1 - It's time for #threadtalk! Today's topic, the Grand Dame of Damask: Anna Maria Garthwaite.

This silk icon has quite a tale, but so does her stomping ground of Spitalfields, London.

And beyond the frippery? The horrors of 18thC England: persecution, riots & taxes🕍🔪💷

This silk icon has quite a tale, but so does her stomping ground of Spitalfields, London.

And beyond the frippery? The horrors of 18thC England: persecution, riots & taxes🕍🔪💷

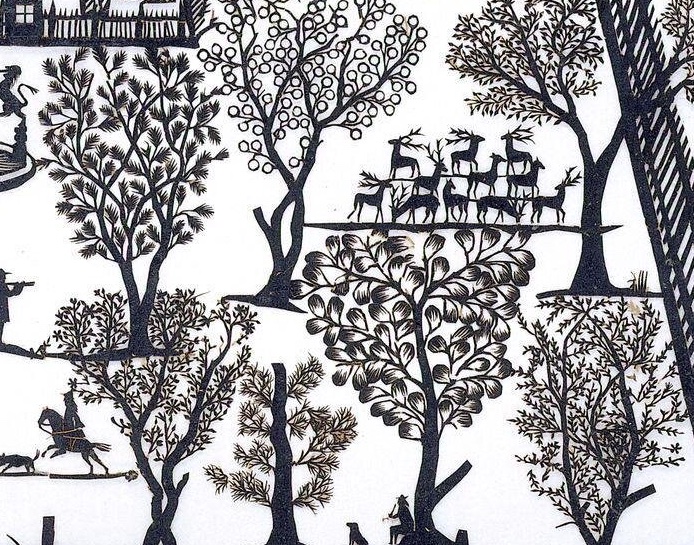

2 - Anna Maria was born in 1688 in Lincolnshire, to Rev. Ephraim Garthwaite & Rejoyce (rad name). The family was well to do & Anna Maria would have had a basic education. She showed early artistic prowess, like in this 1707 cut-paper work of a village w/remarkable detail.

3 - I mean, look at the incredible detail on this. Each and every tree has a different shape & leaf pattern, far beyond basic representation. The little horse and rider, the delicate horns on the deer. Painstaking work here that foreshadows the skill of an artist, to be certain.

4 - Besides the above work (made at 17) We know little of Anna Maria until she moves to Spitalfields at 40.

As a spinster. Unmarried and uninterested, Anna Maria sets to work as a silk designer with no known training, establishing herself in a field dominated by men. Unheard of.

As a spinster. Unmarried and uninterested, Anna Maria sets to work as a silk designer with no known training, establishing herself in a field dominated by men. Unheard of.

5 - Working primarily in watercolor, her designs helped establish the "English" style of Rococo. Unlike denser French florals, her works drew a bit more on nature & plainer backgrounds (though certainly still with a heavy influence from the East). Below, V&A, watercolor, 1739.

6 - Anna Maria's watercolors, which the V&A has dozens, are beautifully mathematic. Though not a weaver herself, she would work closely with silk weavers to achieve the right effect.

This pattern here, for example, gives you an idea of what a design drawn out might look like.

This pattern here, for example, gives you an idea of what a design drawn out might look like.

7 - Anna Maria was astoundingly prolific, producing over 80 patterns a year. The classic "S" shape of the period is often seen in her work & her silks were wildly popular.

But why silk, and why Spitalfields? That question takes us back before Anna Maria. And to France.

But why silk, and why Spitalfields? That question takes us back before Anna Maria. And to France.

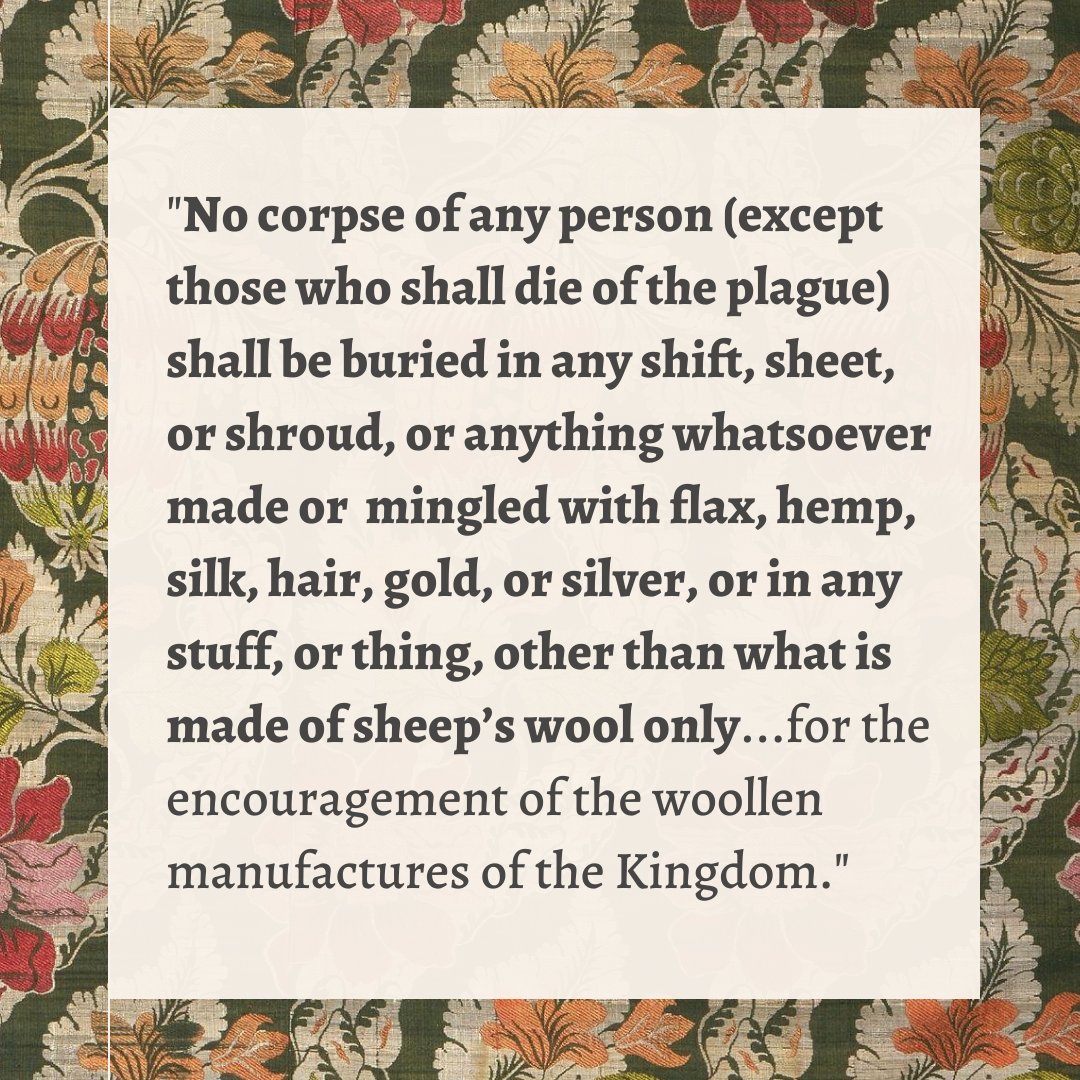

8 - England was not a silk-producing country, in spite of their best efforts. So wool remained THE industry.

Plus, there were laws. Because wool was *patriotic* (read: profitable). All servants had to wear wool, and even the dead did, as per Acts passed (1621, 1666, onward)

Plus, there were laws. Because wool was *patriotic* (read: profitable). All servants had to wear wool, and even the dead did, as per Acts passed (1621, 1666, onward)

9 - But this dyed-in-the-wool stubbornness caused issues, because silk is gorgeous & rich people love it. France was raking in the $$$.

Turns out religious persecution can be profitable, though, am I right?

Enter the Huguenots (feat: Millais' super romanticized painting below)

Turns out religious persecution can be profitable, though, am I right?

Enter the Huguenots (feat: Millais' super romanticized painting below)

10 - The French Kings did not like their Protestants (Huguenots). By "did not like" I mean "massacred & persecuted relentlessly". When good ol' Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685, it destroyed Protestant churches, schools & protections. Huguenots had nowhere to go.

11 - So Huguenot families did what refugees still do today: they risked it all & left. Some found their way to Quebec (my ancestors in Arcadia!); others Some families smuggled themselves along wine casks on ships to London, with only their skills.

Silk-weaving chief among them.

Silk-weaving chief among them.

12 - By 1687 there were over 16K French refugees in London, mostly around Spitalfields. Many of the weavers came from Lyons & Tours, known for their incredible weaving & developed methods for lustering silk (adding shimmer!). A number of prominent designers were also refugees.

13 - Although some (mostly men) refugees made bank as Masters, working conditions were rough for (many women) weavers. Tenements were clean--essential for silk weaving--but crowded. Three or four families in a house, or small, one or two room cottages with big looms inside.

14 - Londoners seemed generally to accept the Huguenots as hard workers. However.

Mobs still rose up against the French time to time, & often against women in the worst possible ways. Sometimes resulting in death.

(Below: Map of Huguenots in Spitalfields.)

Mobs still rose up against the French time to time, & often against women in the worst possible ways. Sometimes resulting in death.

(Below: Map of Huguenots in Spitalfields.)

15 - Which brings us back to women. Because the world Anna Maria Garthwaite lived in & influenced was charged, especially regarding women in fashion, & it had everything to do with fabric & privilege.

This is where the story gets really nasty & it starts with calico/chintz.

This is where the story gets really nasty & it starts with calico/chintz.

16 - As a refresher, chintz (AKA calico) came from India. These fabrics were printed or painted cotton, so they were cheaper than silk, but had VERY similar patterns.

Mostly b/c the silk patterns were appropriated from India in the first place.

Mostly b/c the silk patterns were appropriated from India in the first place.

https://twitter.com/NataniaBarron/status/1353866167568445441

17 - By 1719, calicos were disrupting the entire market. They were gorgeous, fashionable & everyone could afford them.

Silk? Not so much. Super labor intensive. Made of cocoons. Wool? Patriotic, maybe. But not ideal for prints. Certainly not light and airy.

So what to do?

Silk? Not so much. Super labor intensive. Made of cocoons. Wool? Patriotic, maybe. But not ideal for prints. Certainly not light and airy.

So what to do?

18 - What did the Spitalfields weavers do to combat the issues?

They innovated!

JK. They mobilized a mob of 4,000 and terrorized women wearing calico by throwing ink, aqua fortis (nitric acid) & "other fluids" on them, tearing gowns off womens' backs.

And kept doing it.

They innovated!

JK. They mobilized a mob of 4,000 and terrorized women wearing calico by throwing ink, aqua fortis (nitric acid) & "other fluids" on them, tearing gowns off womens' backs.

And kept doing it.

19 - "The Calico Riots" went on & women across all social lines were the targets.

This lead to retaliation, but instead of opting for team calico, Parliament went for team silk.

In SUPER NOT SURPRISING NEWS the fabric of the gentry got protected & calico got banned.

This lead to retaliation, but instead of opting for team calico, Parliament went for team silk.

In SUPER NOT SURPRISING NEWS the fabric of the gentry got protected & calico got banned.

20 - Guilds were involved, of course, & many guilds were hardly more than organized crime. The politics involved are complex. But terrible.

Of course, it didn't stop women from wearing chintz. And people still smuggled it (and died for it).

Fabric history, y'all. It's a trip.

Of course, it didn't stop women from wearing chintz. And people still smuggled it (and died for it).

Fabric history, y'all. It's a trip.

21 - This is not to detract from Anna Maria Garthwaite's impressive contribution. A self-made woman, a spinster, a homeowner, an autodidact, she took risks to be visible, to make a living; she was an outsider in a way, too. But she chose silk.

(pictured, not her, but her damask)

(pictured, not her, but her damask)

22 - But just like any gown of the period, all of this has layers. Cloth is capital. Laws, taxes, Kings, religion--all of it moves the dial.

And when women take charge & are visible, things happen. Anna Maria chose spinsterhood & art. Pro-calico women chose fashion over safety.

And when women take charge & are visible, things happen. Anna Maria chose spinsterhood & art. Pro-calico women chose fashion over safety.

23 - Let's look at some gowns, shall we?

First, a Spitalfields robe à la française. Silk extended tabby (gros de Tours) with liseré self-patterning and brocading in silver lamella and filé. From ROM collections ,1750.

I can't with this one. Literally can't. Yellowgasm. Lord.

First, a Spitalfields robe à la française. Silk extended tabby (gros de Tours) with liseré self-patterning and brocading in silver lamella and filé. From ROM collections ,1750.

I can't with this one. Literally can't. Yellowgasm. Lord.

24 - Spitalfields. This one looks so calico it hurts. Like, take this silk but make it LOOK COTTON. Altered, like many you'll see. I'm a sucker for roses.

Pink gros de tours silk with flush effect, ivory flowers, Spitalfields, 1740s; fancy dress additions 1950s, via the V&A.

Pink gros de tours silk with flush effect, ivory flowers, Spitalfields, 1740s; fancy dress additions 1950s, via the V&A.

25 - This is a Garthwaite gown, but I wish someone would turn off the flash over at the V&A.

Their note: 1744 (designed), 1744-1745 (weaving), 1745-1750 (sewing), 1760s (altered), 1870-1910 (altered) - again, these prized silks get altered & nipped & tucked! Love the colors.

Their note: 1744 (designed), 1744-1745 (weaving), 1745-1750 (sewing), 1760s (altered), 1870-1910 (altered) - again, these prized silks get altered & nipped & tucked! Love the colors.

26 - My personal favorites from Garthwaite are her monochrome damasks, like this ladies banyan. Not only is it rare to see one from this period, the green is just incredible. Woven 1740, made a decade later.

You can see the Japanese influence here. Would wear.

You can see the Japanese influence here. Would wear.

27 - Here's a trip: 1752 (designed), 1752 (weaving), 1755 - 1775 (sewing), 1895 - 1900 (reconstructed)

Figured silk, probably once a sack dress, originally a Garthwaite dress. Reconstructed in the late 19th century! Talk about a lifetime. I'd recognize that design anywhere.

Figured silk, probably once a sack dress, originally a Garthwaite dress. Reconstructed in the late 19th century! Talk about a lifetime. I'd recognize that design anywhere.

28 - This is another Natania Dreamy Dress. Can't say for sure if it's Spitalfields, but it is British. I can't get enough of the design on this one, because it feels so modern and whimsical. From 1770-75. The metallic thread (gold!) is all so shiny!

29 - Yet another stunner in simplicity. I love that the pattern makes the dress, showing off Garthwaite's art.

Made originally as a sack dress, and then altered in the 1780s, it still holds. It's brocaded satin, so basically I would pay lots of money to be allowed to touch it.

Made originally as a sack dress, and then altered in the 1780s, it still holds. It's brocaded satin, so basically I would pay lots of money to be allowed to touch it.

30 - I would also like to discuss these shoes. Because. I mean. ::flailing::

The way the pattern! The color! The heel! c. 1735. I'm pretty sure these are actually imbued with magic.

The way the pattern! The color! The heel! c. 1735. I'm pretty sure these are actually imbued with magic.

31 - Okay, I could go on, but it's time for sources. This is a big subject, and I literally dug into dissertations for it. So here we go:

Sources -

Anna Maria Garthwaite

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anna_Mari…

eastendwomensmuseum.org/blog/2020/6/4/…

eastendwomensmuseum.org/blog/2020/9/23…

artsandculture.google.com/entity/anna-ma…

Sources -

Anna Maria Garthwaite

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anna_Mari…

eastendwomensmuseum.org/blog/2020/6/4/…

eastendwomensmuseum.org/blog/2020/9/23…

artsandculture.google.com/entity/anna-ma…

32 - Anna Maria Garthwaite (cont'd)

…ofessorhedgehogsjournal.wordpress.com/2020/11/04/ann…

blog.courtauld.ac.uk/documentingfas…

skyeoneill.com/blog/2017/11/1…

vam.ac.uk/blog/textiles-…

Spitalfields

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spitalfie…

panmacmillan.com/blogs/history/…

british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol2…

sas-space.sas.ac.uk/5774/1/Eppie__…

era.library.ualberta.ca/items/ef2ffbd4…

…ofessorhedgehogsjournal.wordpress.com/2020/11/04/ann…

blog.courtauld.ac.uk/documentingfas…

skyeoneill.com/blog/2017/11/1…

vam.ac.uk/blog/textiles-…

Spitalfields

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spitalfie…

panmacmillan.com/blogs/history/…

british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol2…

sas-space.sas.ac.uk/5774/1/Eppie__…

era.library.ualberta.ca/items/ef2ffbd4…

33 - Sources 3

Huguenots

ourmigrationstory.org.uk/oms/huguenot-s…

independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-n…

huguenotsociety.org.uk/history.html

family-tree.co.uk/how-to-guides/…

brh.org.uk/site/wp-conten…

citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/downlo…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Huguenot_…

huguenotsofspitalfields.org/learning-modal…

Rococo:

vam.ac.uk/articles/the-r…

Huguenots

ourmigrationstory.org.uk/oms/huguenot-s…

independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-n…

huguenotsociety.org.uk/history.html

family-tree.co.uk/how-to-guides/…

brh.org.uk/site/wp-conten…

citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/downlo…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Huguenot_…

huguenotsofspitalfields.org/learning-modal…

Rococo:

vam.ac.uk/articles/the-r…

34 - One more, because I love that the story of Spitalfields silk remade. Here's a gown from 1840, in America, over 100 years after the fabric was made, in the Boston MFA collection.

This is probably my favorite print to date--so Romantic, yet so Rococo. Anachronism in harmony.

This is probably my favorite print to date--so Romantic, yet so Rococo. Anachronism in harmony.

35 - Thanks for hanging out with me for tonight's #threadtalk for a look into the archives of #fashionhistory.

Remember to question beauty relentlessly, and that fashion is choice, expression, and rebellion. Sometimes, all rolled into one.

Remember to question beauty relentlessly, and that fashion is choice, expression, and rebellion. Sometimes, all rolled into one.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh