On Friday, I will lead a discussion on histories of land tenure & political violence in Kenya & Ethiopia. To frame the conversation, we will think alongside @NgugiWaThiongo_'s Weep Not, Child & @HaileGerima's Harvest, 3000 Years. Both of these powerful pieces raise 1/

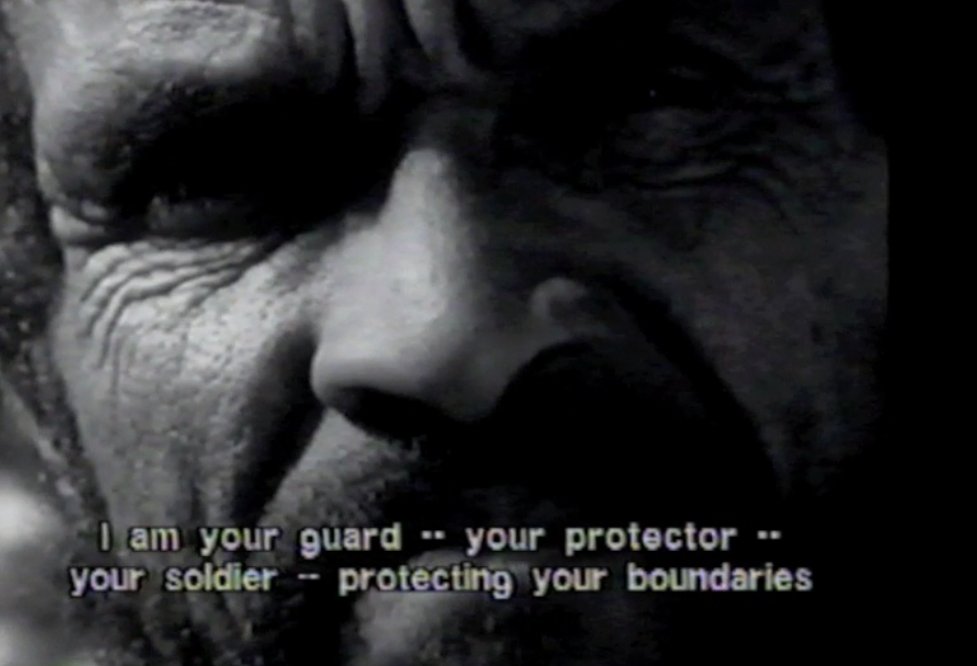

penetrating questions—some similar, others not—re: labour, class & racial exploitation, gender, family debates, resistance, & historical imagination. As @ElleniZeleke reminds us, Gerima's later films, Imperfect Journey & Teza, question revolutionary violence surrounding 1974. 2/

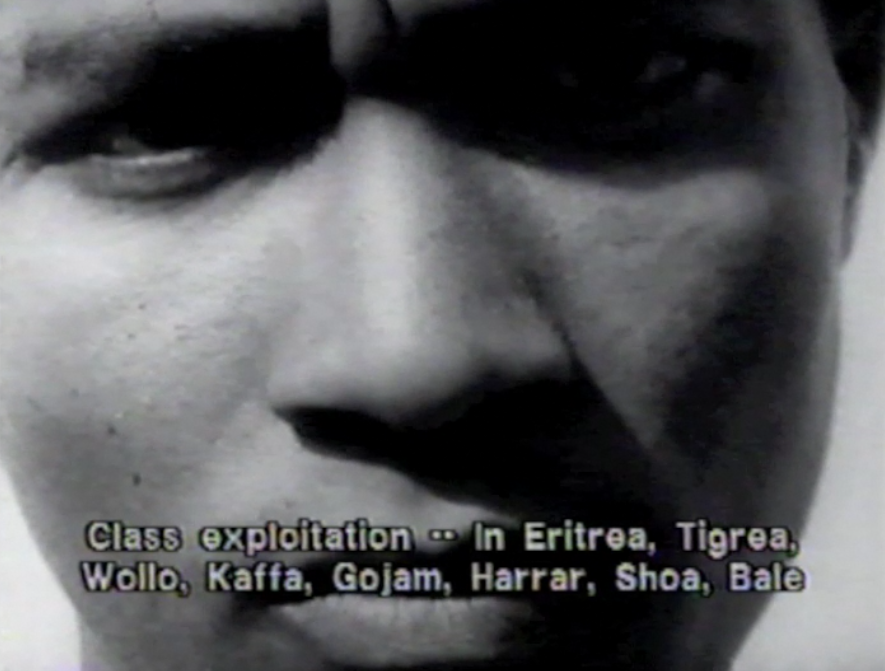

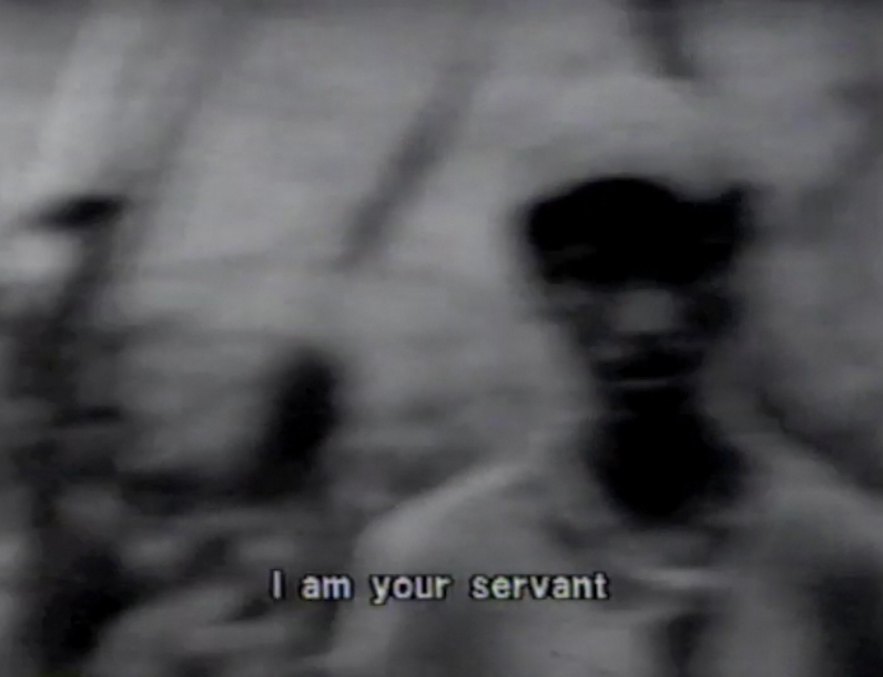

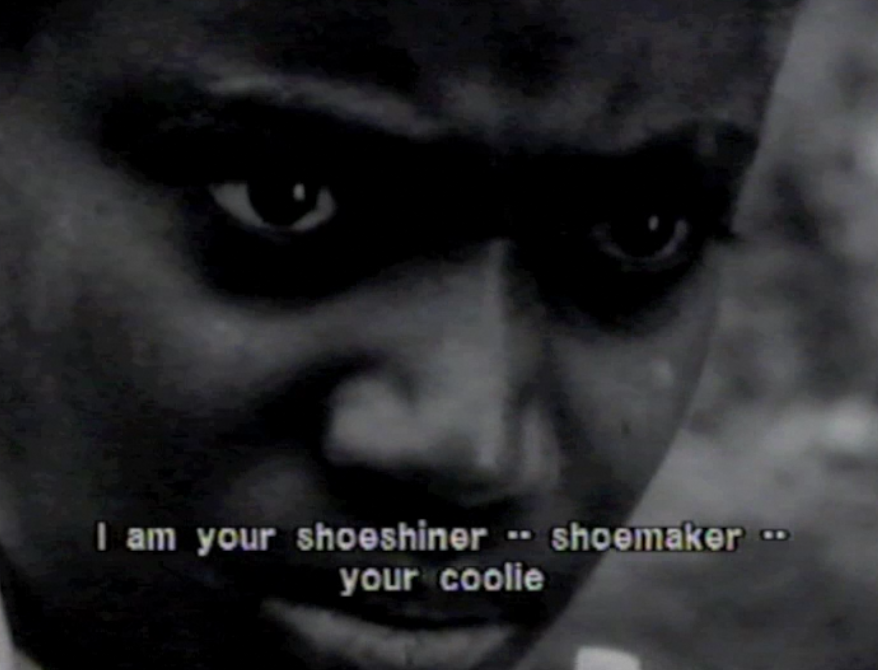

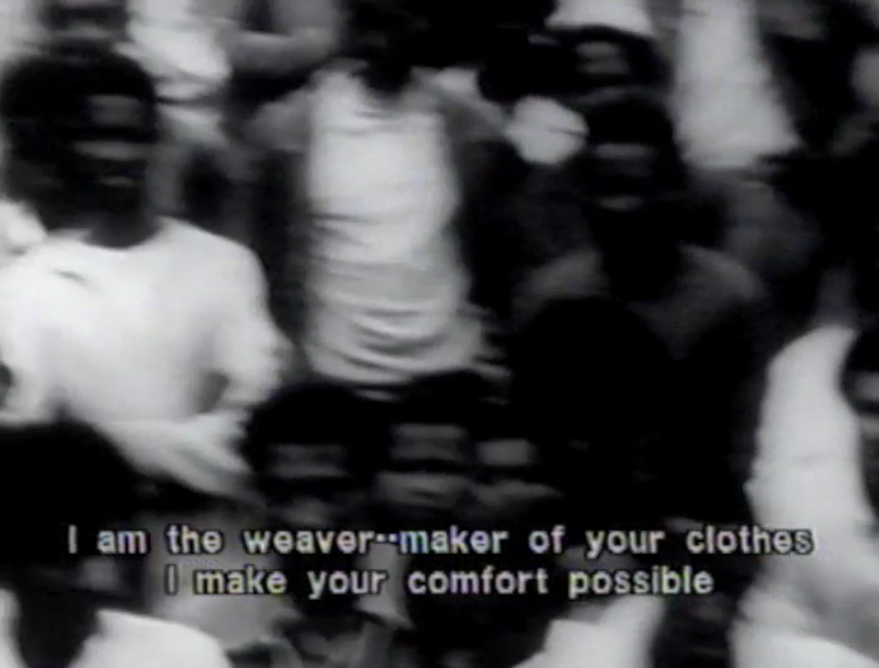

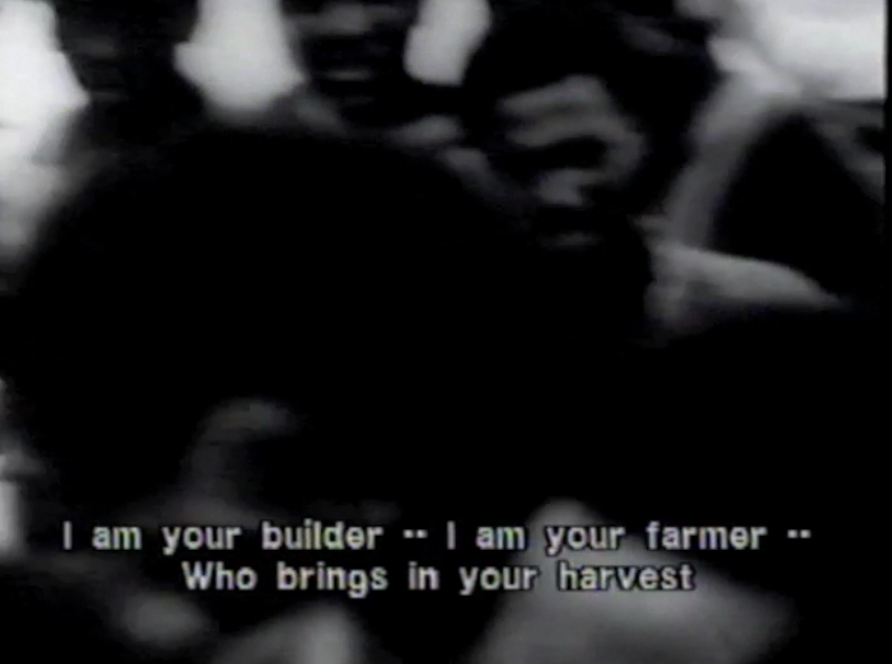

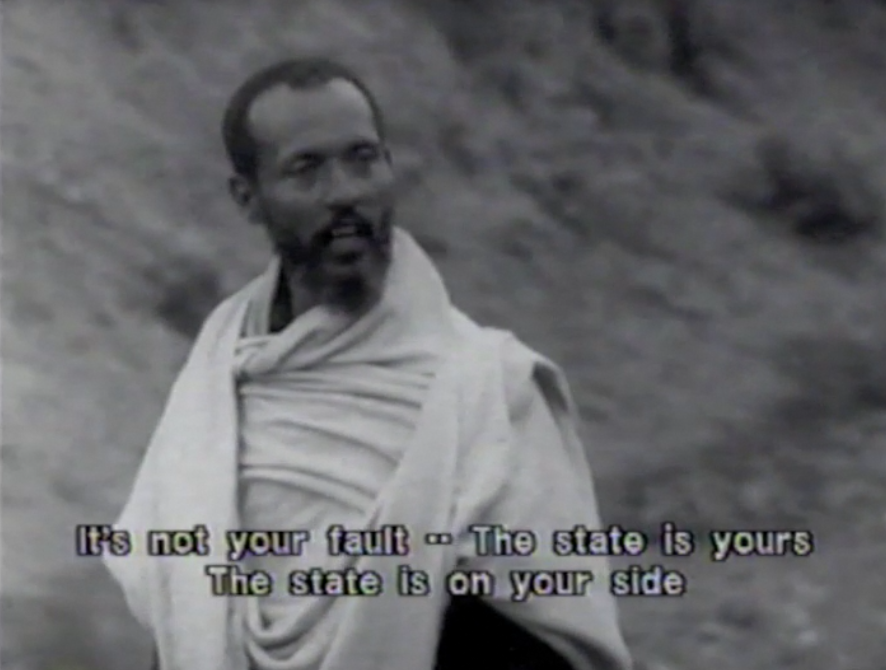

Harvest, by contrast, was produced much earlier: in 1976. It critiques land tenure & labour in Ethiopia while showing how one emerging regime of exploitative power was now replacing one whose genealogy was birthed on the bed of Solomon. 3/

One is instantly reminded of the opening sentences of the Manifesto of the Communist Party: 'The modern bourgeois society that has sprouted from the ruins of feudal society has not done away with class antagonisms. 4/

It has but established new classes, new conditions of oppression, new forms of struggle in place of the old ones.' One regime of exploitation has replaced another. In between the 2 are ordinary lives and communities struggling for justice and reform. 5/

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh