That first day as the Head of Engineering at a fast-growing startup is always glorious.

Not an engineering manager anymore, but a Head Of. The non-technical-at-all founder hired them because they *really* needed someone to get sort the eng problems.

A new story starts today:

Not an engineering manager anymore, but a Head Of. The non-technical-at-all founder hired them because they *really* needed someone to get sort the eng problems.

A new story starts today:

The first week is done, and it's exciting. Well, a bit annoying as well. The founder keeps checking in, and talking about how they see this role, and what they want the EM (not Head of Eng) to do.

Problem is, much of it is not how the EM worked in the past, and it doesn't work.

Problem is, much of it is not how the EM worked in the past, and it doesn't work.

Like the obsession the founder has with what are essentially micromanagement practices.

"This is how we work. High autonomy+high accountability is our culture". But then eng is told the work they should do, given deadlines with no input, and judged on "getting shit done".

"This is how we work. High autonomy+high accountability is our culture". But then eng is told the work they should do, given deadlines with no input, and judged on "getting shit done".

Anyway, the EM is now Head of Engineering, so they know they'll change this. Once they gain trust.

Which is getting harder, every week.

An outage happened yesterday, taking down the product for hours. The founder is furious and is publicly blaming the EM already.

Which is getting harder, every week.

An outage happened yesterday, taking down the product for hours. The founder is furious and is publicly blaming the EM already.

"Well, no one said Head of Engineering is easy" justifies the EM. Ok, so first, no more outages.

They announce all production pushes stop until the outage root cause is fixed. Engineers can't believe they finally get to fix things.

Neither can the founder. They summon the EM:

They announce all production pushes stop until the outage root cause is fixed. Engineers can't believe they finally get to fix things.

Neither can the founder. They summon the EM:

"Stopping shipping to production is ABSOLUTELY out of the question. And don't you pull something like this in public without checking with me again. I hired you to fix engineering, not to make things worse."

The EM tries to explain but gets shot down.

This is not looking good.

The EM tries to explain but gets shot down.

This is not looking good.

A direct message on LinkedIn from the previous Head of Engineering. "Want to hear some advice?" it reads.

They meet up, the Current and Former.

"Look for a new gig, I'm telling you. I wish someone told me what I told you 12 months ago." the Former concludes after the catchup.

They meet up, the Current and Former.

"Look for a new gig, I'm telling you. I wish someone told me what I told you 12 months ago." the Former concludes after the catchup.

The EM is not giving up on the Head of Engineering role though.

The next months are hell.

Hands tied, their role is relegated to carrying out whatever the founder approves of. When hiring, they feel like a fraud, describing the culture of the old place, not the current one.

The next months are hell.

Hands tied, their role is relegated to carrying out whatever the founder approves of. When hiring, they feel like a fraud, describing the culture of the old place, not the current one.

After six months, going to work fills them with dread.

The founder is getting more unhappy is a reason for it.

On the first performance review, the rating is "below". "Since I hired you, we had two massive outages and work is still slow. You have one more chance. Do better."

The founder is getting more unhappy is a reason for it.

On the first performance review, the rating is "below". "Since I hired you, we had two massive outages and work is still slow. You have one more chance. Do better."

The decision to quit when an engineer shares they're leaving to their former company, taking a cut in title, from Principal to Senior.

"It's the dev culture. No offense, but I hoped you coming would make it better. I feel like a second-class citizen here. I don't want this."

"It's the dev culture. No offense, but I hoped you coming would make it better. I feel like a second-class citizen here. I don't want this."

This is when they realize that the founder will not change.

No matter what they tried, it got shot down when it went against ideas the founder had on engineering. They'll never succeed here.

Months later they accept an EM position at a larger company, with double the paycheck.

No matter what they tried, it got shot down when it went against ideas the founder had on engineering. They'll never succeed here.

Months later they accept an EM position at a larger company, with double the paycheck.

The founder is not surprised when the EM resigns and goes on to repost the exact same job description from 8 months before. The EM wonders if they should also message the next Head of Engineering.

They leave. The Head of Engineering is back to being an EM, but is happier for it.

They leave. The Head of Engineering is back to being an EM, but is happier for it.

And the new job is *great*. The EM is on a highly performing team, working with great people. Two years alter, one of their products gets lots of press, the EM being featured in the article.

A flurry of congratulations and private messages follow. One of these stand out.

A flurry of congratulations and private messages follow. One of these stand out.

It's a message from a startup founder who just raised $17M. A coffee follows, where the founder offers the role of heading up the eng team to the EM on the spot. They need someone technical.

The EM hesitates, but just for a second. This will be different.

The EM hesitates, but just for a second. This will be different.

https://twitter.com/GergelyOrosz/status/1443165035400990725

Within minutes, multiple Head of Eng’s messaged how this was all too real for where they are at… which is, on one end, funny, and sad, on the other.

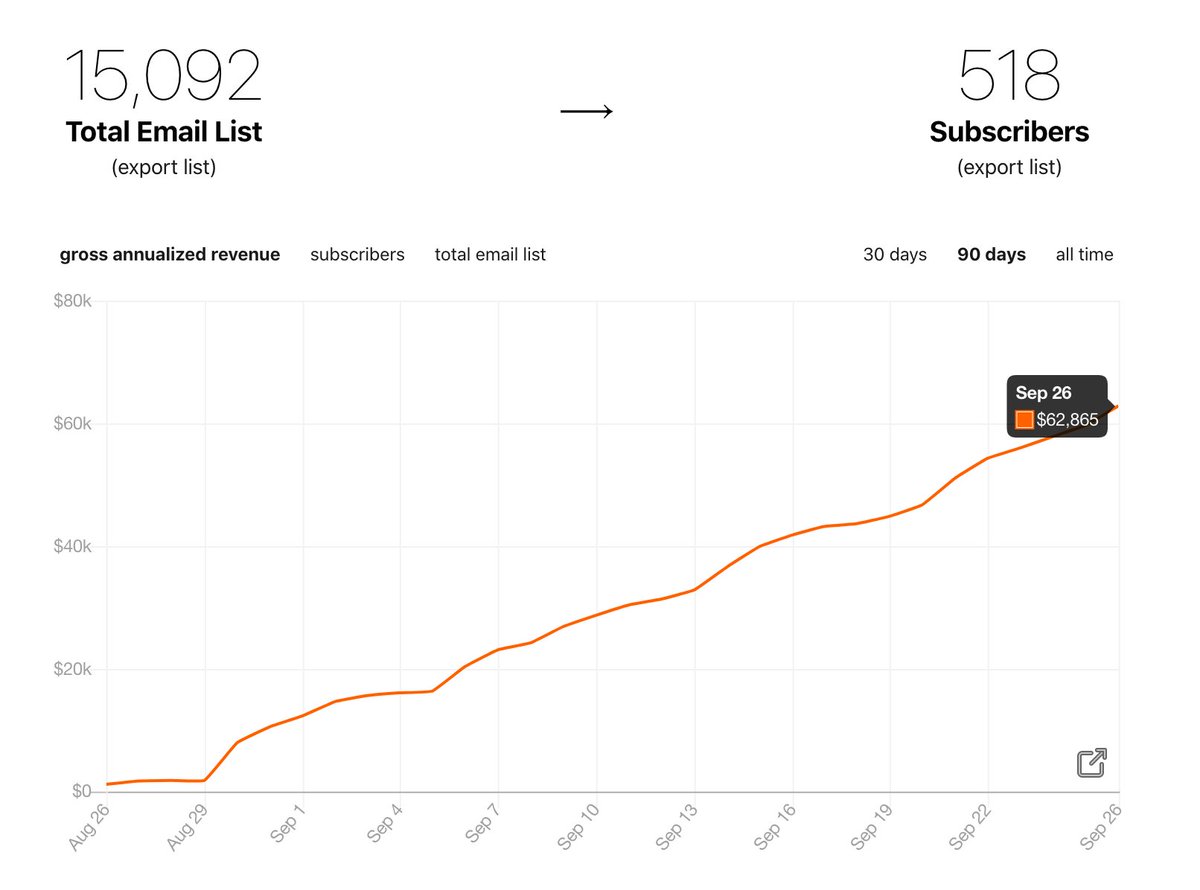

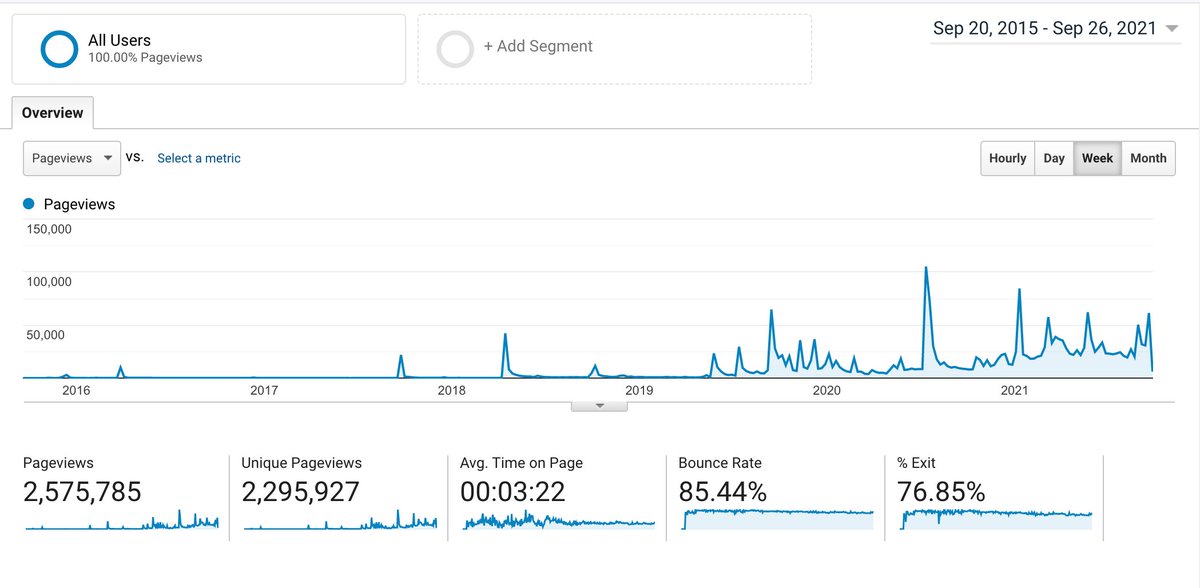

Unsure if I’ll cover this specific topic at newsletter.pragmaticengineer.com but working with non-technical stakeholders will be one.

Unsure if I’ll cover this specific topic at newsletter.pragmaticengineer.com but working with non-technical stakeholders will be one.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh