Today in pulp… a few musings on a new type of narrative structure that we’re seeing more and more in the 21st Century: the algorithmic story.

Don’t worry, it’s not that complex. Yet.

Don’t worry, it’s not that complex. Yet.

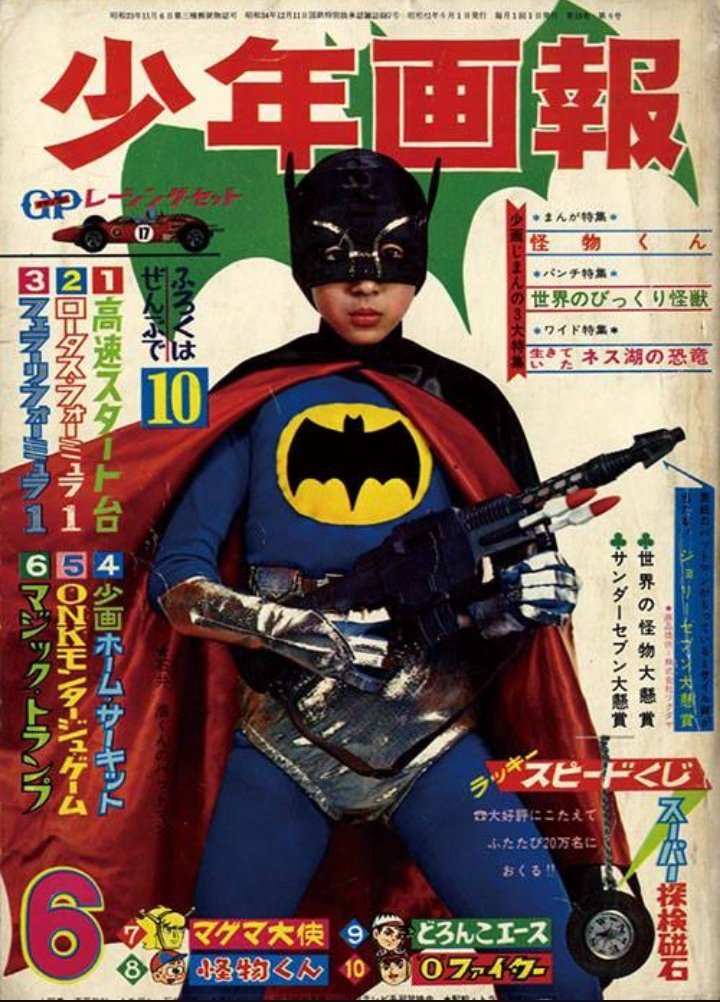

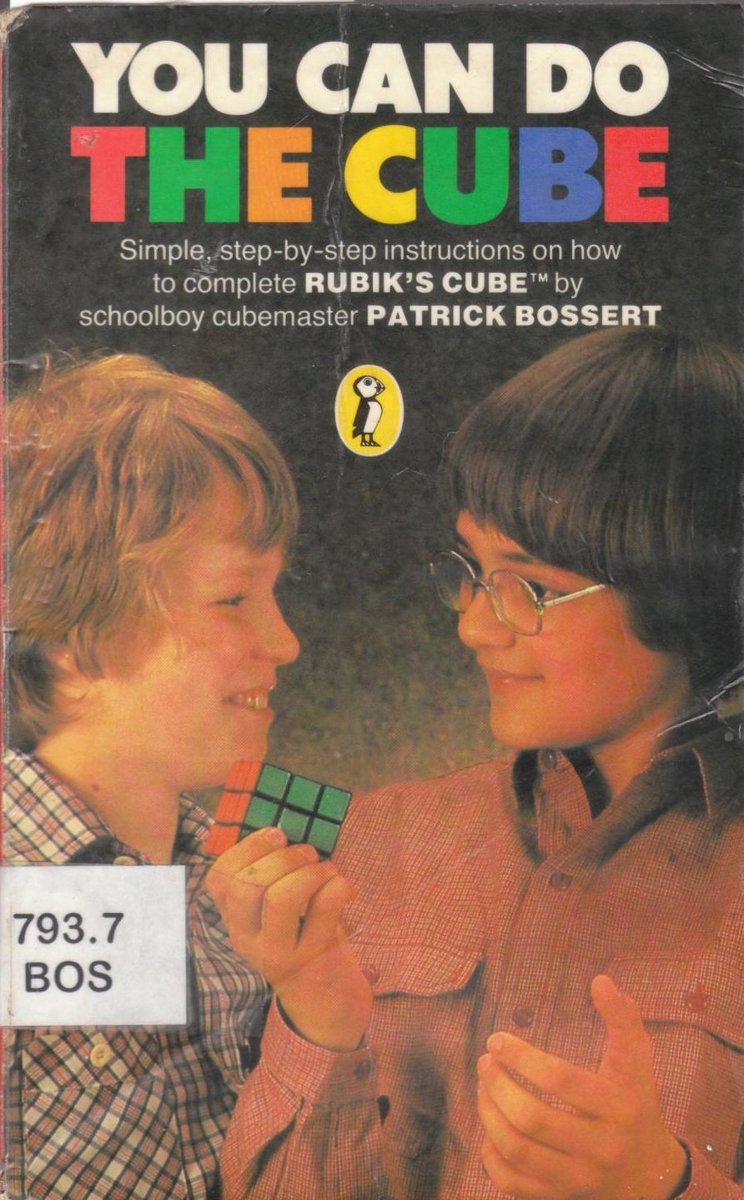

Algorithms are simply sets of well-defined rules used (often in combinations) to solve well-defined problems, or to help make ill-defined problems more solvable. Rubik’s cube is solved through algorithms, as are Google searches.

The key to their power is that they are unambiguous: rules is rules! Yet used repeatedly and in combinations they are extremely powerful. And they’re not always tied to the thing they operate on: a good algorithm can be applied to anything.

Algorithms have been used for millennia, but it was the work of neuroscientists David Marr and Tomaso Poggio in the 1970s that made them very interesting to cognitive psychologists. Could they help us see complex biological systems in a new light?

The brain is very complex and we often conceptualise it through metaphors. It’s been compared to a hydraulic system, a telephone exchange, a computer, or whatever else was handy to compare it with. But what if we had no metaphors? What if we just looked at the thing-in-itself?

Well that’s where Marr and Poggio come in. Their big idea was the Tri-Level Hypothesis - ‘the three levels of explanation’ for the brain and, by extension, any complex system. There are three ways to look at anything and the trick is to use the best way for the job in hand.

First there’s a computational level: what does the system actually do and why? Then there’s the algorithmic level: how does it do it and what rules does it use? Finally there’s the implementational level: how is the system physically realised?

Marr was very interested in human vision, where for decades psychologists had studied the computational and the implementational level of the system. Marr’s breakthrough was to start at the algorithmic: what are the mathematical rules neurons use to process visual inputs?

The answers have led to the 21st Century as we know it. From A.I. to Google, pattern recognition to high-frequency trading, these kind of algorithms have created the connected, predictive, high-data society we now inhabit.

And that’s now being applied to writing.

And that’s now being applied to writing.

What is a story? Well it’s a complex system: it has many variables, many linkages, and many ways of sequencing and synchronising the elements into a satisfactory whole. To write a story is to set out on a Hero’s Journey.

And like the Hero’s Journey we tend to focus on what the story should do and why. We work on the computational level: with our storyboards and character biographies and story arcs. We treat the story as a self-contained world that has to function as a book.

But stories don’t just live on the page, they also exist in the reader’s mind as they read them. And if the reader is on social media the story has another existence in the social web as we chat with other people about them. It’s all very meta.

And it’s this meta world - ‘fandom’ - that has led to writers thinking much more carefully about the algorithmic side of storytelling. Are there well-defined rulesets we can repeatedly use to hook the fandom, regardless of the story? Is that the real secret of modern writing?

Well if your social media feed is full of “7 amazing steps to plot creation” posts, or “13 lessons from the best book you’ve never read” listicles, then you may think this is already happening. Immediate narrative gratification is very much in vogue.

Many story algorithms are straight-up steals from the streaming services. For example world-building seems to be at a premium in a lot of modern writing; immersive settings with M.C. Escher levels of complexity.

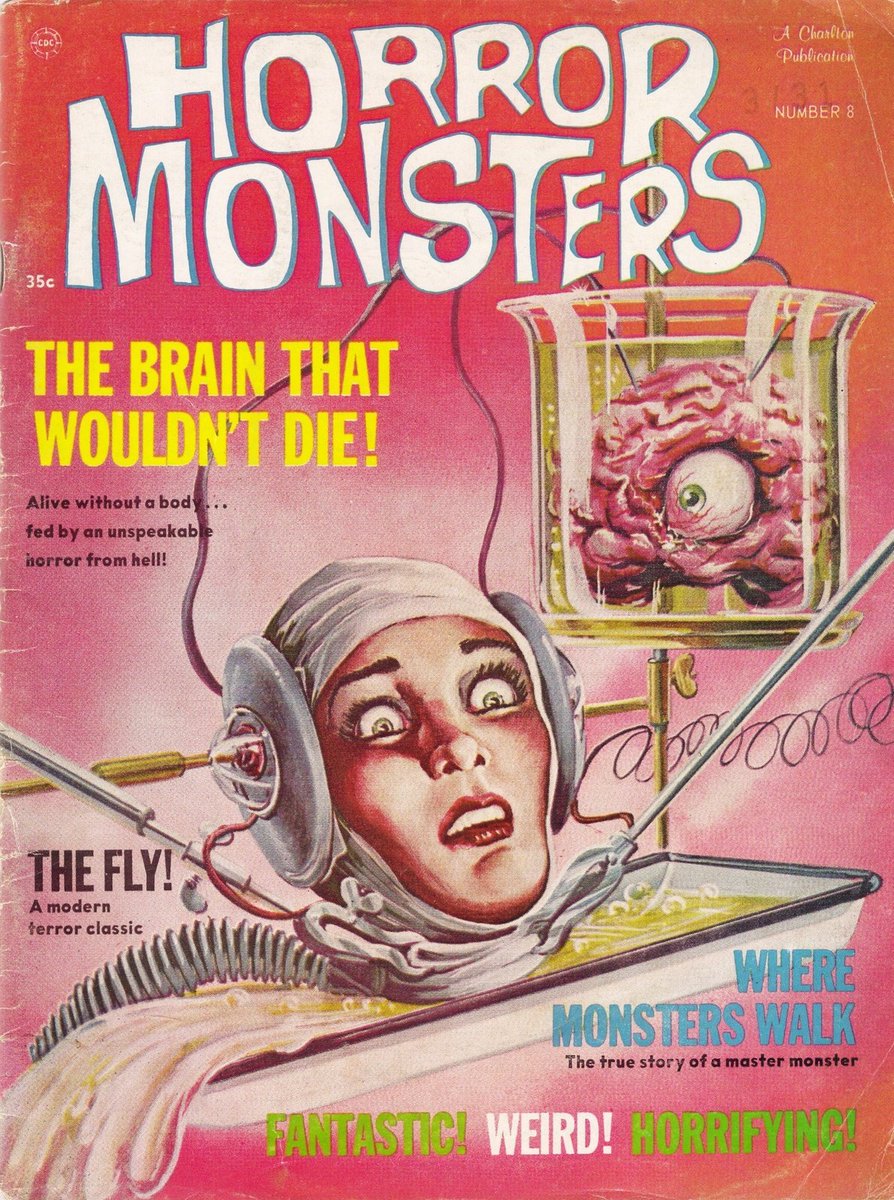

Happenstance has almost vanished: everything has a reason, every is significant, everything is a clue. Stuff doesn’t just happen in today’s stories and even if it does it’s a metaphor for something else. It’s like living in Philip K Dick’s VALIS.

But the result is interesting: it’s as if we are expecting lots of tricks to be played on us in the story and we are waiting to score the author for their quality of trickery. And we don’t just want smoke and mirrors, we want cyphers and holograms too.

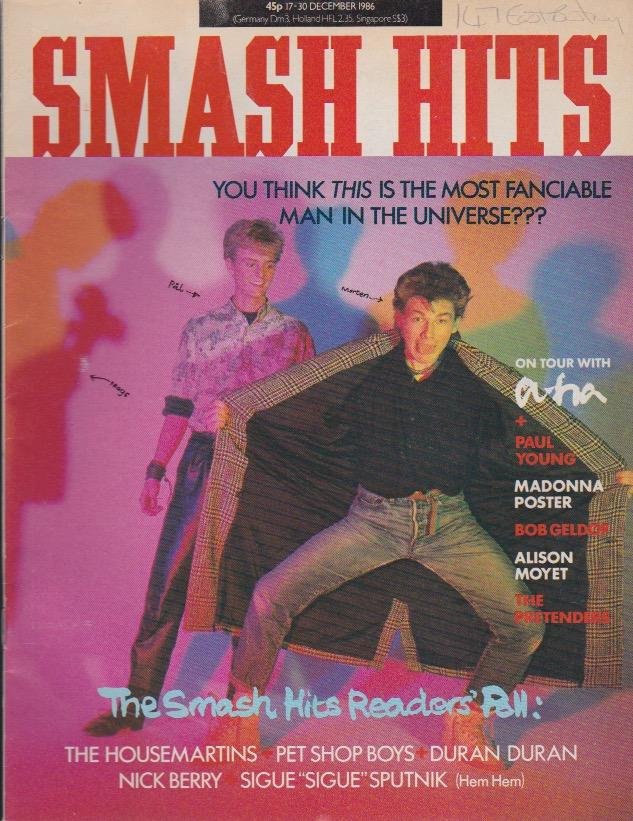

We also want riffs: lots of knowing looks and winks to other books, movies and cultural tropes. We like stories that touch on modern cultural themes, even if they never explore them in depth. A light sprinkling of zeitgeist is enough.

‘Compact’ is maybe a good word to describe algorithmic stories: Every story artefact has multiple meanings, signifiers and references condensed into it. Meaning is everywhere, and wants your attention at all times.

As a result we have worlds where even minor characters, plot points or themes have multiple, sometimes superficial layers of meaning poking out of them. Everything crackles and glitches with story energy. Even the exposition scenes are steeped in drama and tension.

Now this might be dismissed as gimmick-based literature: lots of cute hooks, edgy characters, predictably unpredictable plot twists delivered on cue, all crammed into a 3-act format. But the effect is very important…

Because most people don’t finish a book. They mean to, but it’s always a struggle. The role of these algorithms is to make you finish the story. Even if you’re bored, tired or uninterested you want the satisfaction of seeing the story resolution.

All these fragments you’ve been served up, all these expectations of meaning, mystery and trickery: where do they go? Curiosity is incredibly motivating and these story algorithms hack that instinct. Where will this trick of a book end?

That, sadly, is the weak spot of this type of book. It can be almost impossible to resolve everything in a satisfactory way when you have hinted at so much in the building of an immersive story.

But why end it?

But why end it?

If the streaming services have taught us one thing it’s that spin-offs, prequels, and multiverse narratives are very intriguing and very profitable. The story payoff isn’t in the story’s end. There is no end. It’s one conundrum after another.

Modern storytelling has fallen in love with fractals. And how do you make a fractal? You use a simple, recursive algorithm. The pleasure is in the pattern, not the shape. It may not be the best way to tell a story, but right now it’s certainly popular.

More tales another time…

More tales another time…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh