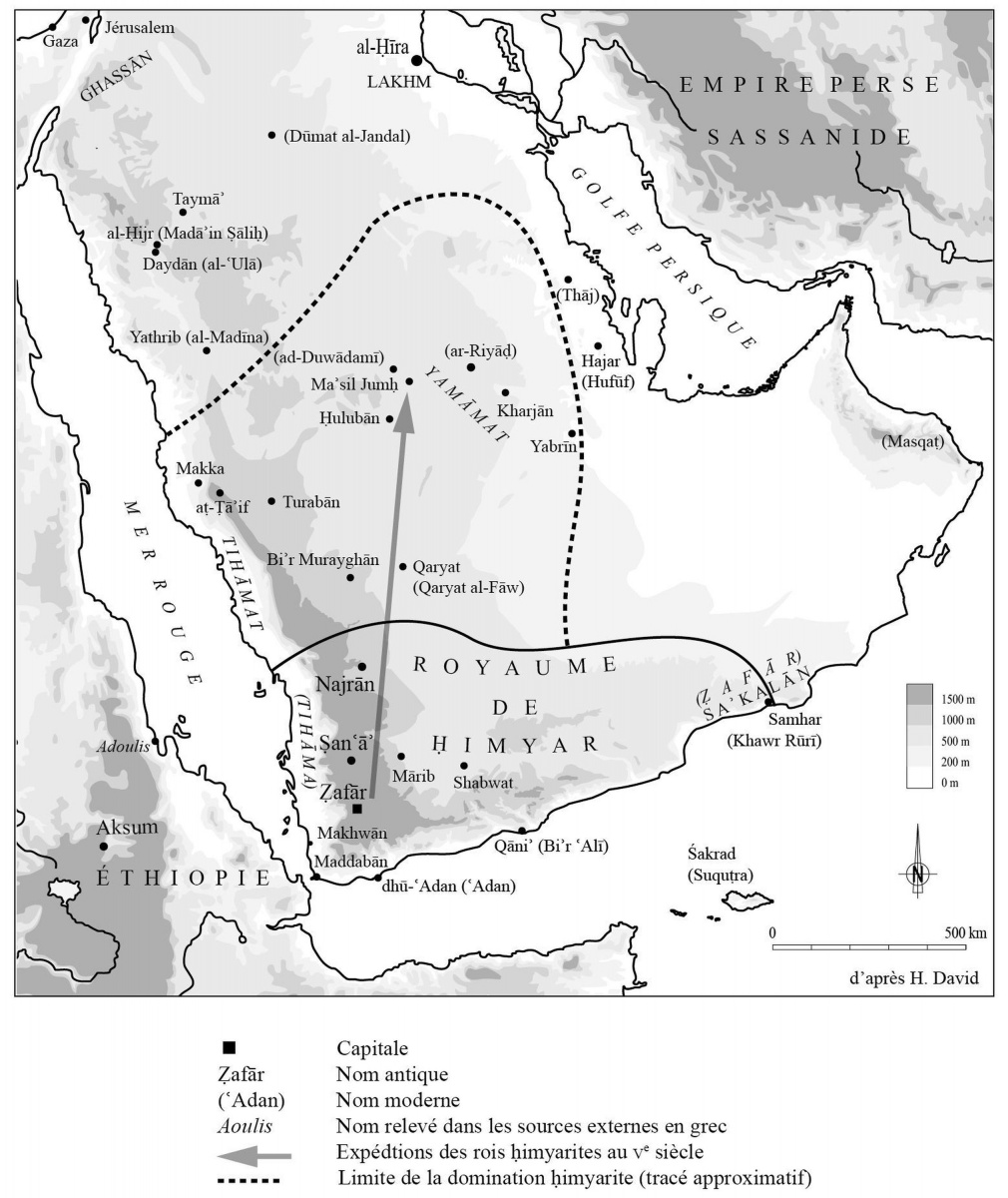

Hijri (Islamic):

lunar months, 12/year

Jewish:

lunar months, 12-13/year

Julian, Seleucid, Greek Anno Mundi:

fixed months, 12/year, leap day every 4 years

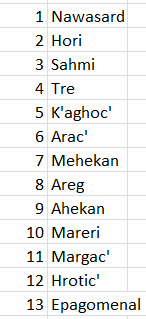

Armenian:

Julian w/o leap days

Jalali:

zodiac months, 12/year

But they all agreed which day was Saturday!

3/x `tac

lunar months, 12/year

Jewish:

lunar months, 12-13/year

Julian, Seleucid, Greek Anno Mundi:

fixed months, 12/year, leap day every 4 years

Armenian:

Julian w/o leap days

Jalali:

zodiac months, 12/year

But they all agreed which day was Saturday!

3/x `tac

Question #4 is: when was year 1?

Hijri calendar: (lunar) years since Muhammad's Hijra

Jewish & Greek Anno Mundi: (solar) years since Creation (but different numbers, neither agrees with Usher)

Julian: since Rome

Seleucid: since Seleucus Nicator

Armenian: since 552 CE?

4/x ~tac

Hijri calendar: (lunar) years since Muhammad's Hijra

Jewish & Greek Anno Mundi: (solar) years since Creation (but different numbers, neither agrees with Usher)

Julian: since Rome

Seleucid: since Seleucus Nicator

Armenian: since 552 CE?

4/x ~tac

(Twitter refused to upload my image of Usher. That's a harsh comment on his looks.)

There's also a #Zoroastrian calendar and Yazdegerd Era, about which I know too little.

And I forgot Armenians have 12 months of 30 days followed by 5 "epagomenal days" to get 365.

5/x ~tac

There's also a #Zoroastrian calendar and Yazdegerd Era, about which I know too little.

And I forgot Armenians have 12 months of 30 days followed by 5 "epagomenal days" to get 365.

5/x ~tac

When was New Year's? Spring equinox in Persia, October 1 in the Seleucid era, etc...

And because the years were different lengths, they did not stay in sync. So conversion is messy! (Also true in general.)

Different year lengths led to different simultaneous uses.

6/x ~tac

And because the years were different lengths, they did not stay in sync. So conversion is messy! (Also true in general.)

Different year lengths led to different simultaneous uses.

6/x ~tac

When writing a petition to a ruler, you should use whatever calendar the ruler uses!

Lunar months are more convenient when you have clear skies and limited writing.

But solar years are more convenient for agricultural seasons.

And when do you expect the taxman?

7/x ~tac

Lunar months are more convenient when you have clear skies and limited writing.

But solar years are more convenient for agricultural seasons.

And when do you expect the taxman?

7/x ~tac

15th C Muslim historians al-Maqrizi and Ibn Taghribirdi still used the Coptic calendar for recording the rise and fall of the Nile, to predict years of feast or famine.

The Catholicos in Baghdad used the Hijri calendar for dealing with caliphs [h/t Luke Yarbrough].

8/x ~tac

The Catholicos in Baghdad used the Hijri calendar for dealing with caliphs [h/t Luke Yarbrough].

8/x ~tac

Calendar conversions are necessary for astronomy, so one can find details in an astronomical manual (Zij). In 15th C Samarqand, the grandson ruler Ulugh Beg, grandson of Timur Lenk, compiled one which included the "Rumi" calendar.

Not the calendar of the poet #Rumi!

9/x ~tac

Not the calendar of the poet #Rumi!

9/x ~tac

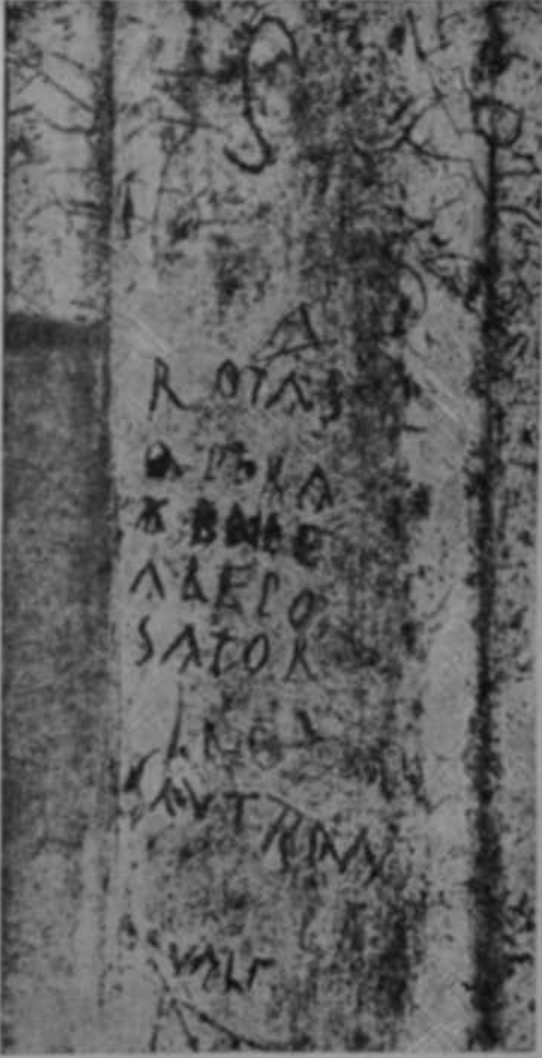

"Rumi" here means "Greek," but it's also not the Anno Mundi calendar used by the Greeks!

No, the month names make clear that this is the Seleucid era, called "Years of the Greeks" (or "of Alexander") by Syriac Christians. The "notable days" are Christian holidays.

10/x ~tac

No, the month names make clear that this is the Seleucid era, called "Years of the Greeks" (or "of Alexander") by Syriac Christians. The "notable days" are Christian holidays.

10/x ~tac

Indeed, the holidays' dates match only the Church of the East, so the astronomical manual of a Timurid prince had an unnamed "Nestorian" informant!

(Printed in London in 1650, because... why?)

Calendars are not only for the present & past; they're also for the future.

11/x ~tac

(Printed in London in 1650, because... why?)

Calendars are not only for the present & past; they're also for the future.

11/x ~tac

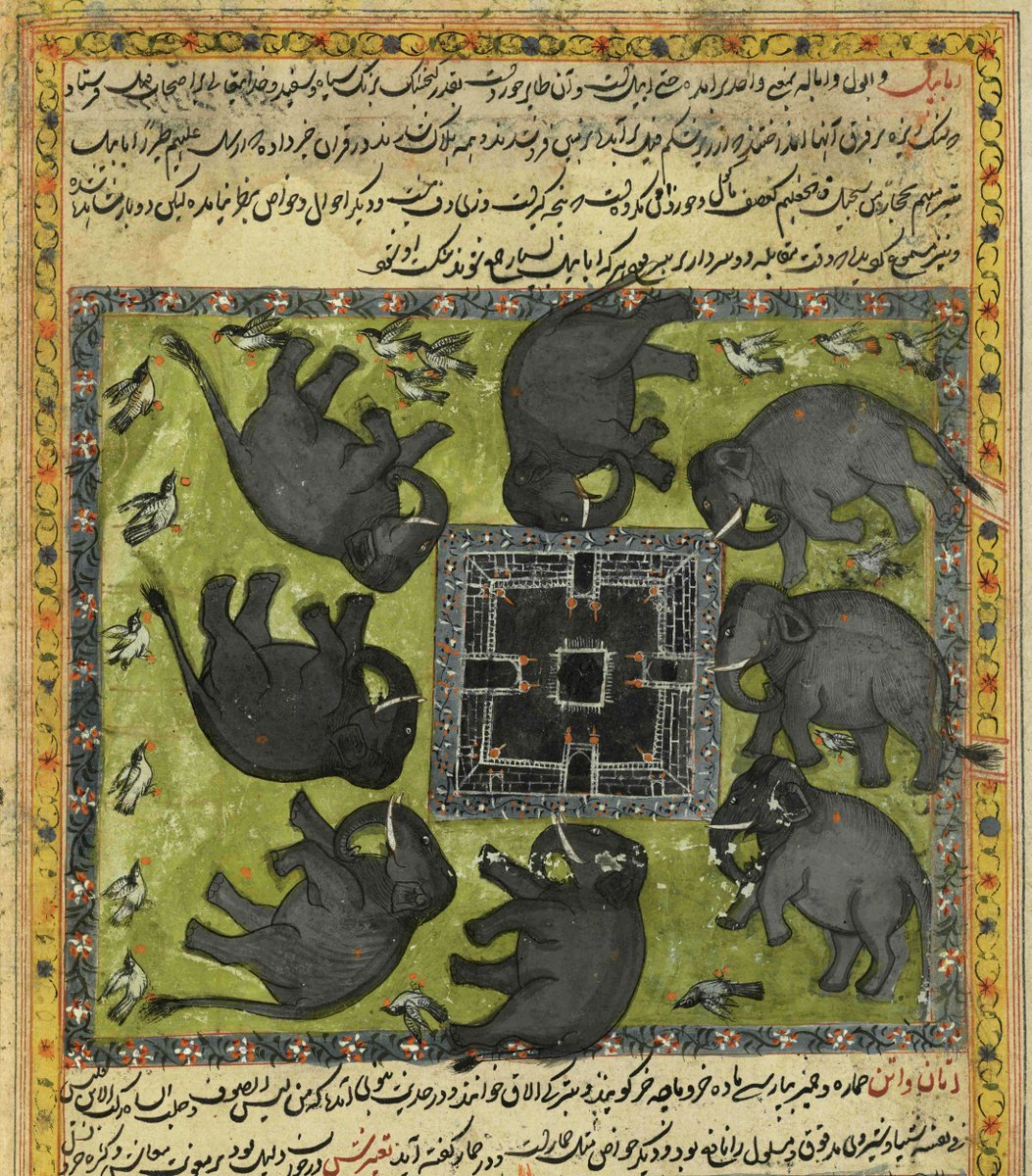

When will this world end?

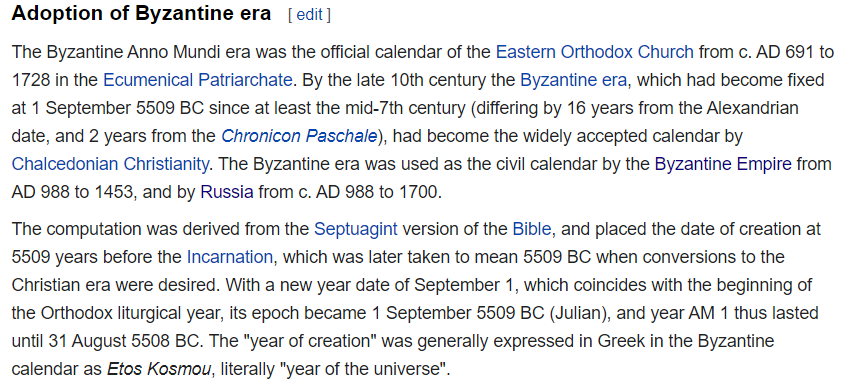

Based on their calculation of 5,509 years from Creation to Christ, no year 0, and an assumed 7,000 year duration of the world, many Greeks expected the world to end in 1492.

(It kinda did, or at least started to, for the Native Americans!)

12/x ~tac

Based on their calculation of 5,509 years from Creation to Christ, no year 0, and an assumed 7,000 year duration of the world, many Greeks expected the world to end in 1492.

(It kinda did, or at least started to, for the Native Americans!)

12/x ~tac

Shbadnaya, a 15th C priest around Mosul quoted a 7th(?) C Syriac author from the Qatar region asserting that Christianity would endure as long as Old Testament sacrifices had, which he said was 1,596 years. It's not clear whether he's counting from Christ's birth or death.

13/x

13/x

But either way (c. 1596 CE or 1629 CE), this puts Christ's return right around the year 1000 AH.

Was Hijri millennialism shared by Christians as well as Muslims? Maybe!

Calendars were diverse, usefully and meaningfully so.

Time can be tamed many different ways.

14/end ~tac

Was Hijri millennialism shared by Christians as well as Muslims? Maybe!

Calendars were diverse, usefully and meaningfully so.

Time can be tamed many different ways.

14/end ~tac

PS. Michael the Syrian also describes the Islamic belief in the Mahdi: medievalmideast.org/practice/328.h…

PPS. Descriptions of the Dajjal were shared by some Armenian Christians.

15/real end ~tac

PPS. Descriptions of the Dajjal were shared by some Armenian Christians.

15/real end ~tac

https://twitter.com/MedievalMidEast/status/1399452246933389318

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh