🥃🧵 Happy Oktoberfest!

Hey! Do you like Germany? 🇩🇪

Do you like beer? 🍺

Do you like German beer?

🇩🇪🍺

Yeah? Well then, THANK A SOCIALIST! Because without socialist temperance, German drinking culture would’ve been vastly different.

A short #LiquorThread 🥃🧵 1/

Hey! Do you like Germany? 🇩🇪

Do you like beer? 🍺

Do you like German beer?

🇩🇪🍺

Yeah? Well then, THANK A SOCIALIST! Because without socialist temperance, German drinking culture would’ve been vastly different.

A short #LiquorThread 🥃🧵 1/

First, check out this map of Europe’s dominant drinking cultures: wine (red), beer (brown) & spirits (blue). Makes sense: in southerly regions where grapes grow, you get wine. Otherwise: beer. The further northeast & colder the more liquor-y it gets. 2/

bigthink.com/strange-maps/4…

bigthink.com/strange-maps/4…

Even today, there’s a widespread “geographic determinism” myth of drinking cultures. Montesquieu even wrote about it in his “Spirit of Laws” (1748).

(But it’s based on the FALSE premise that liquor is a stimulant, rather than a depressant. Oops.)

SCIENCE! 3/

(But it’s based on the FALSE premise that liquor is a stimulant, rather than a depressant. Oops.)

SCIENCE! 3/

Anyway, look at that map again. The dividing line between beer culture & liquor culture looks a LOT like the 19th C. boundary between the German Empire & the Russian Empire.

Which is a POLITICAL boundary, not a geographic or climatological one.

What’s going on here?

4/

Which is a POLITICAL boundary, not a geographic or climatological one.

What’s going on here?

4/

Let’s rewind. Some 600 years ago, the only booze in Europe was fermented: wine (from grapes), mead (honey), beers & ales (grains), cider (fruit), kvas (bread), etc.

As products of a natural process, all were only mildly alcoholic, below 10%ABV 5/

As products of a natural process, all were only mildly alcoholic, below 10%ABV 5/

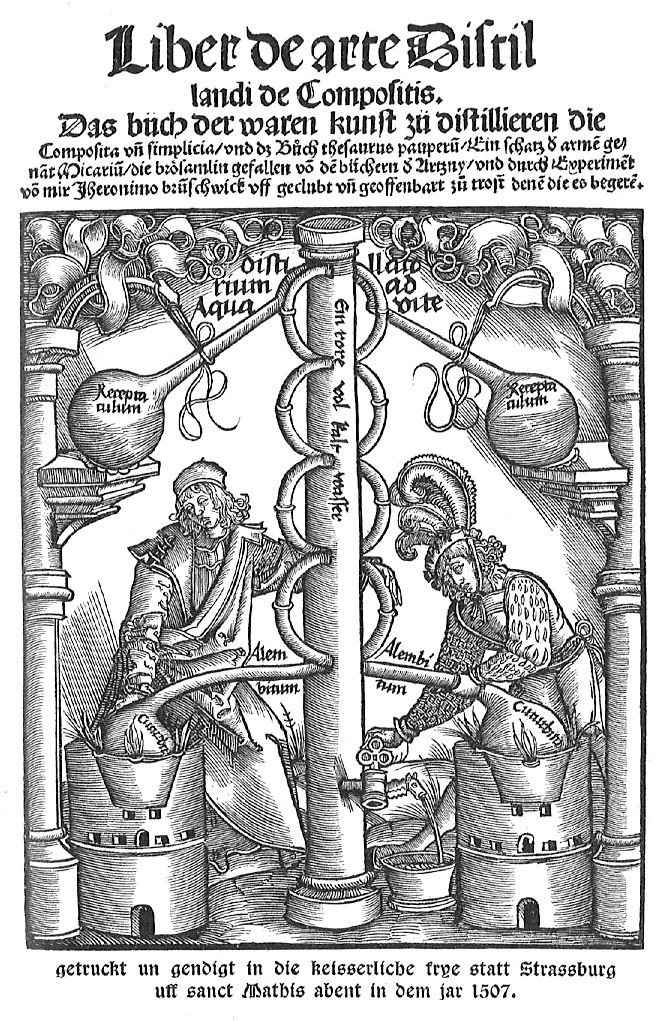

All of this changed radically about 500 years ago, as medieval alchemists rediscovered the Arabian science of distillation, to make a medicinal elixir known as “aqua vitae.” This distilled “water of life” became part of the alchemists’ arsenal of medical tinctures. 6/

If fermented beers & wines were like bows & arrows, distilled liquor was like a cannon: a new, industrial innovation with a potency unimaginable to traditional societies, that would revolutionize economics, politics, and culture. 7/

As the science spread across Europe, new distillates appeared w/ local characteristics: whiskey (British Isles), akvavit (Scandinavia), gin (Low Countries), vodka (Russia & Poland), raki (Mediterranean), rum (Caribbean), grappa (Italy), cognac (France), schnaps (Germany), etc. 8/

My 2014 Vodka Politics book argues that vodka took root in Russia not because of climate or genetics, but because the tsars had a monopoly on liquor sales: highly potent vodka was more profitable to the state than beers, wines, meads & kvas. 9/

amazon.com/Vodka-Politics…

amazon.com/Vodka-Politics…

That allure of tremendous profits & gvt revenues was a defining feature of alcohol politics across the empires of Europe—& even the US—in the 19th century. Imperial Germany was no exception. 10/

At that time, Germany wasn’t a single country, but a collection of 26 semi-sovereign states, duchies & kingdoms, dominated economically and politically by the arch-conservative Kingdom of Prussia (here in blue). 11/

By the 1800s, the political divisions were clear. Beer was the drink of the liberal cities. Before modern bottling, beer spoiled easily & couldn’t be transported far. Beer slaked the thirsty workers, who poured into Germany’s cities during the Industrial Revolution. 12/

Distilled liquor—in Germany, schnapps—was manufactured by the rural, conservative aristocracy: the JUNKERS of Prussia.

With a few pennies of grain, water & peasant labor, they could distill a lucrative, addictive substance that didn’t spoil & could be transported far. 13/

With a few pennies of grain, water & peasant labor, they could distill a lucrative, addictive substance that didn’t spoil & could be transported far. 13/

During the “Schnapps Revolution,” cheap Junker-made liquor flooded Germany. From 1806-1831, consumption of potent distillates TRIPLED. So did drunkenness, poverty, murders & arson. Germany was on its way to becoming a spirits-drinking nation, much like Russia to the east. 14/

“The drunkenness that had once cost three of four times as much was now readily available every day, even to the very poor,” wrote Friedrich Engels about the 1830s. (Yes, THAT Friedrich Engels.) “A man could stay drunk all week for just 15 silver groschens.” 15/

“The only industry that has produced more devastating effects is the Anglo-Indian opium trade for the poisoning of China,” Engels claimed, noting even that “was aimed against far-off strangers, not its own people.” The profit-for-poison dynamics were the same. 16/

The difference between beer & liquor was like day & night. The beerhalls of Bavaria and & industrialized cities of western Germany were bright, airy, rambunctious places for industrial workers to unwind, fraternize, bond, & even organize politically. 17/

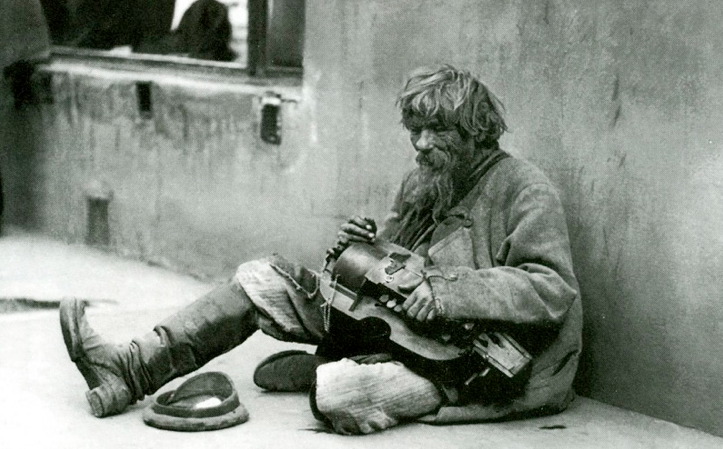

By contrast, the Schnapshölle, or schnapps hall, was a dank, secluded place where German paupers would stumble-in alone, with the sole intent of getting thoroughly drunk as quickly as possible, to forget their misery and poverty. 18/

Beer became the symbol of working-class strength and unity of purpose. Schnaps was scorned as the drink of the underclass, the “Lumpenproletariat,” whose misery & drunkenness only enriched the Junker aristocracy further. 19/

The avatar of conservative Junker aristocratic privilege was Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck. When the Panic of 1873 smashed the German economy, Bismarck doled-out hundreds of millions of Reichsmarks to the Junkers to keep their distilleries churning-out liquor. 20/

These corrupt subsidies were called “Liebesgabe,” or “gifts of love.” They shored-up Bismarck’s conservative base, infuriating the liberal & socialist opposition. Consequently, Bismarck outlawed the Social Democratic Party, & closed any beerhalls harboring socialist meetings. 21/

When a dinner guest once pointed out that there was liquor and wine on his table, but no beer, Bismarck snapped: Beer “makes you dumb, lazy, and impotent. It is the fault of all those democracy-blatherers who drink it.” Adding: “A good corn brandy would be preferable.” 22/

That distilled liquor made the rich richer & the poor poorer was obvious to Marxists from the beginning. It was capitalism at its most predatory. Consequently, generations of European socialists promoted temperance as a means of lifting up the working classes. 23/

By the 20th century, every socialist party in Europe had its own temperance policies. Swedish Social Democrats had a prohibition plank. The Finns and Norwegians required abstinence. British socialists—born of “teetotal Chartism”—focussed on retail-sales restrictions. 24/

And even Vladimir Lenin—who’d long railed against the tsar’s “drunken budget” and would continue Russia’s wartime prohibition post-1917—still enjoyed the occasional (workers’) beer while in his European exile. 25/

The socialist Second International declared: “Governments & Capitalists alike are interested in furthering the excessive use of alcohol” for profit... “The emancipation of the working classes from the yoke of alcohol must therefore be the task of the working classes alone.” 26/

The head of the Second International, Belgian socialist Emile Vandervelde explained: “there’s no real difference between the moderate use of fermented beer or wine and the complete abstinence from alcohol,” since it was cheap distilled liquor that was the problem. 27/

Socialists, he said, should lead by abstinent example: “Let us be tolerant, then for others, but let us be strict for ourselves,” so that the working class as a whole will learn and “grow in dignity and power, and escape the tyranny of alcohol.” 28/

In Germany, the socialist movement was led by influential Marxist philosopher Karl Kautsky, who penned a series of articles on the “Alkoholfrage” in his Die Neue Zeit newspaper. 29/

Kautsky explained that not only the TYPE of alcohol consumed had changed over the past hundred years—away from wholesome, German beer and toward rotgut schnapps—but “so has the way to drink changed as a result of the revolution in the conditions of production.” 30/

In 1909, the German Reich began a massive military buildup to challenge British naval superiority—which in five year’s time, would help ignite World War I. 31/

But to pay for such militarization, the German government decided to raise taxes... on BEER. German workers responded in the Bierkrieg—or Beer War—of 1909. Angry workers filled the streets of Frankfurt, Dortmund, Essen, Leipzig, Breslau and beyond. 32/

The Social Democrats announced a nationwide boycott of the junkers’ schnapps, to overwhelming approval. Vorwärts explained temperance struck at the heart of junker power, undermine gvt militarization & deliver “the proletariat’s liberation from chains of its own making." 33/

In the first five months of the Schnapsboykott, consumption of distilled spirits dropped by 31 percent, accelerating Germany’s transition from a predominantly spirits-drinking nation like Russia to a largely beer-drinking one, like Belgium. 34/

Indeed, in the fifty years before World War I, German beer consumption more than doubled, whereas consumption of schnapps and other German hard liquors was CUT IN HALF, largely thanks to the activism of Germany’s temperate social democrats. 35/

Today, beer seems an inseparable part of German national identity. But it wasn’t always that way. Nor was it always a foregone conclusion. 36/

So, if you find yourself celebrating Oktoberfest with friends & family in a festive, Munich-style Biergarten, rather than tossing back shots in a dingy, dimly lit Schnapshölle, raise a toast to the German temperance-socialists who made it all possible. 37/

If you found these perspectives provocative, may I suggest checking out my new book: Smashing the Liquor Machine: A Global History of Prohibitionism, which is available everywhere books are sold. Many thanks! 38/END

amazon.com/Smashing-Liquo…

amazon.com/Smashing-Liquo…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh