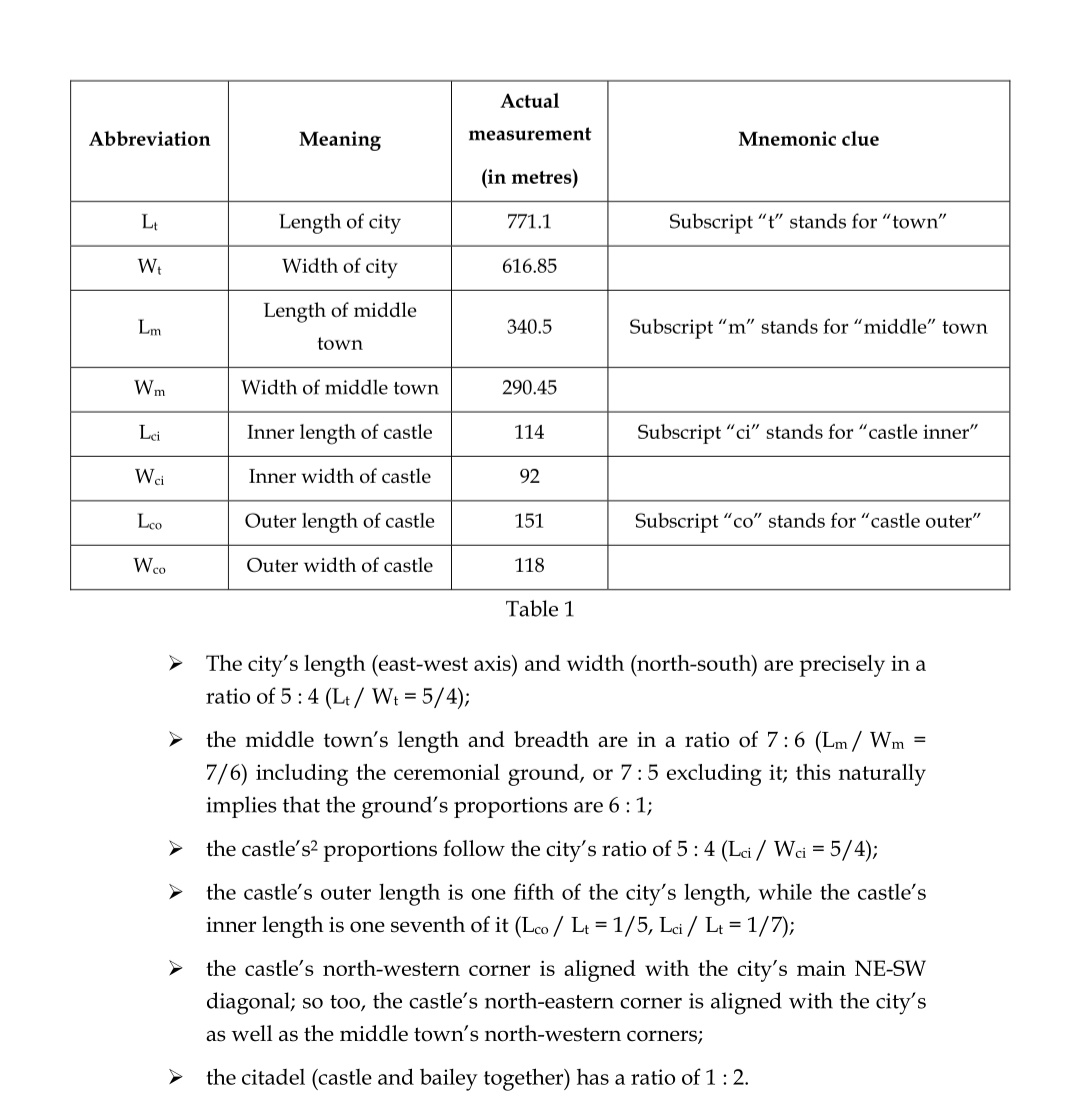

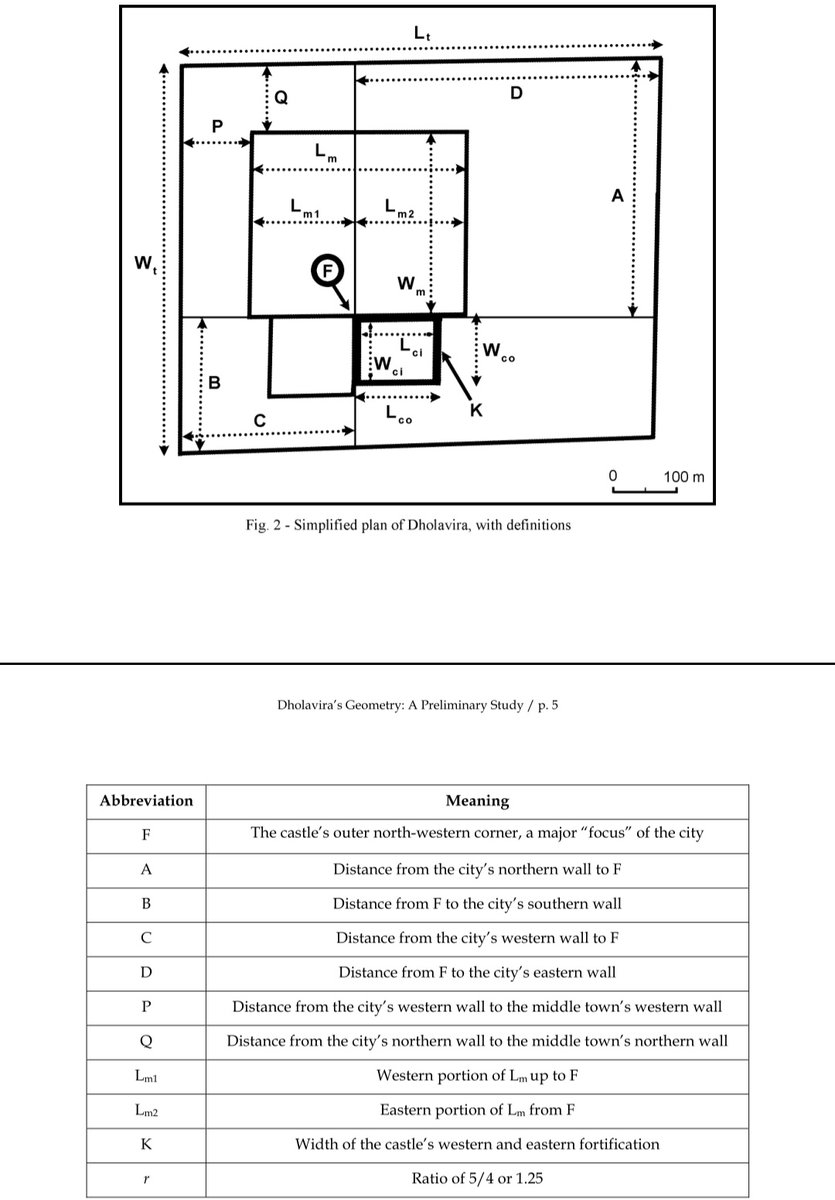

The basic ratios adopted in Dholavira’s plan, r = 5/4 or 1.25 (for the castle, the town, and a few other internal proportions) and 7/6 (for the middle town), must have held a special significance in the Harappan mind, most likely an auspicious one. Indeed, it is quite remarkable

that these same ratios are commonly prescribed as auspicious proportions for houses in various traditions of Vastu Shilpa.

Varahamihira, for instance, writes in chapter 53 of his Brihat Samhita: “The length of a king’s palace is greater than the breadth by a quarter.... The length of the house of a commander-in-chief exceeds the width by a sixth.”

These two ratios (1 + 1/4 and 1 + 1/6) are better expressed as 5/4 and 7/6 — very precisely Dholavira’s basic proportions! This seems too much of a coincidence:

while Vastu Shastra as codified in Varahamihira’s time (or possibly earlier) was clearly not in existence during the mature Harappan phase, it is wholly possible that specific proportions regarded as auspicious in Harappan times were

carefully preserved and later integrated in a systematic approach to architecture.

It may be objected that Dholavira’s architects preceded Varahamihira by some three millennia; if a tradition of auspicious ratios was thus preserved, should we not have some trace of it in between?

It may be objected that Dholavira’s architects preceded Varahamihira by some three millennia; if a tradition of auspicious ratios was thus preserved, should we not have some trace of it in between?

Indeed we do: the Shulba Sutras provide one such missing link. For instance, Baudhayana’s Shulba Sutra (4.3) lists detailed dimensions for the trapezium-shaped sacrificial ground (mahavedi),where the sacred fire altars are to be arranged

its longer (western) side must measure 30 prakramas (a unit roughly equal to 54 cm) while its shorter (eastern) side will be 24 prakramas — exactly our ratio r = 5/4. We find r again embedded in Baudhayana’s system of units (spelt out in 1.3):

for instance it is the ratio between the pada (= 15 angulas) and the pradesha (= 12 angulas), and between the purusa (5 aratnis) and the vyayama (4 aratnis). More research is likely to bring out similar examples from the Brahmanas and the Puranas.

In the meantime, is it not fascinating that proportions deliberately adopted at Dholavira and Lothal should have such a central importance in the Shulba Sutras as well as Vastu Vidya?

In itself, the preservation of ratios and units right from Harappan times is nothing to be surprised at: it has long been noted that Harappan units of lengths and weight resurfaced in historical times, and there has been a steadily mounting body of evidence.

the proportions mentioned in the Shulba Sutras for the mahavedi (the main sacrificial ground) appear earlier in the Shatapatha Brahmana (I.1.2.23, quoted in The Sulbasutras, ed. S. N. Sen & A. K. Bag, New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy, 1983, p. 170); in this ancient text

instead of specific units as in the Shulba Sutras, steps are used: the vedi’s western side is 30 steps long, while the eastern side is 24 steps. The result is however the same in terms of proportions — 5 : 4, our Dholavira ratio.

This is one more link in the long transmission from Dholavira’s architects to the codifiers of Vastu Shastra, but also one more connection between the Harappan and the Vedic worlds.

One system of units described in Kautilya’s Arthashastra (usually dated a few centuries BC) seems to fit very well in the Dholavirian schme. In a section on measures of space and time (2.20.19, see R. P. Kangle’s translation, New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1986, part II, p. 139)

we are told that “108 angulas make a dhanus, measure for roads and city-walls....” The actual measure of an angula, related to the width of a finger, has probably varied in time and space, as have most other units; common estimates include 17.78 mm,and three-fourths of an inch or

and three-fourths of an inch or 19 mm (J. R. Fleet), among others.

With such a value, a dhanus or 108 angulas as defined by Kautilya would be about 1.91 m. Since we noted that K is close to 10800 Lothal units, this leads to K = 1080 angulas = 10 dhanus.

With such a value, a dhanus or 108 angulas as defined by Kautilya would be about 1.91 m. Since we noted that K is close to 10800 Lothal units, this leads to K = 1080 angulas = 10 dhanus.

This certainly looks like a convenient number, all the more striking as Kautilya states that the dhanus is to be used as a “measure for roads and city-walls.”

In a confirmation that this is not just wishful thinking or a happy coincidence, we find that we can easily express the city’s other main dimensions in terms of the dhanus: following our earlier formulas, the castle’s inner length (Lci / K = 6) becomes 60 dhanus (just like the

southern side of Lothal’s “acropolis,” incidentally) while its inner width is 48 dhanus; the castle’s outer length (Lco / K = 8) and width become 80 and 64 dhanus respectively

the middle town’s length (Lm = 3 Lci) is now 180 dhanus, while the city’s overall length (Lt / Lm = 9/4) and width are 405 and 324 dhanus. All these numbers are within 1% of actual figures.

Such a system, based on a “master unit” equal to 108 times the basic Lothal unit multiplied by 10, appears to be the key to Dholavira’s metrology, and clearly survived the collapse of Harappan urbanism, probably because such units remained in use for sacred or ritual purposes

Such as fire altars.

Further verifications with dimensions of streets, large buildings etc. are certainly called for (keeping in mind however that different units can be used for different purposes), as is a systematic study of dimensions and proportions in major towns and

Further verifications with dimensions of streets, large buildings etc. are certainly called for (keeping in mind however that different units can be used for different purposes), as is a systematic study of dimensions and proportions in major towns and

and cities of the Indus-Sarasvati civilization, and their transmission to the historical period.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh