The name Kāśyapa corresponds to what we find in the Pāli Alambusā Jātaka (where the son Isisiṅga is called Kassapa, and he calls his father ‘Kassapa’) and in the Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya,

but particularly to the Vedic, Epic and Purāṇic tradition, where the protagonist of this story, Ṛśyaśṛṅga or Ṛṣyaśṛṅga, is regularly connected with the Kāśyapa Gotra (Lüders 1940: 1; Keith and Macdonell 1912, I: 118)

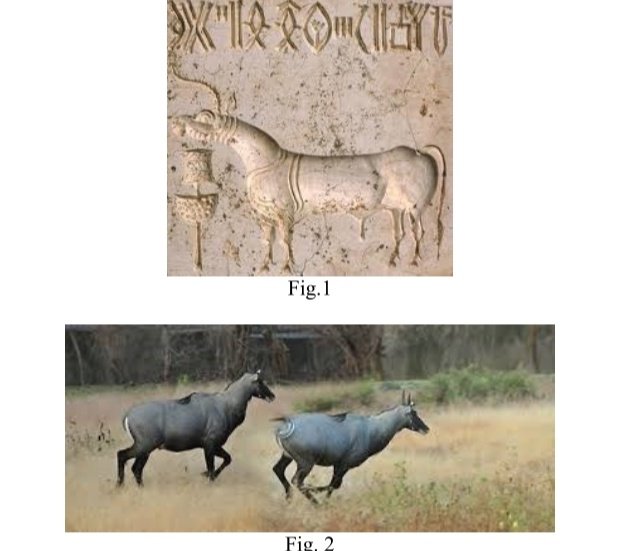

Ṛśyaśṛṅga/Ekaśṛṅga (a name meaning ‘(having the horn of the nilgai male antelope’) is born from a female deer or antelope (mṛgī), and has often animal features like one or two horns, and hoofs.

Ṛśyaśrṅga is connected with fertility and fecundity: in the epic versions of his story, he is searched for getting rain and sons. Monier-Williams reports in his dictionary about the word śṛṅga that it is also the name of a Muni “of whom, in some parts of India on occasion

of drought, earthen images are said to be made and worshipped for rain” (Monier-Williams : 1087). In the Kullu valley of Himachal Pradesh, in case of drought the other deities of the valley are brought to visit and pay homage to ‘Shringi Rishi’ to ask for rain,

and prayers to ‘Rushi Shrunga’ for rain, are made in Ganjam district in Orissa, on the hill where the saint is believed to live.

We can also see in this figure originally a mythical animal connected with rain, like the unicorn of the Bundahišn (19.1-12, cp. Yasna 42.4, West 1880: 67-69; Panaino 2001: 162-173; Parpola 2012: 131-133), who is a gigantic three-legged ass with one horn living in the world-ocean

helping Tištrya (the star Sirius), the deity of rain, to take the water from the cosmic sea Vourukaša, purifying the water by urinating in it, and making pregnant by his cry all good creatures.

It is interesting that in the version of the Mahābhārata and Padma Purāṇa Vibhāṇḍaka Kāśyapa( father Rsyasrnga) lives near a great lake, where his seed falls while bathing and later it fecundates the animal.

In Russian folklore, there is a one-horned beast, mother or father of all beasts, living on the holy mountain, called Indra, Indrik, Vyndrik or Edinrog (‘unicorn’)

[Fig below], who delivers the world from drought by going under the earth and releasing the waters,

[Fig below], who delivers the world from drought by going under the earth and releasing the waters,

and also purifies them (Russell 2009:

177-185). The use of the name Indra for a being that releases the waters like the Vedic god is interesting, however this myth can be influenced by the Siberian myth of the unicorn-mammoth:

177-185). The use of the name Indra for a being that releases the waters like the Vedic god is interesting, however this myth can be influenced by the Siberian myth of the unicorn-mammoth:

the tusk of the mammoth often found in Siberia is interpreted by the local populations as a horn, belonging to a subterranean or aquatic beast with one horn, creating rivers and lakes (Janhunen 2012: 198-200).

We can also suppose that the mammoth tusks were widely known in Asia, and spread the mythology of the unicorn. Another prehistoric animal that may have influenced the mythology of the unicorn is the Elasmotherium, a sort of massive

rhinoceros with one long horn that lived also in Russia, Caucasus and Central Asia until at least 10000 years ago. But also in historical times, the 10th-century Arab traveler Ibn Fadlan spoke, in his report of the expedition among the Volga Bulgars, of a one-horned

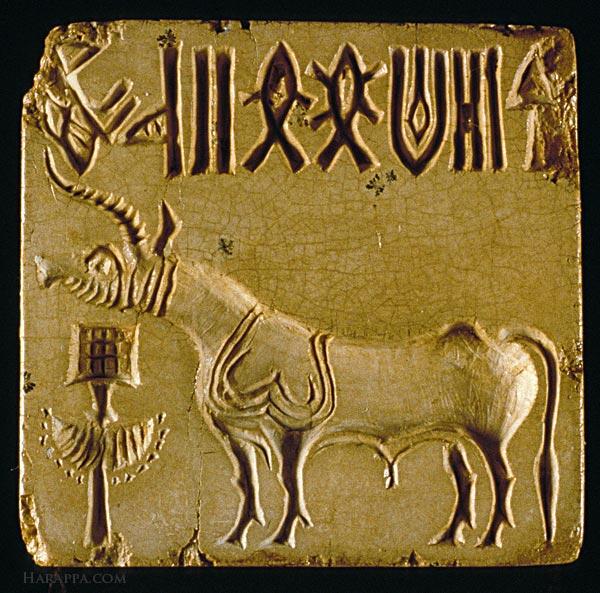

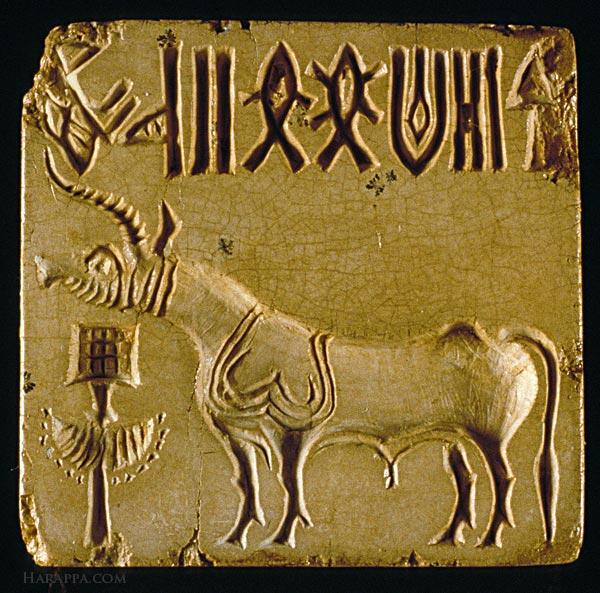

living in the forests on the Volga river, which seems to correspond to an Elasmotherium (Walker 2012: 7-8). An analogous mythical animal can be represented on the Harappan seals(Fig below), where the most common image is a unicorn, reproduced also in some clay figurines.

It has the form resembling a bull but with a long neck (often with some lines like wrinkles), a peculiar design on the shoulder, similar to a peepal leaf, an antelope-like head, and one long horn on the forehead

Apparently it reproduces a nilgai, the ‘blue bull’ antelope, which is still considered a sacred animal because it is identified as the same as the cow (as the name nilgai itself shows), has often wrinkles on

the neck, and the skin on the shoulder can create folds composing a shape similar to that found on the unicorn of the seals

Only the long horn is remarkably different from the short horns of the nilgai (however, they too curve forward), but this can be a sign intended to show that it is not a normal nilgai but a unicorn nilgai.

The Sanskrit name of the male of this antelope was ṛśa or ṛśya in Vedic texts and more often ṛṣya later on. Ṛśyaśṛṅga/Ṛṣyaśṛṅga, then, could be an anthropomorphous representation of this sacred animal, connected with water and fecundity

In RV VIII.4.10 Indra is invited to come to drink Soma like a thirsty nilgai, and after that he is represented as ‘urinating it (the Soma) down’, a symbol of rain

Parpola 2012: 133, remarks about the Zoroastrian mythical Ass: “James Darmesteter has assumed that the Three-legged Ass is a celestial animal, whose urine is rain possessed with the power to kill demons. Darmesteter points out that this mythical animal of Iran thus corresponds to

the heavenly bull, which many peoples have imagined as urinating rain.”

In Atharva Ved IV.4, a charm to restore virile power, we have the phrase ārśa vṛṣṇya for indicating the virile power, then the invitation to approach the woman like the nilgai bull his female.

According to PB V.4.13-14, during the description of the Mahāvrata (a ritual with clear connections with fertility and water), the ṛśyasya sāman (‘melody of the nilgai bull’) is recited

Then a myth is given where all beings praised the different members of Indra, but only the ṛśya praised one member, which the commentator identifies with the sexual organ (Caland 1931: 77 f.; Parpola 2012: 138 Thus, this animal is related again not only to the generative faculty

but also to the god Indra

Another interesting Vedic tradition about the ṛśya is the astral myth found in the Aitareya Brāhmaṇa, where Prajāpati, desiring his daughter (identified either with Heaven, div, or with the Dawn, uṣas)

Another interesting Vedic tradition about the ṛśya is the astral myth found in the Aitareya Brāhmaṇa, where Prajāpati, desiring his daughter (identified either with Heaven, div, or with the Dawn, uṣas)

took the form of a nilgai bull (ṛśya), while the daughter that of its reddish female (rohit), and approached her. The gods, in order to punish or stop him, created a divine being who pierced the antelope with an arrow, and so Prajāpati became the constellation called mṛga

According to archeologist Dr S R Rao that the unicorn itself might be a composite animal in which horse was embedded. Actually what S R Rao proposed was a very plausible scenario in which ‘gradually the animal deities were absorbed in the Fire-God......

wherein the unicorn, itself a composite figure of horse and other animals, represented the Fire-God.’

Dawn and devolution of the Indus civilization', 1991) Gautama Vajra Vajracharya, a Nepali Sanskritist, in a 2010 paper titled 'Unicorns in Ancient India and Vedic Ritual',

published in EJVS a journal edited by rabid pro-invasionist/migrationist Michael Witzel, drew attention to this aspect - that 'the neck of this (Harappan) unicorn is much more elongated than that of a bull and bears some similarity to that of a horse or an ass.'

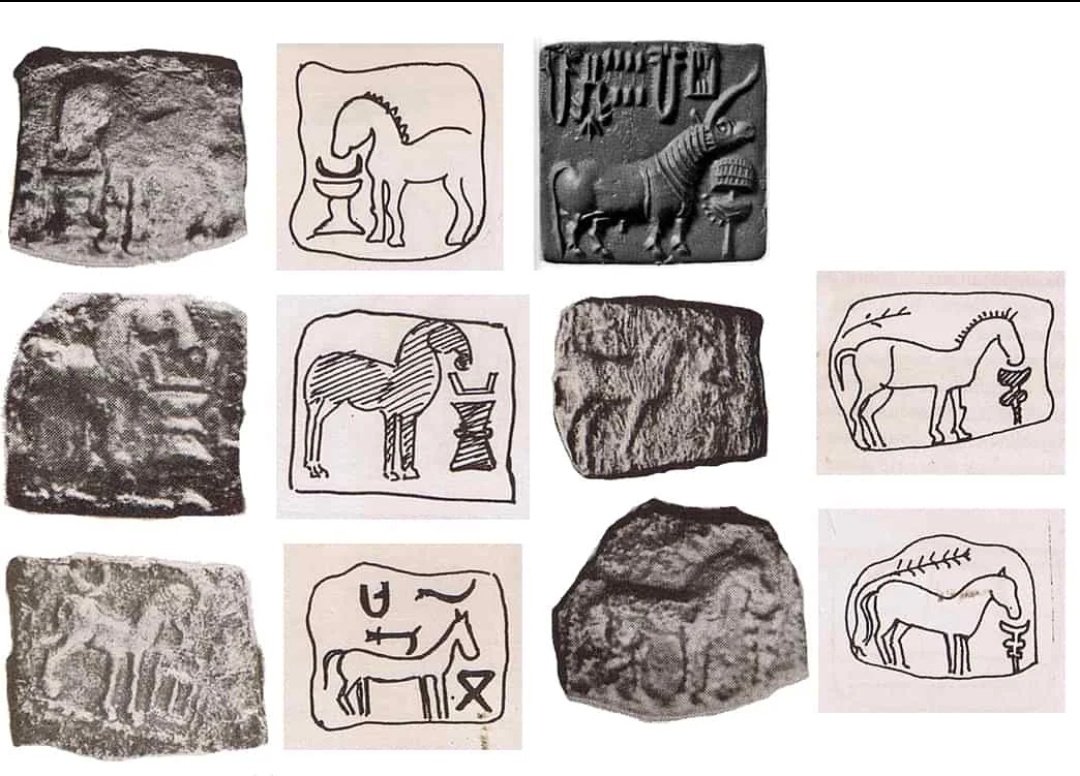

In 1935, historian Charles Louis Fabri published a paper arguing for the continuity of Harappan civilisation to the later historical times through the study of imagery in the punch-marked coins with those in the Harappan seals.

What 'immediately struck' him were 'certain animal representations' which were 'the humped Indian bull, the elephant, the tiger, the crocodile, and the hare'. He observed that the 'old tradition was kept alive up to proto-historic times'

though the punch- marked coins even though they are separated from the Harappan seals by a very minimum period of thousand years.

Interestingly, in his comparison of seals and punch-marked coins, Fabri did not compare horse representation in punched mark coins with Harappan seals. Instead he had drawn a parallel between bull and the unicorn

A comparison of the representation of the horse in punch-marked coins and the unicorn however reveals a very remarkable similarity

What actually seems to connect the horse depiction in punch-marked coins and the Harappan unicorn seal is the remarkable similarity between the object shown before the unicorn (Harappan seal) and before the horse (punch-marked coins).

The ‘cult object’ before the Harappan unicorn and the object placed before the horse in the punch-marked coins indicate the composite nature of unicorn which includes the horse.

Indologist Irvatham Mahadevan, who incidentally believes that Harappan culture was linguistically Dravidian and culturally Vedic, connects the so-called 'cult object' before the unicorn to the Soma ritual

In his interview to ‘Harappa.com’ he explains: "According to me, the cult object is made of three parts, an upper cylindrical vessel, a lower cylindrical vessel with holes like a colander for example, and the whole thing is stuck on a staff.

... Since we know that the unicorn seals were the most popular ones, and every unicorn has this cult object before it, whatever it represents must be part of the central religious ritual of the Harappan religion. ...

I am familiar with the RgVeda, and as I was looking at the zig zag lines flowing across the filter showing the filtering ritual and the coming out of the drops,

I was remindd of the two most powerful imges in the soma chaptr of the RV, Pavamana and Indu. Pavamana literally means the flowing one, the soma, as it flows down, and Indu are the drops which collct at the bottom of the filter. So I found that this could hardly be a coincidence"

Although Iravatham Mahadevan contends that the Indo-Aryans learnt the Soma ritual from the Harappans as the Soma ritual is not present in the so-called ‘Indo-European’ cultures in the West.

Now this hypothesis is totally baseless, All of we know soma cult in other IE cultures

Now this hypothesis is totally baseless, All of we know soma cult in other IE cultures

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh