If you wear glasses – prescription, shades, even Facebook smart glasses – you’ve likely dealt with EssilorLuxottica.

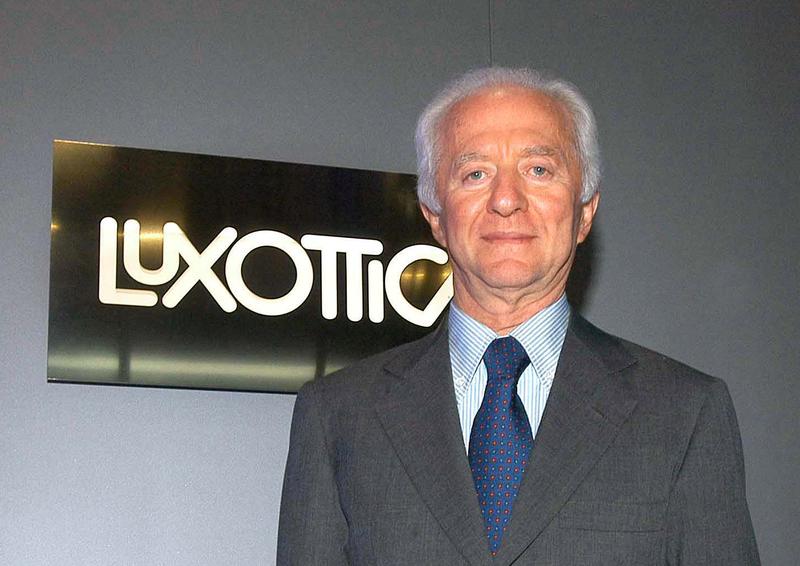

The conglomerate was built by Leonardo Del Vecchio who rose from penniless to being the 2nd richest Italian.

His story is master class in business strategy.

The conglomerate was built by Leonardo Del Vecchio who rose from penniless to being the 2nd richest Italian.

His story is master class in business strategy.

After the 2018 merger of Del Vecchio’s Luxottica with the French Essilor, the company dominates global eyewear with

-140,000 employees

-€14.4bn in 2020 revenue

-11,000 stores

Brands including Ray Ban, Oakley, Oliver Peoples, and partnerships from Armani to Prada.

-140,000 employees

-€14.4bn in 2020 revenue

-11,000 stores

Brands including Ray Ban, Oakley, Oliver Peoples, and partnerships from Armani to Prada.

Del Vecchio was born in Milan in 1935. His father died when he was only five months old and his mother was forced to send him to a local orphanage at age 7.

The boy became an apprentice at a tool factory and graduated in 1958 with a degree in metal engraving.

The boy became an apprentice at a tool factory and graduated in 1958 with a degree in metal engraving.

He set up his own workshop in Milan before moving to Agordo in 1961. The mountain town struggled and Vecchio was given space to build a factory. Two customers helped finance the launch of Luxottica as a contract manufacturer making parts and frames for others.

Del Vecchio was obsessed with improving and took courses in machine design to make his own equipment.

He lowered the cost of adapting to changes in fashion: "by mastering all the technologies, we [became] very competitive on price, without having to compromise our quality."

He lowered the cost of adapting to changes in fashion: "by mastering all the technologies, we [became] very competitive on price, without having to compromise our quality."

The company nearly failed in 1971, when his investors called in their loans. But he found capital from a distributor.

He also launched his own brand: “For ten years I sold parts. One day I say, 'I'm stupid. I'm sending parts to manufacturers. Why don't I industrialize this?”

He also launched his own brand: “For ten years I sold parts. One day I say, 'I'm stupid. I'm sending parts to manufacturers. Why don't I industrialize this?”

As he lowered costs, he saw the margins of his distributors increase. “My heart was crying, to see that.”

This led to his first major strategic insight: he needed to cut out the middlemen. All of them. He started by buying out most of his distributors or taking stakes in them.

This led to his first major strategic insight: he needed to cut out the middlemen. All of them. He started by buying out most of his distributors or taking stakes in them.

His second innovation was to combine his business with the fashion industry. In 1988, he signed his first licensing deal with Giorgio Armani. Thanks to the power of fashion brands, his glasses would become more desirable - and more expensive.

In 1990, he pulled off an IPO in New York. This gave him capital for a major deal. In 1995, he acquired United States Shoe. Wait, what? He expanded into shoes? Not quite.

The company owned the LensCrafters chain.

The company owned the LensCrafters chain.

Luxottica’s midrange was being squeezed by growing retail chains, lower healthcare reimbursements, and discount frames. After selling all other business units, he was left with LensCrafters at 1x revenue and 9x operating income. “The trick was keeping margins in-house”

Next came the $640mm purchase of Ray Ban from Bausch & Lomb in 1999. The brand was tired, “they were selling Wayfarers at Walmart.”

He upgraded quality, shifted production to Luxottica plants, and cut distribution channels. Today, Ray Ban is the company’s most valuable brand.

He upgraded quality, shifted production to Luxottica plants, and cut distribution channels. Today, Ray Ban is the company’s most valuable brand.

He bought Sunglass Hut in 2001. With growing scale, he could squeeze competitors.

“When they buy a company, they spend a little time figuring it out and kick out all the other suppliers.”

He asked for price cuts from all of Sunglass Hut’s suppliers. Only one refused: Oakley.

“When they buy a company, they spend a little time figuring it out and kick out all the other suppliers.”

He asked for price cuts from all of Sunglass Hut’s suppliers. Only one refused: Oakley.

Oakley’s founder Jim Jannard traveled to Italy to negotiate. When he left, Del Vecchio reportedly told him "we will never be friends."

Oakly supplied 25% of Sunglass Hut’s products and Del Vecchio started removing them from the shelves. Oakley’s stock dropped 37%.

Oakly supplied 25% of Sunglass Hut’s products and Del Vecchio started removing them from the shelves. Oakley’s stock dropped 37%.

“There was a kind of war going on.” Oakley sued and the case was settled.

In 2007, Luxottica bought Oakley for $2bn

In 2007, Luxottica bought Oakley for $2bn

Del Vecchio had retired in 2004 but returned in 2014 at age 79. He orchestrated the €48bn merger with the French leader in lenses: Essilor.

Essilor’s history dates back to 1849 as a worker’s cooperative. In 1959 it introduced Varilux, the first progressive lenses.

Essilor’s history dates back to 1849 as a worker’s cooperative. In 1959 it introduced Varilux, the first progressive lenses.

This deal was the final piece of vertical integration: one global company supplying frames and lenses, present at every step of the value chain.

Today, Del Vecchio remains chairman. He and his family are worth an estimated $26 billion.

In addition, more than 60,000 employees are shareholders.

In addition, more than 60,000 employees are shareholders.

There is of course controversy around the company’s power and opaque pricing of prescription eyewear:

“There is no competition in the industry. Luxottica bought everyone. They set whatever prices they please.”

latimes.com/business/lazar…

“There is no competition in the industry. Luxottica bought everyone. They set whatever prices they please.”

latimes.com/business/lazar…

Follow me and subscribe to my substack if you’re interested in more stories and lessons from legends in business and investing.

neckar.substack.com

neckar.substack.com

Playing monopoly with your billionaire dad:

"He won easily and told us why: 'When you've got land, you shouldn't build little houses on it right away. First you have to keep a close eye on your capital and not spread it around wildly."

"He won easily and told us why: 'When you've got land, you shouldn't build little houses on it right away. First you have to keep a close eye on your capital and not spread it around wildly."

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh