Pop quiz! Think about all the land occupied by buildings and infrastructure (cities, roads, factories). Takes up a lot of space. But how much, exactly?

Now think about all the land occupied for food production. How do the two compare? Which one is bigger, and by how much?

Answer: food production - and it's not even close!

About 1% of all habitable land is occupied by buildings and infrastructure. (Depends a bit on data sources and definitions, but it's at most a few percent)

As you might expect, not all of that land was just lying around waiting to be farmed or grazed. In fact, much of it was originally forest

Work by @Nramankutty and colleagues looks at natural land cover and asks how much of that is now used for food production doi.org/10.1029/2007GB…

For example, for tropical deciduous forest, they find that *half* of the roughly 6 million square km of original forest is now used for crops or pasture

But their work also shows that deforestation is not just about the tropics: in fact, 30-45% of what used to be temperate forests is now used for agriculture

A lot of that forest loss happened centuries ago, so we tend to forget about this. We're so used to seeing farming landscapes that we tend to assume they're "natural".

But it turns out forests originally covered a stunning 80% of the land!

At the end of 19th century, forest cover in Ireland had fallen to about 1%...

Nowadays, it's about 11% teagasc.ie/crops/forestry…

Agriculture wasn't the only driver of forest loss of course (whether in Ireland or elsewhere) - trees were cut for timber, firewood, etc.

But agriculture was and is an important driver of deforestation globally. Unfortunately even today expanding agricultural land is a major factor in deforestation (and all that implies, e.g. species extinction through habitat loss)

Equally unfortunately, once forests are gone, it's very hard to get them back, as recent research by @ForrestFleisch1 illustrates

https://twitter.com/ForrestFleisch1/status/1438191277754011662?s=20

(Be sure to also check the excellent @OurWorldInData explainers on forests here: ourworldindata.org/forests-and-de…)

OK, another pop quiz. Of all the agricultural land use globally, how much is for crops, and how much is land grazed by animals (cows, sheep, etc)?

Again, it's not even close: the vast majority is pasture/grazing

Depending on who you ask, the numbers vary a bit, but the overall pattern is clear: it's about 3.3 billion hectares of land for grazing, vs about 1.6 billion hectares for crops

For the Americans: one hectare is about... 2.5 fluid Fahrenheits @Ruecon

Correction - one hectare is about 2.5 acres, i.e. roughly two (American) football fields

Anyway, the bottom line is: with a growing population, we need to find ways to produce more food without using more land, because using more land is disastrous for the environment

Here's the good (and somewhat surprising) news: over the past few decades, we've actually been moving towards that goal!

Here is one of my favorite charts from our @OECDAgriculture report "Making Better Policies for Food Systems" dx.doi.org/10.1787/ddfba4…

Over the long run, population and land use probably grew more or less in tandem

But around 1960, something interesting happened!

Between 1960 and today, world population more than doubled. Over the same time period, global food production almost *quadrupled*

And yet, global agricultural land use increased by about 10-15% …

It's tempting to say "only" 10-15% but keep in mind that this is still an area twice the size of Greenland, with serious environmental consequences

But still, it's clear that the global food system managed to massively ramp up food production per unit of land, in the span of just a few decades

It's also consistent with data on meat production: most of the increase was pigs and poultry, which require way less land than ruminants (cows, sheep)

Now, before we all get too excited: producing more food per unit of land is not necessarily more sustainable. It could mean using more inputs, which could be bad news.

In general, there are two ways you could increase food production per unit of land: use more inputs per unit of land, or use resources more efficiently

When we talk about productivity/yield growth, people usually assume it means "more inputs" - e.g. more fertilizers, with all the environmental costs this entails

This means debates on food production tend to get framed as "intensive" versus "extensive". But it turns out this is not the best way of looking at things!

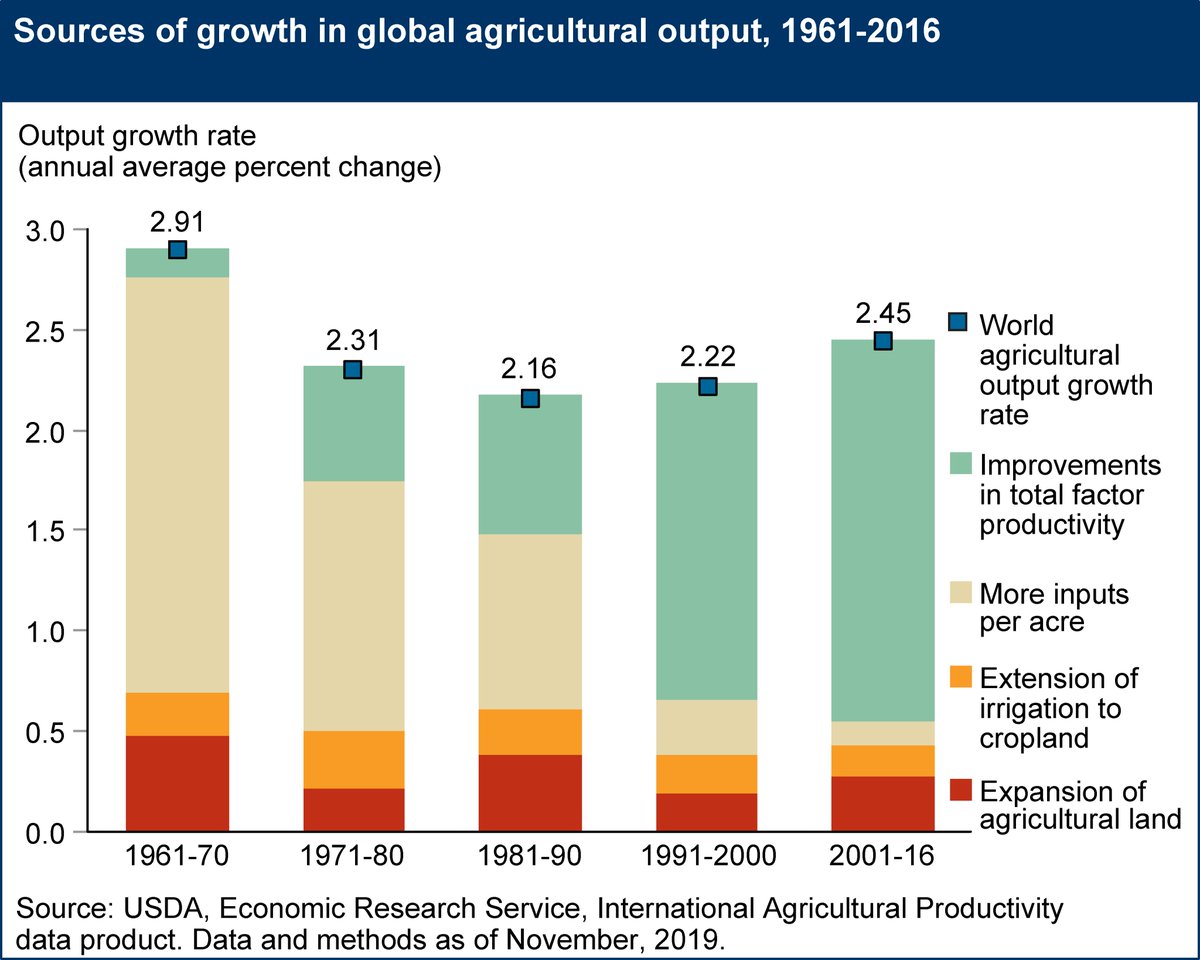

Here's a fascinating chart from @USDA_ERS estimating the relative role of different drivers of global agricultural production growth in the last few decades

(source: ers.usda.gov/data-products/… )

This chart confirms that most of the growth indeed did *not* come from using more land. In addition, it tells an interesting story about what caused growth instead...

From roughly 1960 to 1990, most of the growth was driven by greater use of inputs (e.g. fertilizers, irrigation, pesticides, etc., but also machinery)

However, around 1990, this pattern changed! It appears that most of the growth in recent decades is actually caused by efficiency gains ("improvements in total factor productivity" in the jargon)

The USDA estimate of efficiency gains accounts for labor used in agriculture, which has gone down too, but it's still the case that growth of many other inputs such as fertilizers has been slower than overall food production growth

Here's global fertilizer production, for example: grew 5x between 1960 and the late 1980s, but growth has been much more muted since (while food production kept growing)

In the US, for example, nitrogen use in maize production has been more or less flat since the 1980s, but yields have continued to grow (data from USDA)

Animal agriculture has seen big productivity gains too. Research by @bovidiva and others has shown that since the 1940s, the number of cows in the US fell by 2/3rds, yet US milk production *increased* by more than 60%

Basically, milk yield per cow increased about 5x. As a result, the sector produces a lot more milk than in the past, yet emissions (GHG, nitrogen, phosphorus) are way lower.

The interesting thing is that total feed use has decreased too, roughly in line with the decrease in the number of cows. So the main story is really: doing more with less

There are many factors here. A big part of the story is better breeds (Holstein instead of Jerseys), better breeding (artificial insemination - the original AI!), but also better feed.

Even the grass has improved!

(See here for the paper: doi.org/10.2527/jas.20… - @bovidiva and colleagues also have a paper showing similar trends in more recent years)

Obviously, not all sectors in all countries can show these kinds of results. But the point is that we're not forced to choose between "using more land" or "using more inputs". There's a third option: "using resources more efficiently"

That's great news, because option 1 and 2 have many downsides. Option 3 holds the promise of feeding the planet without destroying it.

It's also great news because it allows for more in-depth discussions about which kinds of practices and policies can actually get us there, rather than the old debates about extensive vs intensive.

There are a few caveats though. First, "efficiency" is usually defined in terms of resources which have a market price.

It doesn't *automatically* mean we're achieving better environmental outcomes… although I'd argue it gives us a much better shot than the alternatives of relying on more land or more inputs

For example, efficiency gains mean that we can produce more outputs with fewer inputs, but that doesn't necessarily mean we will end up using fewer inputs, if we instead decide to consume way more outputs

Also, because the universe hates us, anything related to food systems is always more complicated than it seems, a general law which also holds true in this particular case

For example, imagine we manage to raise yields in Sub-Saharan African agriculture. SSA has long lagged behind the rest of the world and basically missed the trend of strong yield growth

"Raising yields" by definition means "more food per unit of land" so you might assume raising yields in SSA would mean we're saving land. BUT: it also means making farming more profitable in SSA, which could expand farmland there

You could even have a situation where farming "migrates" from other places with higher yields towards SSA where yields are now a bit higher, but still pretty low

The net result could be *more* land use rather than less! So, efficiency gains do not automatically guarantee sustainability. We also need conservation policies etc.

(More on that in this fascinating paper by @hertel_thomas @Nramankutty and Uris Baldos: pnas.org/content/111/38… )

The question of whether efficiency growth has been land-saving over the last few decades has been studied by @nvilloria

"We find that, in most countries of the world, growth in total factor productivity (TFP) [that is, efficiency gains] is either uncorrelated or is positively associated with cropland expansion…"

BUT: "… worldwide TFP growth have been an important source of global land savings." - WAIT BUT HOW

"The divergence between the country-level and the global results is explained by the changes in production patterns as countries interact in international markets." (doi.org/10.1093/ajae/a…)

As I said, things are always just a tad more complicated than we'd like. Bottom line: historically, efficiency gains were globally land saving, but they might not be if Sub-Saharan Africa saw a Green Revolution, unless other policies are in place

The key takeaway is that efficiency gains create the *potential* to use fewer resources but we shouldn't take that outcome for granted: we need to make sure we use that dividend wisely (which requires additional policies)

Now that I'm busy blurring my messaging, let's keep going: some places around the world should probably use *more* inputs! (E.g. in SSA, where input use is generally low)

But many other places are clearly not using resources efficiently at the moment, creating room for important efficiency (and environmental) gains

For example, it turns out globally crops only absorb about 35% of the nitrogen applied to them. Yes, we may be wasting ALMOST TWO-THIRDS of all nitrogen applied to crops! science.org/doi/10.1126/sc…

This is, to use the technical term, "bonkers"

On the other hand, in a weird way this is also good news, because it suggests there should be plenty of low-hanging fruit: we can probably cut nitrogen pollution considerably without hurting crop yields (efficiency gains!)

Here's another example hinting at how much room for improvement there is. The EU and India produce roughly the same volume of milk, but India has seven times (!) as many animals. (Data is from the OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook database; axes are in logarithms)

Let that sink in for a moment - think about what this means for e.g. GHG emissions...

EU cows have much higher milk yields - this partly reflects more inputs (e.g. feed) but also to a large extent is due to genetics: better breeds, better selection etc. Even closing the gap just a little bit would create big improvements

Plant and animal breeding (both using conventional and more cutting edge methods) hold tremendous potential, and so does innovation in many other areas (precision farming etc)

To unlock that potential we'll need to step up investments in agricultural R&D and extension, and generally in building a strong agricultural knowledge and innovation system

Research shows that investments in agricultural R&D yield very large returns - often 10 dollars of benefits for every dollar invested ucanr.edu/news/?routeNam…

Or in other words, we've been massively under-investing in ag R&D!

But we can (and should) also think about "efficiency" of the food system in broader terms. For example, we could define outputs as "healthy and sustainable diets" rather than just using the status quo of whatever diets we're currently eating

From that perspective, reducing food loss and waste and shifting diets towards healthier and more sustainable choices would also improve efficiency - i.e. achieving our nutrition objectives while using fewer inputs

For example, a massive amount of agricultural land is used for ruminant livestock (beef, sheep), and these also have the highest emissions intensities.

So even shifting away from beef and sheep meat to e.g. poultry would mean big improvements in environmental sustainability

I personally think this "efficiency" lens is a much better framing than the old "extensive versus intensive" way of looking at things. It allows us to ask more fine-grained questions, and come up with more context-specific answers

This reflects a broader theme of our @OECDAgriculture report "Making Better Policies for Food Systems" - things are rarely as black or white as they are portrayed in #foodsystems debates dx.doi.org/10.1787/ddfba4…

For example, some people like to say food systems are "broken" - but that overlooks spectacular achievements like massively increasing global food production to feed a growing population

Other people like to emphasize the need to produce more food above all else, which could easily lead us to overlook the massive environmental, nutritional and social challenges of food systems

Frankly, we can't afford these kinds of simplifications.

Food systems are complex and we need to come to grips with that complexity, and be pragmatic in thinking about solutions. But that's easier said than done, for at least two reasons:

First, food systems differ enormously from place to place, and are full of interaction effects (synergies and trade-offs); it's not easy to keep track of all these moving parts

Second (and this may surprise you), people often tend to disagree about what needs to happen to fix #foodsystems. This could be because of disagreements over facts, over interests, or over values.

When we started preparing our report on what policymakers should do to improve #foodsystems, we realized it would be impossible to provide an exhaustive view of *what* exactly should be done - but we could say something about *how* to make better policies

So, the question becomes: what are some general principles and good practices you can use to make policies that take into account local context, spillover effects, and inevitable disagreements?

In line with the two sources of difficulties mentioned earlier, we can break this down into two parts. One is the question of how to create "coherent" policies - taking into account the spillovers (synergies and tradeoffs)

The other part is how to manage disagreements over facts, interests, and values

Let's start with "policy coherence", which means: making sure your policy initiative to improve Outcome A doesn't accidentally backfire by making things worse on Outcome B

If you're a naive economist like me, this may initially not seem like much of a problem: why can't governments just "figure it out"?

Which is why it was good to be straightened out by colleagues @OECDgov as well as @JeroenCandel, @thefoodrules and @CorinnaHawkes, who have been thinking hard about what it takes to achieve policy coherence (in #foodsystems and elsewhere)

Governments have complex internal divisions of labor - across ministries/agencies, levels of gov't... Combine this with the intrinsic complexity of food systems and it's hard to even figure out who exactly is involved in making food systems policy

For example, here's @thefoodrules' overview of all the different gov't actors involved in food policy in England alone... kellyparsons.co.uk/who-makes-food…

Our own thinking on policy coherence is that in a complex world, we should try to make things "as simple as possible, but not any simpler". A few guidelines can help.

First, when making #foodsystems policy, we should be aware of possible synergies and trade-offs. That sounds super-trivial, until you realize that policies were historically made in silos, with little interaction between e.g. agriculture and public health agencies

But just being "aware" of possible synergies or trade-offs is not enough to build coherent policies. We also need to rigorously check whether these are *real*, or if real, whether they are big enough to matter for policy design

For example, many people seem to think that farm subsidies are contributing to obesity in the rich world, so it is often assumed that reforming farm subsidies could also help with fighting obesity. It turns out this is not how things work

As I explain in this thread, "farm subsidies" are actually often things like import tariffs which make food *more* expensive.

https://twitter.com/DeconinckKoen/status/1437343199530471424?s=20

Research shows that ag policies are "largely irrelevant" to obesity in rich countries annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.114…

So this is one example where a potential synergy turns out not to be very important. Always verify whether synergies and trade-offs are real!

Third on the list: remember that synergies and trade-offs depend on the specific policy instrument. Here's an example. Imagine you use a fertilizer subsidy to support farmers. As a result, farmers use more fertilizer, which is bad for the environment. So...

... in this particular case there is a trade-off between helping farmers, and helping the environment. But you could imagine paying farmers for eco-system services instead, turning this into a synergy. So it depends on the specific policy instrument!

Fourth idea: beware of silver bullets. Even when there are synergies, one initiative will rarely solve *all* your problems. We need to think in terms of policy mixes instead. @waiterich

Fifth idea: even if you make a smart choice of policy instruments, some trade-offs are inevitable. And here, the next step is *not* just a technical question. It involves a societal choice.

Obviously, you'll want the best possible analysis to clarify those choices. But in the end, different societies may end up choosing differently. The question is: how do societies make those choices?

We'll come back to that when we talk about disagreements on facts, interests, and values

(In case you missed it, the discussion on facts, interests, and values is in a separate thread ⬇️)

https://twitter.com/DeconinckKoen/status/1440301082048036872?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh