If I were to pick one constantly reiterated assertion that has done the most to limit anthropologists' understanding of publishing, or of what it might take to pursue different models or forms of publishing, it's this one. #anthrotwitter

https://twitter.com/ElizabethCDunn/status/1412841211845656581

Wiley doesn't just profit: the majority of that profit goes back to the AAA & its sections, which in turn funds some of the editorial labor & other activities. Wiley is also undertaking the work of making scholarship readable, findable, placed in a particular info system, etc.

The real complain (+ others) is that Wiley charges too much for its services, which scholars benefit from & have come to expect, even when they have little sense of what is involved. And "digital" has added another layer of abstraction to these services. eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/19432

Anthropologist aren't alone in making this assertion: it is loose across academia. Here's an economist: "All Elsevier does really is a little bit of text editing and putting the papers online." [One of my attempts to get at the problems w/ this assertion: hcommons.org/deposits/item/…]

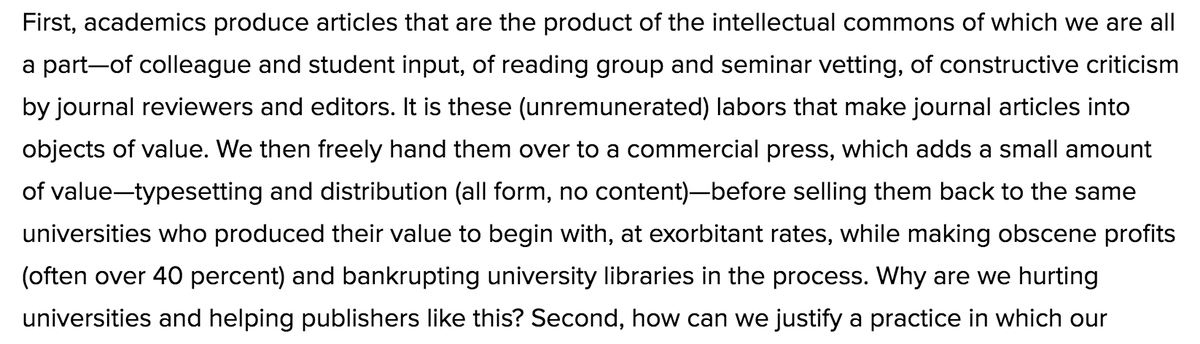

Back to the another anthro example, which has the benefit of getting at what I see as the heart of the problem: what it is that scholars value (content, not form) vs. what publishers mostly work on (documents & infrastructure [form], not content). [From doi.org/10.14506/ca30.…]

Note that the "intellectual commons" has to be abstracted from the tangle of material infrastructures that enables it (in this case, both the university & publishers) for content to float freely away from form. Scholarship becomes pure mind, free of corrupting materiality.

Since my time at @culanth, I've been trying to get scholars to rethink their implicit idealism when it comes to scholarship. All scholarship is materially embodied & embedded in the world, just like the scholars who produce it. [From doi.org/10.14506/ca29.…]

Until scholars better understand what publishers do (which is, by design, infrastructurally invisible), they will continue to devalue what publishers contribute to the production & circulation of scholarship, or how it might be done differently.

Back to Dr. Dunn's tweet: We need to list the labors of publishers alongside those of scholars. When I calculated it for @culanth, 80-85% of the costs of the journal was to compensate publishing labor (managing editor, editorial assistant, developer, designer, compositor, etc).

Open access doesn't mean those costs go away; rather, OA models aim to fund services (expenditures of labor), instead of the production & protection of intellectual property. OA can be done for-profit or not, be ethical or not, tackle inequalities or not, be high-quality or not.

The assertion that publishers do nothing is a great way to maintain ignorance of what publishing is, how its accomplished, & how it might actually shift to something else. It is a distraction & hinderance to strategic action by those interested in this something else.

[To be clear: I hold nothing against professors Dunn, Allison, or Piot. I think their analysis is faulty & worry a lot abt the consequences. Also, this is an extremely qualified defense of big commercial publishers: we can build something better.]

https://twitter.com/timelfen/status/1071497653672861696?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh