This is actually a good example of a tweet thread that contains ideas that are all correct but are not actually useful.

I can assure you, as an org designer, this is NOT how good org designers actually think about incentives.

I can assure you, as an org designer, this is NOT how good org designers actually think about incentives.

https://twitter.com/SahilBloom/status/1434847309976702980

To establish some credibility: I built a debate club in high school, which imploded.

I thought, "hmm, this seems like a useful skill to learn".

I then built the NUS Hackers, which has persisted for 8 years now, and remains the best place to hire software engineers in Singapore.

I thought, "hmm, this seems like a useful skill to learn".

I then built the NUS Hackers, which has persisted for 8 years now, and remains the best place to hire software engineers in Singapore.

And then I went to Vietnam, built out an engineering office there, and tweaked the departments adjacent to our office, and now, 3 years later, the org has retained 75% of the people I hired, and are still run using many of the same policies/incentives I designed.

To be fair to Bloom, perhaps the incentive design he talks about applies to deal-making. Or perhaps the ideas are meant in an atomised, theoretical way.

But every idea in there is almost certainly going to trip you up in bad ways if you tried to apply them to your org.

But every idea in there is almost certainly going to trip you up in bad ways if you tried to apply them to your org.

The basic tools when it comes to org design looks like this:

1. You have an accurate model of the people you are dealing with. This is context dependent. Salespeople respond to incentives differently from engineers.

2. You have the ability to think in terms of systems.

1. You have an accurate model of the people you are dealing with. This is context dependent. Salespeople respond to incentives differently from engineers.

2. You have the ability to think in terms of systems.

3. Finally, you have an accurate understanding of how culture works.

The shape of the expertise is like this: you design through a step-by-step unfolding. Over time, you design policies, shape culture, and nudge behaviour through meetings, one-on-ones, and actions.

The shape of the expertise is like this: you design through a step-by-step unfolding. Over time, you design policies, shape culture, and nudge behaviour through meetings, one-on-ones, and actions.

The most important nuance is to recognise bad behaviours early and nip them in the bud by course-correcting.

It is useless to talk about the cobra effect, or about Goodwin's law, or about skin in the game if you don't have these skills pinned down.

In fact, it is not necessary.

It is useless to talk about the cobra effect, or about Goodwin's law, or about skin in the game if you don't have these skills pinned down.

In fact, it is not necessary.

Because you are able to model the behaviour of the humans you are dealing with, you understand the system you are modifying, and you understand how to mould culture, none of these issues will come up.

These are just frameworks that sound intelligent but are not useful.

These are just frameworks that sound intelligent but are not useful.

"Wait, but Cedric, Goodwin's law is a thing! Other intelligent people talk about it!"

Yes, but the way you defeat Goodwin's law is not by talking about Goodwin's law. Bloom talks about Amazon in his tweet thread. Amazon actually deals with Goodwin's law quite well.

Yes, but the way you defeat Goodwin's law is not by talking about Goodwin's law. Bloom talks about Amazon in his tweet thread. Amazon actually deals with Goodwin's law quite well.

In Working Backwards, Colin Bryar and Bill Carr dedicated an entire chapter to how they think about metrics.

The number of times they mention Goodwin's Law: 0.

Amazon has a process they call DMAIC. The book tells the story of the step-by-step unfolding that led them to it.

The number of times they mention Goodwin's Law: 0.

Amazon has a process they call DMAIC. The book tells the story of the step-by-step unfolding that led them to it.

Bryar and Carr are extremely believable, by the way. They were in the room when the 6-pager was designed, when the decentralised org in Amazon was built, and when Amazon's approach to metrics was still being built out.

DMAIC enables them to sidestep Goodwin's law.

DMAIC enables them to sidestep Goodwin's law.

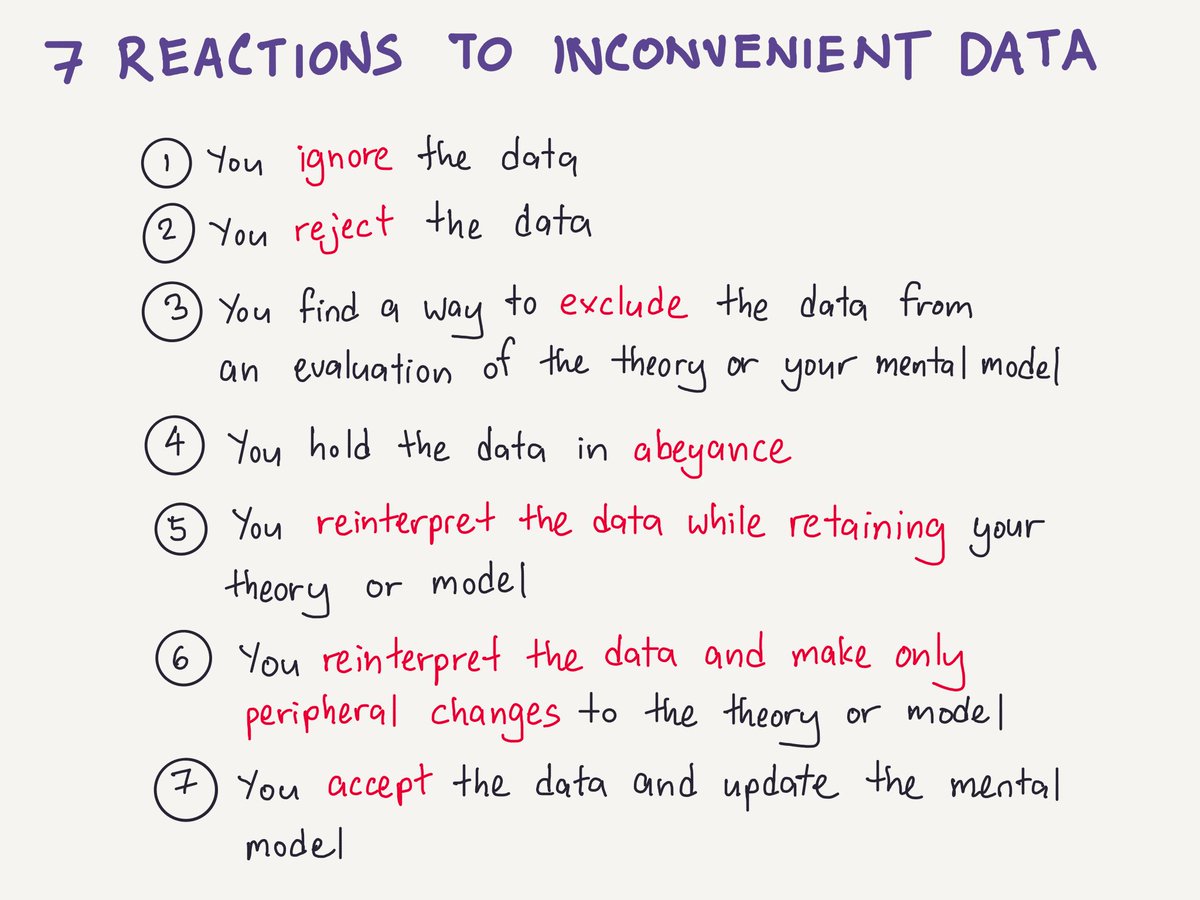

Most people, with no org design background, would read Working Backwards as a 'manual of techniques to apply'.

Org designers read Working Backwards as an accounting of the step-by-step unfolding that LED Amazon to design those systems.

My summary: commoncog.com/blog/working-b…

Org designers read Working Backwards as an accounting of the step-by-step unfolding that LED Amazon to design those systems.

My summary: commoncog.com/blog/working-b…

Novice org designers would read stories of misaligned incentives and go "Ha! What a bad idea! Use these frameworks!"

Experienced org designers would read stories of misaligned incentives and ask: "How did they get there and what processes did they try after that incident?"

Experienced org designers would read stories of misaligned incentives and ask: "How did they get there and what processes did they try after that incident?"

I spend a lot of time talking about believability. I said that you should not pay attention to ideas from people who:

- Have not had at least 3 successes in the domain, and

- Have a coherent explanation when probed.

This is not my idea, it's Ray Dalio's: commoncog.com/blog/believabi…

- Have not had at least 3 successes in the domain, and

- Have a coherent explanation when probed.

This is not my idea, it's Ray Dalio's: commoncog.com/blog/believabi…

But I think this thread is a good example of why.

The instant I read Bloom's thread, I was like "ok, this seems ... off."

Every idea was correct.

Every idea sounded intelligent.

Every idea was also quite useless.

The instant I read Bloom's thread, I was like "ok, this seems ... off."

Every idea was correct.

Every idea sounded intelligent.

Every idea was also quite useless.

And the reason for that is because the WAY you use the ideas are not the way you might think they should be applied.

The shape of the expertise of org-design is a step-by-step unfolding. Not taking that into account is a novice mistake.

The shape of the expertise of org-design is a step-by-step unfolding. Not taking that into account is a novice mistake.

Why this is the case is a different thread for another day.

(The basic idea is that nobody can perfectly predict org response to incentives because orgs + org culture are somewhat complex and dynamic and adaptive. So you need to iterate to see how the system adapts).

(The basic idea is that nobody can perfectly predict org response to incentives because orgs + org culture are somewhat complex and dynamic and adaptive. So you need to iterate to see how the system adapts).

Anyway: all of this is to say, be careful who you read. Make sure they are believable in the domain. Or you might be led astray by correct ideas that are just not useful because they've never been put to practice.

The end.

The end.

Ahh, god, I meant Goodhart's law. You would think I would have known about this, having written about it in the past.

Correction: I meant Goodhart's Law, not Goodwin's law.

I should've known better! And I say this as someone who summarised Mainheim and Garrabrant's "Categorizing Variants of Goodhart's Law" paper in the past!

I should've known better! And I say this as someone who summarised Mainheim and Garrabrant's "Categorizing Variants of Goodhart's Law" paper in the past!

https://twitter.com/ejames_c/status/1435122793939537925?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh