Of all the diseases, the ONE that is most often thought as something that can be treated with #exercise is, of course, #obesity. But, instead, obesity is commonly treated with #drugs. Who would like to know more about the history of FDA-approved obesity drugs in the US? A thread!

For economy, let's skip the part about the 1st wave of obesity drugs being based on amphetamine & methamphetamine (to speed up metabolic rate), either alone or in combination with a "downer," to balance the stimulatory effect of the meth/amphetamine on the central nervous system.

In 1959, phentermine (an amphetamine analogue, with less addictive potential) was introduced. It stimulates the release of norepinephrine (primarily), and dopamine and serotonin (secondarily) in the brain. Acts as an appetite suppressant.

In 1973, the FDA, based on newly implemented procedures, approves another amphetamine-based drug, fenfluramine. But, the drug is withdrawn in 1977 (along with other amphetamine-based obesity drugs) due to the absence of compelling safety data about their addictive potential.

Everything changed in 1992 when Michael Weintraub published a series of papers from a study showing that the combination of fenfluramine and phentermine led to substantial weight loss compared to placebo, without major side-effects. A blockbuster drug cocktail was born: fen-phen!

By 1996, an estimated 18 million prescriptions for fenfluramine (Pondimin) were written in the US! So, the FDA receives an application for its dextrorotatory version, dexfenfluramine, by Interneuron Pharmaceuticals. The drug was to be marketed by American Home Products as Redux.

The FDA first rejects the application for dexfenfluramine based on concerns about primary pulmonary hypertension and neurotoxicity but the negative decision is reversed almost immediately, Redux is approved, and sales soar!

In September 1996, TIME magazine has Redux on the cover. Millions of middle-aged adults in the US, primarily women, wanting to lose 5-10 lbs, take Redux in combination with phentermine. Everyone's happy because the drug combination evidently works!

But the party was to be short-lived. In August 1996, the New England Journal of Medicine publishes a European study showing that, as feared by the FDA advisory committee, the drugs raise the risk of primary pulmonary hypertension. Later studies show effects on heart valves.

An editorial commissioned by the NEJM editors becomes one of the highest-profile scandals involving conflict-of-interest. JoAnn Manson (Harvard) and Gerald Faich (UPenn) claim that the benefits of the drugs outweigh the risk but don't declare their links to the drug manufacturer.

The financial ties of Manson and Faich to the drug manufacturer (& its American subsidiaries) are discovered by journalists, who then inform the editors of NEJM. If you haven't, you should read the books published by Marcia Angell and Jerome Kassirer after their terms as editors.

In a subsequent invited paper in Epidemiology, JoAnn Manson attributes the slip-up to nothing more than a "series of misunderstandings." Of course, she remains a towering figure in the obesity field.

A year later, in September 1997, the FDA finally announces the withdrawal of fenfluramine and dexfenfluramine (Redux) from the US market, breaking up the fen-phen drug combo.

With well over 100 deaths in the US and numerous hospitalizations linked to fen-phen, the story becomes an injury attorney's dream. Servier, Interneuron Pharmaceuticals, American Home Products, Wyeth are forced to pay billions of dollars in compensation deals.

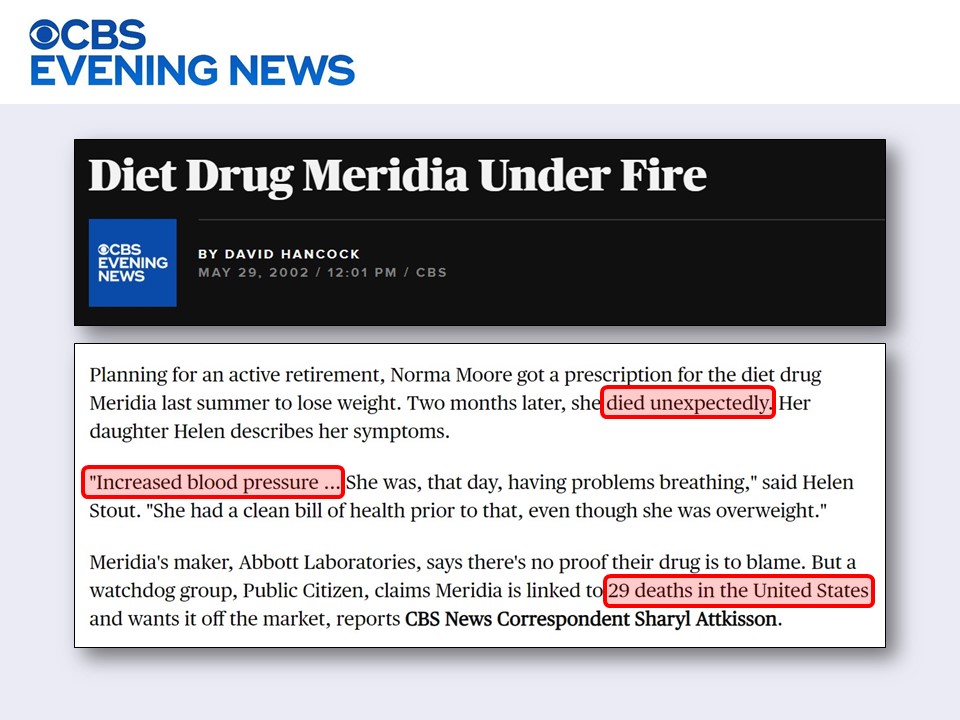

Despite massive scandal and the negative publicity, the FDA feels the pressure to approve a drug for obesity, so as quickly as it pulled Redux (September 1997), it approved sibutramin (Meridia), an SNRI from Abbott Laboratories (November 1997).

Despite concerns about spikes in blood pressure and heart rate expressed by the advisory committee, the agency approved based on the conviction that "the benefits outweigh the risks." By now, you should know where this is going, right?

Yes, people started dying. The spikes in blood pressure were not "inconsequential," to a large measure because it is impossible to police who will pressure their physician for the magic "diet drug."

The run of sibutramin (Meridia) lasted until 2010, when it was withdrawn. Contrary to the rationale originally expressed by the FDA to justify the approval of the drug, now the FDA said that the "modest weight loss" cannot justify the "risk of heart attack or stroke." What irony!

Parenthetically, in 2006, the European Medicines Evaluation Agency (EMA) had the brilliant idea to approve a blocker of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor called rimonabant, marketed as Acomplia (Sanofi-Aventis).

As quickly as 2008, it became evident that, if you block the cannabinoid receptors, bad things happen; people start trying to kill themselves. So, although Aventis had applied to get FDA approval, the drug was withdrawn from Europe and the FDA application was never evaluated.

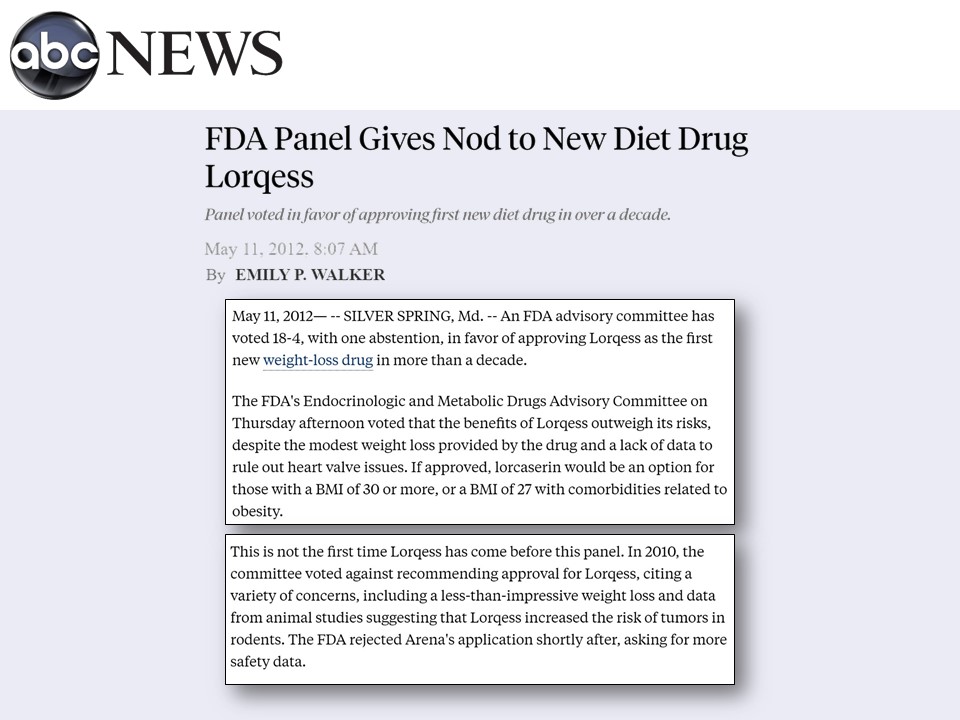

Around 2010, at least three drug hopefuls are working the FDA process: (1) lorcaserin by Eisai / Arena Pharmaceuticals, (2) the combination of phentermine / topiramate by Vivus, and (3) the combination of naltrexone / bupropion by Orexigen / Takeda. All are fascinating stories!

Lorcaserin, which was going to be marketed as Lorqess, came in front of the FDA in 2010. It was rejected due to marginal effectiveness and elevated risk of cancer.

But given that, once again, there was pressure to have some obesity drugs available in the market, the drug was quickly approved in 2012, despite the concerns.

The combination of the good-old phentermine (yes, the "phen" from fen-phen) and topiramate (anti-epileptic), which was to be marketed as Qnexa, gets a rejection in 2010 due to concerns about birth defects (e.g., cleft palate) and cardiac problems.

But, in a familiar pattern, due to pressure to have obesity drugs in the market, the FDA quickly approves the drug combo. To shed the negative baggage, drugs that have a prior FDA rejection tend to be renamed after approval, so Qnexa became Qsymia.

Meanwhile, the combination of naltrexone (a blocker of the opioid receptor) and the antidepressant bupropion (Wellbutrin), developed by Orexigen / Takeda, which was to be marketed as Contrave, starts the process more slowly. It gets its initial rejection in 2011.

Obviously, the obesity "insiders" are well aware that there is activity in the obesity field. So, following the 2012 FDA approvals, the American Medical Association declares obesity a "disease" in 2013, hoping for better insurance coverage of the new drugs.

They time the announcement to coincide almost perfectly, in early June 2013, with the official introduction of Belviq (formerly Lorqess) and Qsymia (formerly Qnexa) to the US market.

Alas, earlier in 2013, Katherine Flegal of CDC, evidently not invited to the party, publishes a meta-analysis in JAMA, showing what researchers know as the "obesity paradox," namely that there's hardly any elevated risk at the BMI range of "overweight" or even "obesity class 1."

This phenomenon is well known and reliably established. By several indictors, it appears that mortality and health care costs are lowest at the BMI range we have come to consider as "over-weight."

Flegal was viciously attacked, with language and tactics that were entirely unprofessional. The main attackers were the superstars from the Harvard School of Public Health, including Walter Willett and ...yes, JoAnn Manson, who convened a press conference to discredit Flegal.

If you have a chance, read "The obesity wars and the education of a researcher: A personal account" by Katherine Flegal. It is truly shocking and eye-opening.

doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad…

doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad…

Meanwhile, the third drug, Contrave, earned FDA approval in 2014, despite concerns about cardiovascular problems. Orexigen promised to conduct a *subsequent* safety study, to show that Contrave does not raise the risk of heart problems.

Orexigen decides to inappropriate "peek" at the data after 25% had been collected, and thinks it's finding a cardiovascular benefit (!) rather than risk. Thinking they may get a patent, they file with the SEC and disclose the data! But analysis of the next 25% shows no benefit!

The FDA was furious. The Cleveland Clinic partners were furious. So, the trial was discontinued! Then, as this was not enough, Orexigen decides to also discontinue a second safety trial, called Convene!

Eventually, Orexigen filed for bankruptcy in 2018. As far as I know, the promised safety data have yet to be delivered to the FDA but the drug is still on the US market (contrave.com).

On the other hand, lorcaserin (Belviq, formerly Lorqess) was pulled from the market in 2020, after 7 years, precisely for the reason it had been initially rejected by the FDA: increased risk of cancer.

As one reads this amazing story (if you made it to this point), keep in mind that the FDA guideline for seeking regulatory approval for an obesity drug in the US, is that the drug arm of the trial should lose on average just 5% of body weight more than the placebo arm.

This fact, and the long and sad story I summarized here, should help underscore how CRUCIAL it is for exercise science to become a lot better at developing methods to keep individuals who are overweight or obese physically active. Talk to your students!

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh